The medieval writer made puzzling references to a story called “The Song of Wade,” which has been lost to history. Only a few lines quoted—or perhaps misquoted—in a 12th-century sermon survive

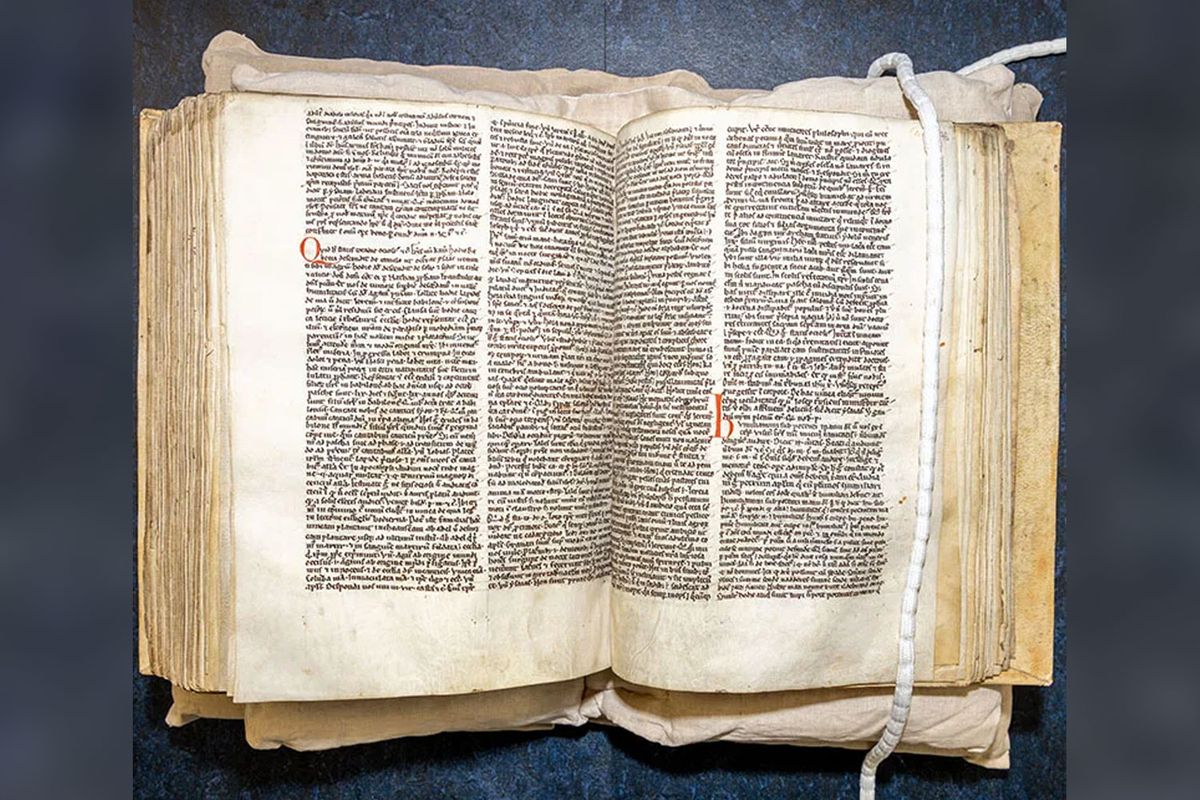

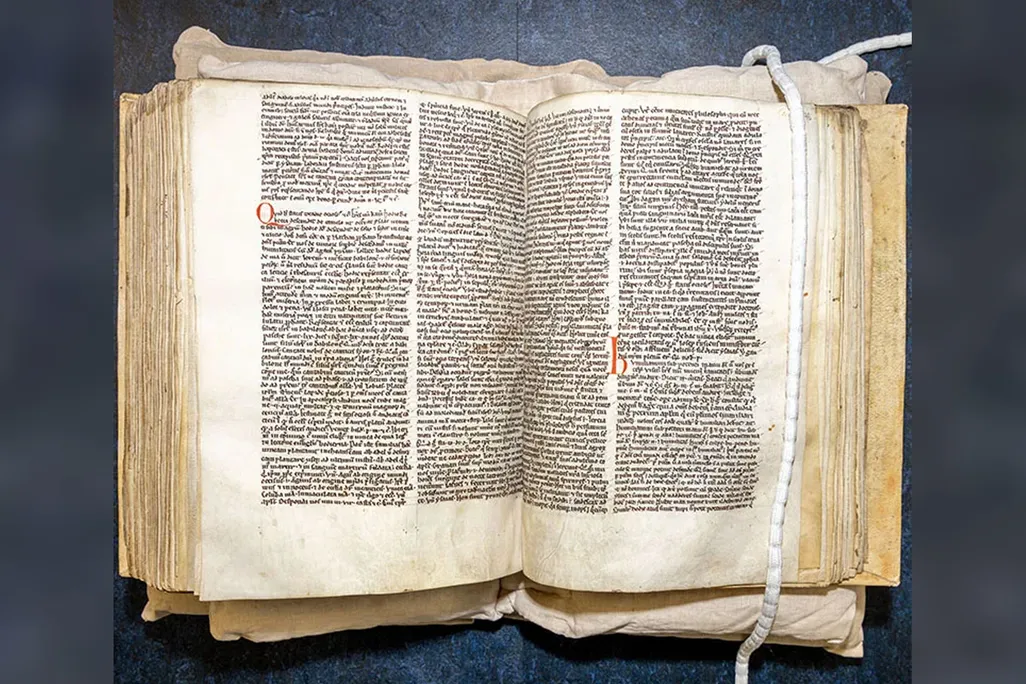

The manuscript that contains excerpts from The Song of Wade

The Master and Fellows of Peterhouse, University of Cambridge

Throughout history, connecting with younger generations has always been a challenging pursuit.

But in the 12th century, one brave preacher gave it his best shot, delivering a sermon in Latin that included a brief pop culture reference. While we don’t know whether he successfully kept his medieval congregation entertained, the sermon has captured the interest of literary historians through the present day.

Rediscovered in 1896 in the University of Cambridge’s archives, the sermon quotes several lines from The Song of Wade, which was a popular romantic poem at the time.

“Here we have a late-12th-century sermon deploying a meme from the hit romantic story of the day,” Seb Falk, a historian at the University of Cambridge, says in a statement. “This is very early evidence of a preacher weaving pop culture into a sermon to keep his audience hooked.”

The Song of Wade was so well-known in its heyday that major European writers continued to cite the story in their works for several centuries. Readers seemed to know enough about Wade to immediately understand any references to him, so writers typically mentioned the character with little other context. If you knew, you knew.

Seb Falk and James Wade, the authors of the new study The Master and Fellows of Peterhouse, University of Cambridge/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ff/50/ff501ec7-4a62-410a-83f1-7718d229992a/15int-uk-chaucer-vjcz-superjumbo.webp)

But today’s readers lack that familiarity. No physical copies of The Song of Wade have survived, forcing historians to speculate about what exactly the poem may have said. The few lines quoted in the preacher’s sermon are the best direct links to understanding both the poem and subsequent texts alluding to it—which include, most notably, two pieces by Geoffrey Chaucer, including one story from The Canterbury Tales.

But the exact wording of the sermon itself—copied by a scribe in an unsteady calligraphy—has been the subject of debate since at least the late 1500s.

“Lots of very smart people have torn their hair out over the spelling, punctuation, literal translation, meaning and context of a few lines of text,” James Wade, a literary scholar at the University of Cambridge who has no relation to the poem’s titular character, says in the statement.

Now, Falk and Wade think they have made a breakthrough. In a study published this week in the journal The Review of English Studies, the researchers argue that the modern English translation of the poem from the sermon contains a typo.

For more than a century, scholars had assumed that an excerpt from the poem read: “Some are elves and some are adders; some are sprites that dwell by waters.” The passage suggests the poem deals in a world of magical or mythological creatures.

Quick fact: What is The Canterbury Tales about?

Written in the 14th century, Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales include 24 stories told by pilgrims traveling to the shrine of St. Thomas Becket in Canterbury, England.

In the new study, Falk and Wade suggest the scribe incorrectly transcribed two key words that place The Song of Wade within an entirely new context.

Their new translation reads: “Some are wolves and some are adders; some are sea-snakes that dwell by the water.”

Changing “elves” and “sprites” to “wolves” and “sea-snakes” “shifts this legend away from monsters and giants into the human battles of chivalric rivals,” says Falk in the statement. The images are more grounded in the tribulations of romance, which the researchers argue also better fit Chaucer’s later allusions to the poem.

“There is nothing mythological in it,” Wade says in a video released by the university. “It’s a story of human aggression, a story of chivalry, a story of courtly intrigue and a story of fin’amor. And that makes much better sense with the way that Chaucer is using this reference in his writings.”

In his poem Troilus and Criseyde, the character Pandarus tells the story of Wade to a woman to “stir her passions,” per the statement. And in The Canterbury Tales’ “The Merchant’s Tale,” Wade is evoked during a discussion of marrying younger women.

Some experts say the new study could help deepen our understanding of medieval literature.

“I think they are right that he must be a knight from a lost romance rather than a giant from English folklore,” Richard North, a literary scholar at University College London who was not involved in the study, tells the New York Times’ Stephen Castle.

However, others have urged caution. “I’d be cautious about claiming this is a revolutionary way of understanding Chaucer,” says Stephanie Trigg, a literary scholar at the University of Melbourne, to the publication. “They really thicken the net of allusions and references that sit behind these tantalizing fragments. Am I convinced that our reading of either Chaucerian text is going to change dramatically? Not really.”

This isn’t the first time that Wade’s scholarship has generated headlines. Two years ago, he found a medieval comedy routine inside a 15th-century text called the Heege manuscript. The text revealed that medieval minstrels had “the instinct to self-ironize, to use crude bodily humor, to use slapstick and situational comedy, and the willingness to make the audience the butt of the joke,” Wade told Salon’s Matthew Rozsa in 2023.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ChristianThorsberg_Headshot.png)