When immigration agents accosted Mahmoud Khalil and his wife in the lobby of their apartment building in New York City in early March, the Palestinian solidarity activist, former Columbia University graduate student, and expecting father became the symbolic target of the Trump Administration’s crusade to expel noncitizen activists who have participated in nationwide campus protests against Israel’s genocide in Gaza. Yet Khalil’s detention in Louisiana and pending deportation reflect a history of politicized immigration enforcement that extends far beyond the political maelstrom around Palestine.

In some ways, Khalil’s case seems exceptional: The removal of legal permanent residents is relatively rare, especially as Khalil has not been convicted of any crime. His main offense, according to the Department of Homeland Security, is engaging in “activities aligned to Hamas”—the administration’s shorthand for peaceful pro-Palestine protests. Although he has been spared deportation while his case is pending in immigration court, his detention—coupled with Donald Trump’s threat to slash federal funding for any school or university that allows “illegal protests”—reveals that this administration is focused on targeting anyone deemed politically undesirable, even if they are a legal permanent resident.

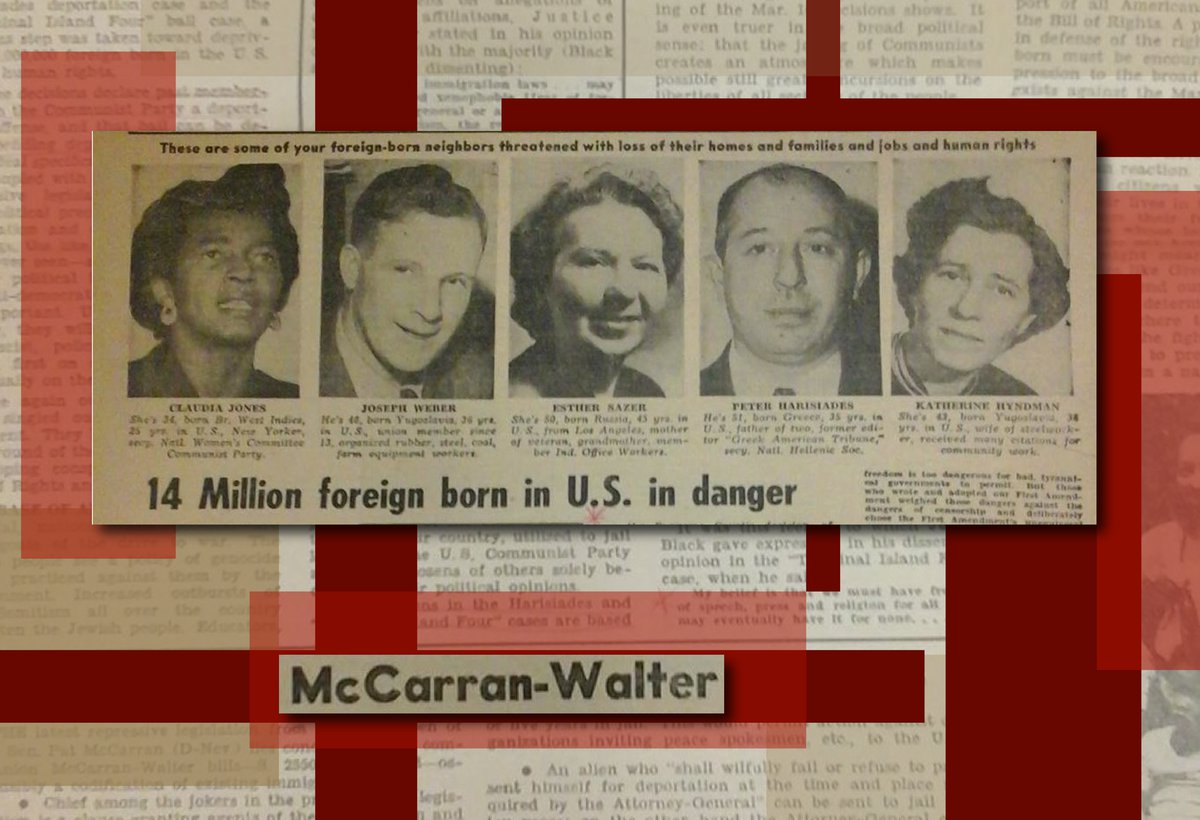

Yet Khalil’s case is not so unique. First, he is one of several academics who have been threatened with deportation in recent months in the backlash to the pro-Palestine protests. Days after his arrest, the Trump Administration revoked the visa of another Columbia graduate student who participated in last year’s protests. Khalil’s case also folds into a long history of the U.S. government wielding political deportation as a tool of repression. Secretary of State Marco Rubio claims he is deportable under an arcane provision of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, also known as the McCarran-Walter Act, a product of Cold War anticommunist hysteria, which states that a noncitizen can be deported if the Secretary of State believes their “presence or activities in the United States . . . would have potentially serious adverse foreign policy consequences for the United States.” In publicly demonizing human rights activists like Khalil as violent extremists, the White House draws on the ideological mythmaking of the 1950s Red Scare.

Seventy-five years before Khalil was shunted into a detention center in Jena, Louisiana, Black Trinidadian-born Communist Party leader Claudia Jones looked out over New York harbor from the prison at Ellis Island, where she was imprisoned in 1950, awaiting deportation. Jones, whose blend of Marxist feminism and militant racial justice activism had made her a target of the federal government for years, wrote a letter in 1950 contemplating her experience as a radical en route to exile, observing that the Statue of Liberty “literally stands with her back to Ellis Island.”

Jones mused that America’s global image as a beacon of freedom and refuge for immigrants was betrayed by the way the country treated immigrant activists like her. She, like many other political activists, had been denied bail under the 1950 Internal Security Act, which gave the President “emergency” powers to use preventive detention against someone suspected of espionage or sabotage. For Jones and her fellow detainees, including trade unionists and civil rights activists, deportation—which is a matter of civil, not criminal, law—had become a weapon of persecution that felt utterly disconnected from the United States’s reputation as the world’s preeminent democracy.

“The ridiculous part of it,” Jones wrote, “is that the American people are supposedly asked to believe that we are ‘awaiting deportation hearings’—a ‘normal procedure.’ ” She continued, “The truth, of course, is that this is a clear violation of the American Constitution [and] the Bill of Rights, both of which guarantee the right of bail and the right of habeas corpus.”

Around the same time, Harry Carlisle, a British-born writer and founding member of the Los Angeles Committee for the Protection of Foreign Born, was penning his own observations from the Terminal Island detention facility near Los Angeles, an immigration prison off the coast of California. Carlisle was being held with three other noncitizen leftists who alongside him became known as the Terminal Island Four: Korean-born architect David Hyun, Polish-born communist educator Frank Carlson, and British dance instructor Miriam Stevenson. Comparing the the unilateral and undemocratic authority with which the state had detained him to the allegations against Carlisle and his fellow immigrants, he wrote in an open letter to then Attorney General Howard McGrath:

“Your department terms us ‘undesirable.’ Yet all four of us have been residents of the United States or its territories for decades, some of us since early childhood, and we have no criminal records. . . . Yes, we are part of the millions of foreign-born non-citizens, whom you now threaten with jail and deportation in order to coerce them into compliance with beliefs and policies leading to war and fascism.”

While it was framed as an immigration reform law, McCarran-Walter actually built on a series of national security policies clamping down on leftwing political activity in the preceding years. There was the 1940 Alien Registration Act, which required immigrants to register with federal authorities and criminalized any movement or organization deemed to be advocating the “overthrow” of the government. A decade later came the Internal Security Act of 1950, which established a Subversive Activities Control Board to surveil and suppress leftist organizations and gave the President emergency powers to detain those suspected of espionage or sabotage.

McCarran-Walter also maintained draconian immigration restrictions that had sharply limited migration from Eastern and Southern Europe, while imposing political strictures targeting the left. In turn, foreign-born Americans, even naturalized citizens, who had been involved with labor and political activism since the Popular Front mobilizations of the 1930s, became more vulnerable to being investigated, detained, and removed from the country on political grounds. Some immigrants were surveilled and put into deportation proceedings based on evidence of “subversive activity” that dated back decades.

According to a survey by the National Lawyers Guild published in 1955 of more than 200 people arrested for deportation on political grounds between 1944 and 1952, nearly all had resided in the United States for at least twenty-one years; two out of three had lived in the United States for more than thirty-one years. A large majority were also more than sixty-five years old. Nearly half hailed from Eastern Europe or the Balkans. Nearly half had applied for citizenship at least once, and a similar portion were parents of children who were U.S. citizens. About one in ten had been officers of trade unions, underscoring how being a visible labor activist could expose one to political persecution via immigration enforcement.

James Matles, the Romanian-born director of organization for the leftwing United Electrical Workers Union (UE), faced denaturalization based on allegations that he had been a communist prior to becoming a citizen. A pamphlet issued by UE described Matles as a victim of both the state and the corporations he had challenged as an organizer, like Westinghouse and General Electric, noting that the Justice Department had previously attempted to indict him under the anti-communist provisions of the conservative Taft-Hartley labor law. “If the corporations succeed in taking away his citizenship because of his effectiveness as a labor leader,” the pamphlet read, “Matles and his American-born wife and child won’t be the only ones hurt in the process . . . . Foreign-born workers, whether non-citizens, naturalized, or first-generation, would see this as a threat to their own [status] if they stand up to rate-cuts, speed up, and seniority violations. It would disorganize electrical and machine workers.” (Matles ultimately took his fight to retain his citizenship to the Supreme Court, which threw out the case in 1958.)

The zeal for political deportation faded largely by the early 1960s. The McCarthyite climate of repression had dissipated due to political backlash and courts invalidating some of the most draconian anti-communist restrictions. But the intersection of political persecution and immigration enforcement has resurfaced in more subtle ways in recent years.

In 2018, Ravi Ragbir, a Trinidadian-born immigrant rights advocate who had been a prominent deportation defense advocate with the New Sanctuary Project in New York City, was abruptly detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) on a long-pending deportation order. He claimed in court that ICE was punishing him for his activism, violating his First Amendment rights.

Another chilling precursor to Khalil’s experience was the case of the 1987 Los Angeles Eight, in which a group of young activists in California—seven Palestinians and one Kenyan—were charged with being members of the Marxist-Leninist Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. Years later, with the passage of the post-9/11 USA PATRIOT Act, the government doubled down by additionally charging Los Angeles Eight members Khader Hamide and Michel Shehadeh, both green card holders, with giving “material support” to a terrorist organization. The case was finally dismissed twenty years later, after the government failed to present evidence of their membership in the named organization. By then, the activists had settled into fairly ordinary lives as naturalized citizens and permanent residents of the United States.

Hopefully, Khalil and his young family will not have to wait another twenty years for justice. But their allies, in rallying to demand his release, are already writing the next chapter in an old story of political deportation and resistance.

In 1953, Abner Green, the leader of the American Committee for the Protection of Foreign Born, reported growing concern that foreign-born U.S. residents faced unprecedented threats amid the nationwide rise of anti-communist and anti-immigrant sentiment, ongoing conflict with Communist China in the Korean War, and an intensifying atmosphere of repression. But so, too, did all other Americans.

“Congress is anti-alien. The Justice Department is anti-alien. The courts are anti-alien,” Green warned at a national conference for immigration advocates. The group, he argued, would have to defend equal justice for immigrants by centering universal values enshrined in the Bill of Rights, for U.S.- and foreign-born people alike. “We have one advantage,” he said. “We speak of and for the people of this country. We are with the millions of Americans who want peace and who want security. To them we say the deportation of non-citizens is part of this attempt to destroy the liberties of the American people, to impose police-state conditions of living for all persons in the country in order to prevent a united people’s fight for peace.”

The committee’s movement defended noncitizens’ rights under the banner of defending all Americans’ right to due process and dignity. In many cases, they were successful—of those investigated and ordered deported, only a small percentage were actually removed, thanks to a robust legal defense from civil liberties advocates, and courts that were at least somewhat sympathetic to their free speech arguments. In the National Lawyers Guild study, only about five percent of the cases studied ended with an actual removal. The main hardship most of the targeted dissenters endured was not expulsion itself, but the burden of detention, surveillance, and protracted legal limbo.

Nonetheless, the failure of the government’s postwar deportation drive suggests that a fierce defense of the First Amendment and due process rights for noncitizens helped many activists and their families avoid the worst of the xenophobic political persecution under McCarthyism.

As Claudia Jones put it in her 1950 letter, deportation resistance is not about what happens in the courts. “Legal struggles, important as they are . . . are incidental to the mass struggle to free us . . . . No law or decree can whittle away or pierce by one iota our convictions and loyalty to America’s democratic and revolutionary traditions.” She continued, “What we want is aid—aid morally, financially, and above all by mass protests and action, to the mass campaign of the American Committee for Protection of the Foreign Born, by the trade unions, the Negro people, the women, the youth, national groups, and all labor progressives who love peace and cherish freedom, lest all face the bestiality and tormented degradation of fascism.”

A new mass struggle may now be emerging once again to defend politically persecuted immigrants. We are seeing the beginnings of it in recent demonstrations in New York City, with Columbia activists calling for Khalil’s release and Jewish protesters declaring “Not in our name.” A few months ago, Khalil himself was protesting alongside them, calling for peace and Palestinian freedom. Now, the activist has written from detention, like many before him, declaring, “At stake are not just our voices, but the fundamental civil liberties of all.” His own freedom will rely on his allies taking up the struggle where he left off, demanding justice everywhere, without borders.