Did the Grand Canyon Lodge burn because the Grand Canyon lacked hungry herbivores?

GRAND CANYON, Arizona––A well-placed and well-timed bucket of water or the sudden, unexpected arrival of Smokey Bear, with or without hat and shovel, can stop a wildfire before it gets started.

Likely neither a bucket of water nor a bear directed at either side of the argument can settle––or stop––heated debate each and every wildfire season throughout the western U.S. about whether either more or less wildlands grazing can help prevent fires now razing as much as 1,000% more forest per year than forty years ago.

The Dragon Bravo fire

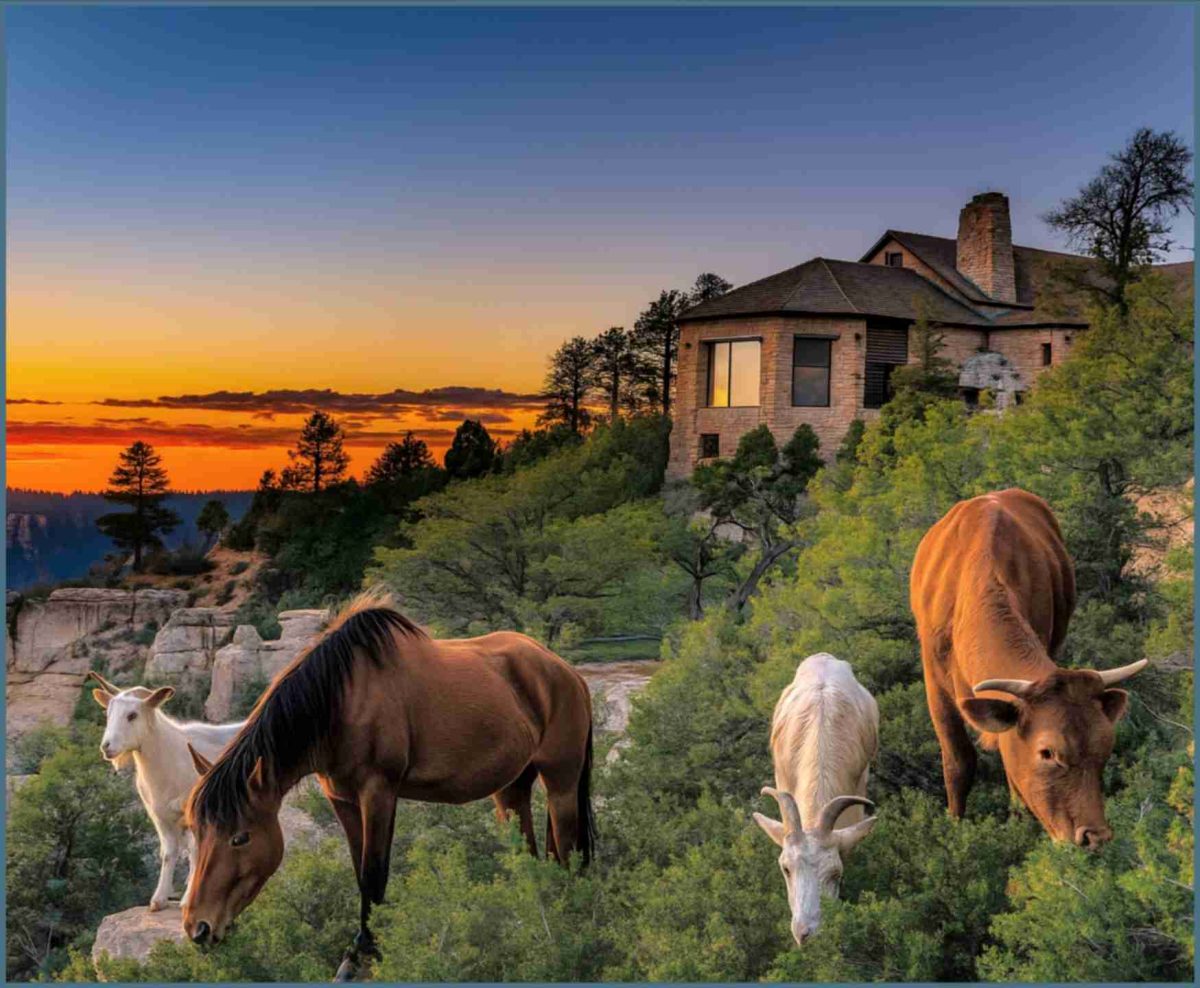

The latest nationally noted spark to the argument, as of mid-July 2025, was the destruction of the Grand Canyon Lodge on the North Rim of the canyon, engulfed and razed on July 12-13, 2025 along with the visitor center, the gas station, a waste water treatment plant, an administrative building and some employee housing.

The Grand Canyon Lodge was a casualty of the lightning-sparked 5,000-acre Dragon Bravo fire. The nearby White Sage fire meanwhile burned more than 40,000 acres.

The original Grand Canyon Lodge, built in 1928, burned in 1932, the Grand Canyon Historical Society reminded.

Rebuilt using the original stonework walls and foundation, the Grand Canyon Lodge familiar to living visitors opened in 1937.

What to do about grasses & standing dead trees?

“On the southern edge of the fire, hand crews and bulldozers were working uphill, and the spread of the blaze had been minimal,” The Guardian reported.

“But to the east and north, the fire has spread rapidly, with grasses and standing dead trees contributing to the fire’s intensity, officials said.”

What to do about grasses and standing dead trees, many left from previous wildfires, is the crux of the strategic issue.

Loggers of course tend to favor salvaging the dead trees, to the extent that they can be salvaged. The chief opposition to that comes from bird conservationists arguing on behalf of the many avian species who make their nests in dead trees and hunt the insects, mostly beetles, who also colonize and partially consume dead trees.

Ranchers & goat-herders

Ranchers favor more cattle and sheep grazing, to eat down the grasses before they dry out and burn.

That perspective was amplified on June 6, 2025 by Colorado Sun reporter Tracy Ross, who credited “48 cow-calf pairs brought to the grassy meadow above the Shanahan Ridge neighborhood near the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder” with preventing repetition of wildfires that hit the Boulder region in March 2022.

Goat-herders have meanwhile discovered that leasing their herds to clear flammable roadside brush pays better than raising goats for milk, meat, and byproducts––which businesses can all be combined with brush-clearing.

This approach also tends to get favorable media notice, though the goats really only do the same thing as deer, albeit under human supervision to prevent roadkills.

Deer, elk, & pronghorn

Hunters tend to like the grazing approach to fire prevention, but also tend favor larger populations of deer, elk, and pronghorn over maintaining the presence of any species of domestic livestock.

Deer, elk, and pronghorn will eat down flammable grasses to some extent, but prefer the brushy growth that usually follows the grassland stage in post-fire habitat regeneration.

Allowing the brush to recover, succeeding grass, requires keeping livestock off the grass. This also allows second-growth forest to get started.

As the forest matures, the brush becomes understory, a favored nesting habitat for songbirds, but as tree canopy recovers, much of the understory is shaded out, dies, and becomes the tinder for the next wildfire.

Typically a small grassfire will ignite a larger brushfire, which will in turn generate the heat necessary to cause trees to flash over into a forest fire.

“Wild Horse Fire Brigade”

Some wild horse advocates, led by “Wild Horse Fire Brigade” proponent William E. Simpson II, argue that many or even all of the estimated 62,000 wild horses now in Bureau of Land Management holding facilities, after being removed from overgrazed range chiefly in Nevada and Wyoming, should be released elsewhere in “critical wilderness areas” to join deer, elk, and pronghorn in keeping down grass and understory.

Simpson credits wild horses on his own land in Siskiyou County, northern California, with creating and maintaining the conditions that have kept nearby wildfires from spreading into the area.

“Aggregate of herbivores”

Simpson acknowledges that, “The aggregate of herbivores in Nevada,” including “deer, elk, horses, cows, sheep, rabbits and herbaceous insects,” is causing “over-grazing issues.

“Humanely removing and relocating most of the wild horses from Nevada, and redeploying––re-wilding–– them as families into the remote vacant lands of the far western states, California and Oregon, that are plagued by massive wildfires fueled by grass & brush is a smart, cost-effective move,” Simpson argues.

“These lands, tens of millions of acres, are not suited for any commercial livestock production. However, such lands are ideal for American wild horses, where they can live-naturally and in the process, manage grass and brush wildfire fuels.”

Hunters vs. wild horses

That sounds good to wild horse advocates, especially in view of Donald Trump administration hostility toward continuing to spend upward of $135 million a year to feed impounded wild horses.

The pro-hunting, pro-grazing Coalition for Nevada’s Wildlife, including 120 partner organizations, on June 15, 2025 asked Congress and Trump administration officials to again allow unlimited sales of wild horses and burros, including to slaughter or, since there currently are no USDA-inspected slaughterhouses killing horses for human consumption, bunchers delivering horses to slaughter for the horsemeat export industries in Mexico or Canada.

Over-hunting & habitat change

Among the signatories was Backcountry Hunters & Anglers, a Wyoming-based group with reportedly considerable clout within the Trump cabinet, and considerable anxiety, as well, about populations of mule deer declining chiefly in recent decades through the combination of habitat altered by climate change with over-hunting.

“Over-hunting,” in the context of diminished carrying capacity, can mean simply continuing to allow hunting at levels that were sustainable just a few decades ago.

Acknowledging the effects of climate change, meanwhile, would contradict one of the focal positions of the Trump regime.

Wild horse roundups resume

Jenny Lesieutre, Bureau of Land Management “state lead for the Wyoming wild horse and burro program before becoming the agency’s wild horse and burro public affairs specialist in Nevada,” according to Cowboy State Daily reporter Mark Heinz, retired in July 2024, but as of July 13, 2025 was on the stump for reducing the U.S. wild horse and burro population to just 25,556.

This would include 2,566 wild horses and burros in Wyoming and 12,811 in Nevada, where there are now as many as 8,706 and 51,525, respectively.

These would be approximately the same numbers of wild horses and burros as existed at the time of the 1971 passage of the Wild Free-Roaming Horses & Burros Act, establishing the present management regime.

Coincidentally, the Bureau of Land Management on July 15, 2025 began rounding up for removal 3,000 wild horses from the Great Divide Basin, Salt Wells Creek, and Adobe Town herd management areas in Wyoming.

Wild horses in Congress

Pointed out Humane World for Animals president Kitty Block in her Humane World blog post of June 4, 2024, “The White House’s Fiscal Year 2026 budget request attempted to remove longstanding protective language that prohibits the outright killing or sale for slaughter of wild horses and burros.

“It is particularly chilling,” Block wrote, “that the Project 2025 Mandate for Leadership document included a call for allowing the Bureau of Land Management to ‘dispose’ of wild horses and burros because they pose an ‘existential threat’ to public lands.”

The Animal Welfare Institute, American Wild Horse Conservation, and Return to Freedom on July 14-15 2025 rejoiced that the U.S. House Committee on Appropriations included language in its fiscal year 2026 Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies funding bill that “prohibits slaughter, rejects mass equine transfers to foreign governments, and affirms congressional oversight of the BLM’s Wild Horse & Burro Program,” AWI and AWHC spokespersons Marjorie Fishman and Amelia Perrin summarized.

But all three organizations warned that the House Committee on Appropriations recommendations must still be ratified by the House of Representatives as a whole, the U.S. Senate, and the final budget reconciliation process.

No such thing as fireproof prime wildlife habitat

Meanwhile, whether more wild horses than are already present would be compatible with the other wildlife in “critical wilderness areas,” as Simpson suggests, is at best questionable.

The real problem is not the question of “native” versus “non-native,” nor of “wild” versus domestic.

Rather, it is that all stages in the growth of either grazing land or “critical wilderness areas” coincide with both the habitat needs of some keystone species and endangered species, and with certain types of elevated fire risk, depending on weather and climate.

There is no such thing as fireproof prime wildlife habitat. Wildlife and habitat have evolved with fire. Many plants actually need fire for their seeds to germinate and reproduce. Many animals make extensive use of post-wildfire conditions.

(See Cold Canyon Fire Journals speak to war, global warming, resilience of life.)

The four stages of wildfire

Finally, effective fire prevention requires recognizing the four stages of wildfire, as outlined by the Western Fire Chiefs Association: incipient, also known as ignition; growth; fully developed; and decay.

According to the Western Fire Chiefs Association, “A fire is at the incipient stage when it has small flames and low heat,” like a grassfire beginning from the reflection off a broken bottle magnifying sunlight at a roadside, or ignited by blowing sparks from an overheated freight train brake box, or by a carelessly tossed cigarette butt.

Such a grassfire can start even when intensive grazing has nibbled the grass down to almost nothing. Whether it spreads depends not only on the availability of fuel––which of course is a must––but also on the wind. Strong winds will blow sparks farther and faster, to ignite taller grass farther away.

From brushfires to flashover

Continues the Western Fire Chiefs Association, “A fire enters the growth stage as it continues to burn. Spreading brushfires are an example of this,” as initially small grassfires burn into understory, and then into tree cover, leaping into canopy to blow from tree to tree.

“The fire’s heat at the growth phase can ignite everything combustible,” the Western Fire Chief’s Association says, “including smoke from the fire itself. This is called flashover, when temperatures can rise to 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit in seconds.

“After flashover occurs,” the Western Fire Chiefs Association explains, “the fire is in the fully developed stage when the temperature reaches its highest point, sometimes almost 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit. These are dangerous wildfires that spread rapidly and can consume trees and huge areas of forest and grassland.

“A fully developed wildfire will continue to burn until it runs out of fuel.”

The longest stage of a fire

But just running out of fuel in the immediate vicinity of a wildfire does not end the risk that it will spread or reignite.

“The final phase of fire growth is the decay stage,” the Western Fire Chiefs Association concludes. “This is often the longest stage of a fire, as the flames decrease in size and the heat of the fire begins to drop.

“A wildfire that is decreasing in size and running out of combustible material,” the Western Fire Chiefs Association warns, “is in the decay stage, but the fire can still be dangerous. A fire can restart if there is still fuel to burn and if winds pick up to add more oxygen to the fire.”

Pounding hoofs

No one grazing or browsing species, present in sustainable numbers, can really prevent or suppress all wildfires. Some keep down grass, some keep down understory, and some do both, but whatever a grazing or browsing animal eats, and tramples, there has to be enough of it to keep the animal well-fed enough to stay.

If the flammable vegetation is all consumed, the species will depart for greener pastures, or forests, leaving the vegetation to grow back––unless, of course, the habitat has become desert due to overgrazing and soil erosion typically caused in large part by pounding hoofs.

The animal most useful in wildfire prevention

The bottom line in any and all arguments for increasing populations of grazing or browsing species to fight wildfire tends to be a pretext for keeping whichever species the person or group doing the arguing favors, whether for economic or aesthetic reasons.

The one animal whose presence always inhibits wildfires is the beaver.

Beavers gnaw down dead trees, if they still have bark, using the wood to build dams that create ponds which in turn become barriers to wildfire, and even store water useful in fighting wildfires.

Please donate to support our work:

More related posts:

Discover more from Animals 24-7

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.