The

opening of 2020 has been unusual. Bushfires have been roaring in Australia for

months. A weird flu season has caused thousands of lives in the U.S. Locusts in

swarms have been tearing across East Africa. And in China, an epidemic brought

by an infectious virus has been shaking the state’s foundation of governance that

is already in crisis.

Officially

referred to as COVID-19, the outbreak of the new coronavirus disease is now

devastating the country. A Chinese doctor, Li Wenliang, who was among the

earliest to warn his colleagues and friends of a “SARS-like virus,” got

infected and died on the night of February 6, 2020. Li was hailed a hero for

his action to call attention to the outbreak of COVID-19, which led him to be reprimanded

by the local police and called as a “rumormonger” in the early days of the

epidemic. As the disease has taken the country by storm, the authorities were

slapped on the face for their initial handling of the “rumors” about the virus,

clearly and painfully reminiscent of the lack of openness during the SARS

outbreak in 2003. As the new epidemic took off in 2020, the level of openness

and information sharing is largely increasing, but so does the censorship and

surveillance, which humiliate the intelligence of millions of Chinese in the

authorities’ clumsy attempt to control Li’s death narrative.

News

of Li’s death started to spread on social media and reported by some news media

in China, on the night of February 6, which provoked pouring emotions of grief

and anger. Chinese state media Global Times and People’s Daily, and the World

Health Organization posted on their Twitter accounts consecutively and

respectively confirming Dr. Li’s death around 11pm. But rumors went into

overdrive around the same time claiming Li was still in critical condition on extracorporeal

membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and under emergency treatment. On top of a wave of

prayers on social media for a miracle to bring Li back to life, news about his

death on any news media—including the tweets posted by Global Times and

People’s Daily—soon evaporated. Accompanying the growing anger, deep grief and

desperate hope, two hashtags #WuhanGovernmentOwnsDrLiAnApology and

#WeWantFreedomOfSpeech were trending on the Chinese Twitter-like social media

platform Weibo with a vast outpouring of support and acknowledgement of the

call for the basic human right.

These conflicting reports ended with a declaration of Li’s death from the hospital announced close to 4am on February 7, endorsed by the two state mouthpieces previously mentioned, again on Twitter. In the morning of the day, the short-lived activism on social media to fight against bureaucracy and for free speech was all gone, leaving behind only the state media’s narrative on heroism and resilience of the Chinese people as a collective in the crisis. The grotesque control on how an ordinary person dies is a nasty political ploy intended to pacify and dilute public fury but indeed stoked rages toward the legitimacy of the government. A professor of communication at Shenzhen University, Chang Jiang, sarcastically retweeted and commented on People’s Daily’s original announcement on Twitter about Li’s death, “People behind the [Great Fire] Wall do not fit to grieve, and have no right to pay their respects [to Dr. Li].”

Figure 1. Chang Jiang’s retweet of

People’s Daily’s post (author’s archive)

Compared

with the draconian cover-up of details about SARS in 2003, Chinese government

is ostensibly far more open in updating infected data. But the rare amount of

transparency sits in concert with the tightened grip on the information flow of

any narrative that goes against the grain. State media are rolling out messages

day and night: The epidemic is emergent but controllable; solidarity rises as

medics signed petitions to go to Wuhan for the virus war; international support

and applause is loud and clear; recovering stories of encouragement and

confidence are told. The vicissitudes of life with tears and rain of ordinary

individuals in infected areas can be diverted to the lowbrow sloganeering and media

coverage on the resign of local officials, disciplinary actions to party

members, critiques to the bureaucratism at the level of local authority, and,

of course, instructions from the top leaders that emphasize the safety of

ordinary lives.

China

has parallel worlds these days. The social media Weibo painfully reflects an

anarchical society, where desperate people in Wuhan crying out for help and

self-help, like any drowning man trying to catch at a straw. Volunteers are

quickly formed fragmented groups, swiftly organizing themselves to fill the

void of civil society, bypassing low-efficient bureaucracy to acquire, sort,

and deliver medical supplies, food, and other emergency items to hospitals, infected

complex, and people in need. However, because of the immaturity and rush, many

inexperienced volunteering groups have suffered. Stories spread out as some

volunteer groups got unqualified medical supplies that cost them money and time

and essentially do not help medics on the frontline of the virus war. Individual

agency and civil society that are denied by the totalitarianism are exactly the

things that can largely fill in the void created by complacency and conceit of

the system, and become accountable for ordinary lives. But the bottom-up narratives

about these lives and practices are rarely recognized as “official” news.

On

the contrary, official media keep their grand narrative, celebrating the

achievements in fighting against COVID-19, selecting-and-editing individual

stories that are full of warmth and encouragement, presenting hope and

solidarity, and constantly claiming and defending state’s authority over any other

information. Any incapability and ineffective handling of the situation only

happens and stays at the local/provincial level. Wuhan and Hubei governments’

slow reaction, disorganized organization, chaotic management, lack of

accountability led to underreporting of and even lies about the number of

infected cases and relevant information at the early stage of the epidemic. Yet

the big problem is that the close system of bureaucracy discourages officials

to take responsibility to anything that might not help or even hurt their

upward career, such as information on the outbreak of an epidemic, which is weighted

highly disastrous to one’s career than to lives of hundreds of millions.

Dr.

Li’s death further exacerbated the distance between these worlds. The officials

of stability maintenance and the vast censorship machine apparently did not

prepare for Li’s death. For a state that is taking its toll of structural

issues and the recent U.S.-China trade war, keeping up with its promises of

prosperity and success seems far hollower than ever before. Now the epidemic

brings a new crisis and issues that request new narratives to legitimize the

shaking foundation of governance. Dr. Li was a perfect fit for the new

narrative of what a positive resilient ordinary citizen can do in the national

crisis. Nevertheless, the censors haven’t got the scripts written down; Li

passed away, sarcastically leaving no time for a new script. Thus the

conflicting reports mirrored the indecision and confusion of the censoring machine.

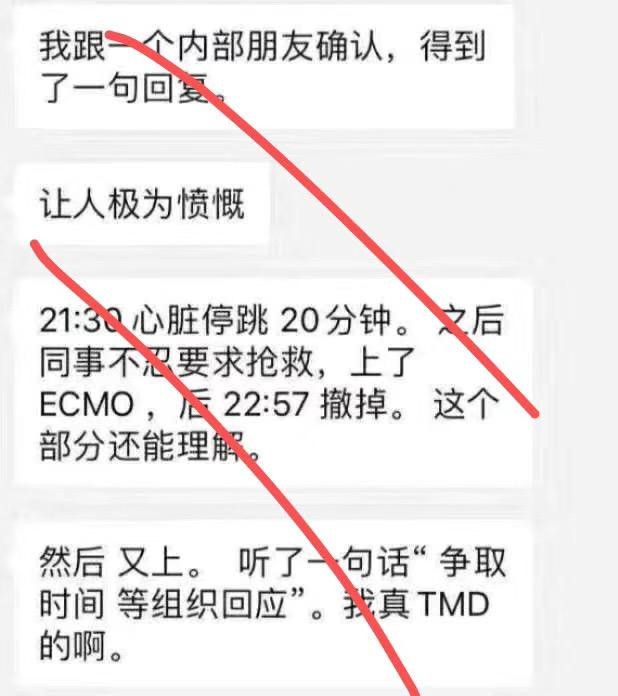

| I confirmed with a friend and got a reply

Which caused me indignation 21:30 [Li’s] heart stopped beating for 20 minutes. Colleagues really wanted to save him… so tried to put him on ECMO but eventually removed the machine at 22:57, which part I can understand. However, [ECMO] was soon put back again with someone saying that “…try to buy more time for officials to response [to how to handle the case]. Fuck them. |

Figure 2. Leaked WeChat conversations from people who worked in the hospital indicated an apparent maneuver over Li’s death (author’s archive, the red strike is a tactic to avoid being censored while sending the picture through the message app WeChat; translations by author)

But it soon got back on track. Online commentators claimed that a public opinion control tactic was deployed to delay emotion of people who raged over Li’s death. The dead-alive-dead narrative might be helpful to turn the public fury into the disappointment of hope, where angers were choked in the miracle that never comes. As rage spiked and people took to social media en masse for their short-lived protests over free speech, a leaked document of “Recommendations for Handling Netizen Reaction to Li Wenliang’s Death,” which analyzed public responses to Li’s death and provided policy suggestions to further censorship and propaganda, clearly demonstrated the ever-swift and sophisticated apparatus of ruling. Soon we heard on Central Chinese Television (CCTV) of highly recognition of Li the whistleblower’s heroic action and the call for enforcing accountability in local authorities of that the central government sent out a team to investigate issues related to Li as a response to “public opinion;” of more positive stories and achievements we have in the epidemic repeatedly. The grand narrative kept engineering to take over any individual story when it does not fit into the Great China/Dream discourse of a strong and powerful nation under the idolatry of the Big Brother.

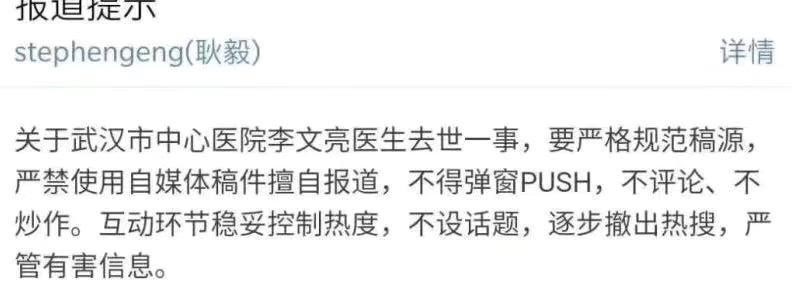

| Guideline for reporting On reporting Dr. Li’s death, [any reports] should be strict on controlling source information. It is forbidden to use any materials from self-media and conduct autonomous reporting. It is not allowed to have pop-up windows about the news appearing on any websites, or push the news through any apps, or have a comment section under the news in a website or an app to avoid hype. If interactive section is needed, control on the sensation is necessary. No topic discussion is allowed [on social media, supposedly Weibo], and the current trending topic of the news should be gradually taken down.[1] Any pernicious information should be under tight control. |

Figure 3. A leaked message on how

to report the death of Dr. Li (author’s archive; translations are mine.)

There is nothing new under the sun. China Digital Times put up a review of China’s handling of the epidemic which is comparable to the former Soviet Union’s action in the Chernobyl disaster,

“…this closed, arrogant, pre-modern power structure spends all of its time removing dissent and has completely lost the ability to correct itself. When faced with a public crisis, these officials are always putting stability maintenance before people’s rights. These outdated governing philosophies and capabilities, concealed by the old system, are now exposed. On this path of stubbornness and complacency, where bad habits die hard, how similar is this to Chernobyl’s Bridge of Death?”

Figure 4. An artist illustrating

young people’s illusion of the free will under propaganda in China (courtesy of

Matsuyama Miyabi, more of her work at www.matsuyamamiyabi.com)

[1] On Weibo, hashtag is associated to a specific section called Huati, literally meaning the topic. Users can create different topic pages in this section, and the name of the page, i.e., topic, is a hashtag. By tagging the topic, different posts by different users will flow under the same page, much similar to Twitter’s hashtag page. When a topic page is deleted in Huati section by Weibo, users can still post with the hashtag but no longer able to construct conversations in a separate page.