Dogs, our oldest animal companions, have walked beside humans for tens of thousands of years. But how did this ancient partnership begin? For decades, scientists have debated whether humans actively tamed wolves through selective breeding or whether some wolves self-domesticated by scavenging near human settlements, leading to a gradual shift in temperament and behavior. One of the biggest challenges to the second idea—often called the proto-domestication hypothesis—has been time. Could natural selection alone turn wolves into early dogs quickly enough to match the archaeological record?

A new study published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B tackles this question using agent-based modeling, a powerful simulation technique used in ecology and evolutionary biology. Led by David Elzinga and colleagues from multiple universities, the research suggests that, under the right conditions, wolves could have evolved into dogs much faster than previously thought—possibly within just 8,000 years. If correct, this finding challenges the long-held assumption that deliberate human intervention was necessary for the emergence of early dogs.

“Our results indicate that the proto-domestication hypothesis cannot be rejected on the basis of time constraints.” —Elzinga et al., 2025

This is not just a mathematical curiosity—it reframes our understanding of the deep evolutionary relationship between humans and canines.

Instead of analyzing fossils or DNA, Elzinga and his team turned to computational modeling to simulate how wolves might have become dogs over 15,000 years. Their agent-based model (ABM) functioned as a virtual ecosystem populated by individual wolves, each with distinct traits such as human tolerance, mating preferences, and hunting strategies. By tweaking different evolutionary pressures—such as access to human food scraps and mate selection based on tameness—the researchers could observe how different factors influenced the likelihood of wolves evolving into dogs.

The model produced striking results:

-

In 37–74% of simulations, wolves evolved into dogs within a time-frame consistent with archaeological evidence.

-

Sexual selection (where wolves preferentially mated with others who were more tolerant of humans) played a crucial role in accelerating domestication.

-

The presence of human food sources influenced which wolves survived, favoring those that could tolerate humans.

-

Even in the absence of human-controlled breeding, the conditions of early human settlements provided a selective pressure that could drive rapid evolutionary change.

“A striking result from our study was the necessity that the mate preference routine be employed to witness divergence of the canine populations according to human tolerance values.”

In other words, without sexual selection—where tamer wolves mated more frequently with each other—the transformation into early dogs was far less likely to happen within a short time period.

One of the biggest objections to the proto-domestication hypothesis is whether early human settlements produced enough leftover food to support a scavenger population of wolves. Some researchers have argued that Paleolithic hunter-gatherers simply wouldn’t have had enough surplus food to sustain a population of evolving proto-dogs.

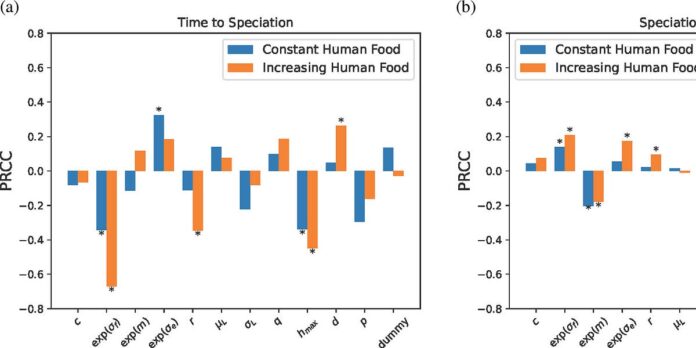

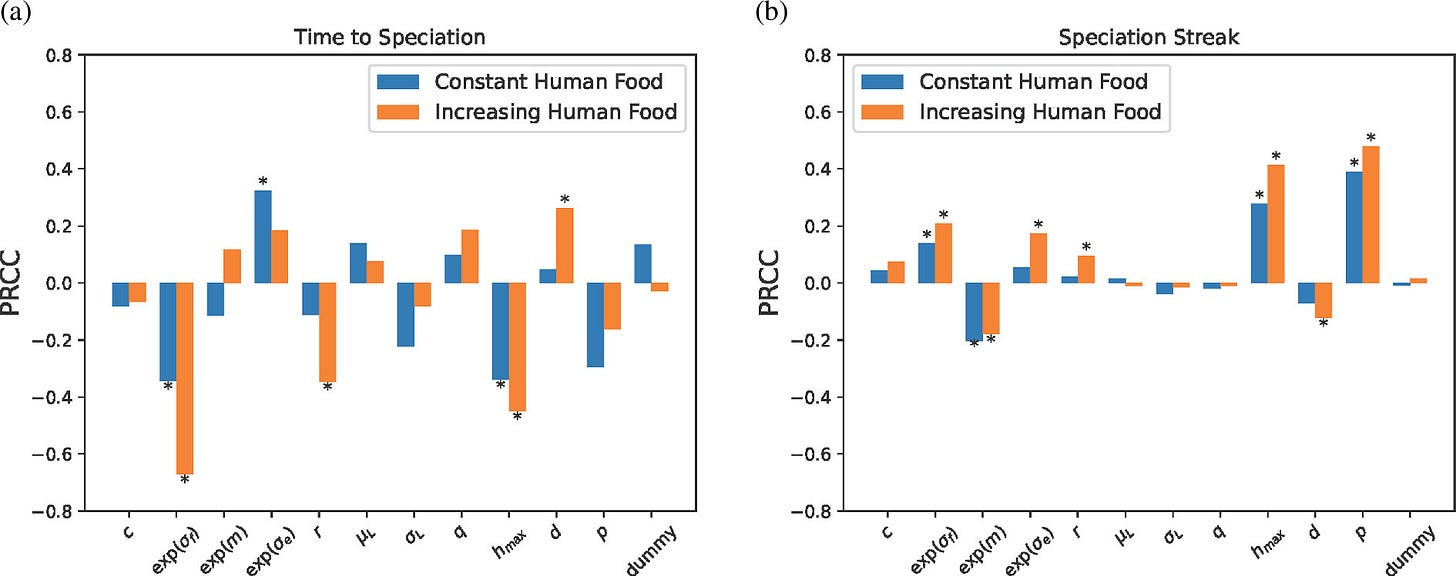

Elzinga’s model indirectly addresses this concern by showing that even modest amounts of human-associated food could shift the evolutionary trajectory of wolves. Interestingly, their results suggested that environments with fluctuating food availability made speciation— the emergence of a separate dog-like population—more likely.

This raises a provocative possibility: Instead of a slow, gradual shift, dog domestication may have happened in bursts, triggered by environmental changes or shifts in human behavior.

“Our sensitivity analysis suggests that the volume of human food is one of the most important parameters in dictating the amount, speed, and robustness of speciation.”

If Elzinga’s findings hold up, they challenge the long-standing assumption that early humans played an active, deliberate role in domesticating wolves. Instead, it suggests that wolves may have domesticated themselves by adapting to human presence.

This idea isn’t entirely new. It aligns with a famous experiment on silver foxes conducted by Russian geneticist Dmitry Belyaev in the mid-20th century, which showed that selecting for tameness alone could lead to rapid changes in morphology and behavior, such as floppy ears, shorter snouts, and a greater tendency to seek human interaction. Elzinga’s model suggests that a similar process could have unfolded naturally in prehistoric wolves—without human interference.

This also raises fascinating questions about other domesticated species. If self-domestication was possible for wolves, could it have played a role in the domestication of other animals, like cats or even early livestock? And, on a more speculative level, could certain aspects of human social evolution have followed similar principles?

“If this preference existed among the ancient wolf population, it implies that human tolerance could be a ‘magic trait’ in that it contributed both to ecological selection and to non-random mating.”

This notion of a “magic trait”—one that influences both survival and reproductive choices—may be crucial to understanding why wolves were domesticated, while other large carnivores, such as hyenas or foxes, were not.

Despite its compelling conclusions, Elzinga’s study is not without limitations. As a mathematical model, it does not provide direct archaeological or genetic evidence—it simply demonstrates that a particular evolutionary pathway is plausible. Further research, particularly genetic analysis of ancient dog remains, will be necessary to test whether the patterns predicted by the model align with real-world data.

Another unresolved question is whether wolves in different parts of the world followed the same domestication path. Genetic evidence suggests that dog domestication occurred in multiple regions over tens of thousands of years, and it’s possible that different populations of wolves were domesticated under different evolutionary pressures.

Nonetheless, this study provides a fresh perspective on an age-old mystery. Rather than viewing domestication as a purely human-driven process, it suggests that some of our closest animal companions may have played a more active role in their own evolutionary story.

“Our results cannot prove nor disprove the cause of early wolf domestication. Yet, assuming mate preference, 74.2% of repetitions resulted in speciation at default parameters, while 6.7% of repetitions resulted in speciation across all parameter combinations during the sensitivity analysis. This quantitatively confirms the proto-domestication hypothesis cannot be rejected due to time constraints alone.”

The wolves that became dogs may have chosen to live alongside us—not because we tamed them, but because they evolved to see us as their best chance for survival.

For further reading on dog domestication and evolutionary modeling:

-

Bergström, A. et al. (2022). “Grey wolf genomic history reveals a dual ancestry of dogs.” Nature, 607, 313–320. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-04824-9

-

Germonpré, M. et al. (2009). “Fossil dogs and wolves from Palaeolithic sites in Belgium, the Ukraine and Russia: osteometry, ancient DNA and stable isotopes.” Journal of Archaeological Science, 36, 473–490. DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2008.09.033

-

Savolainen, P. et al. (2002). “Genetic evidence for an East Asian origin of domestic dogs.” Science, 298, 1610–1613. DOI: 10.1126/science.1073906