Telescopes detected the first stages of hot minerals condensing from gas around a young star called HOPS-315

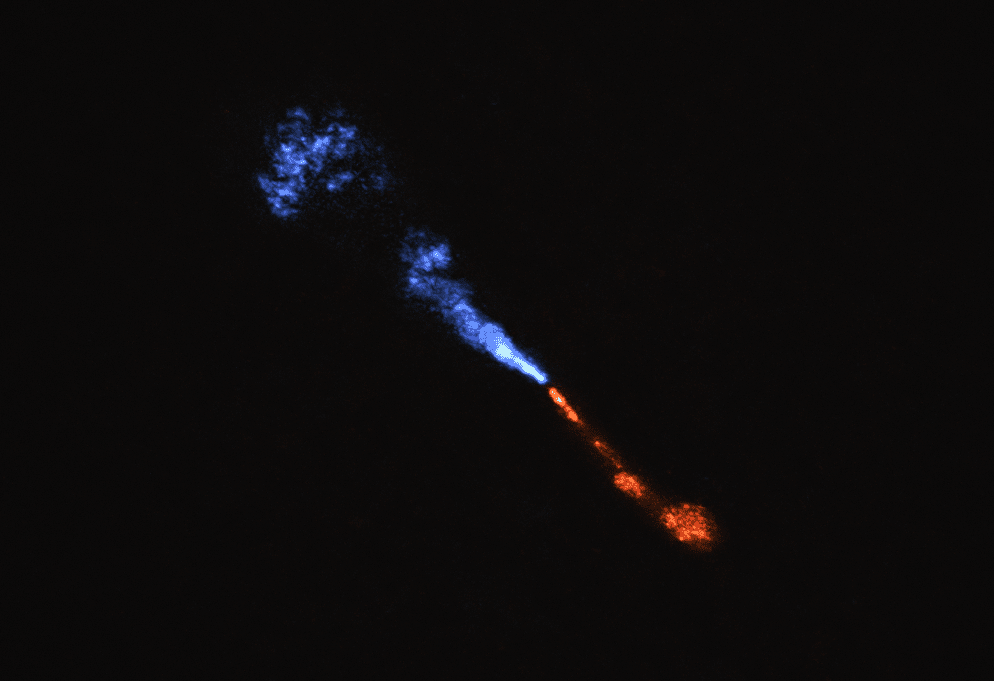

An image from the ALMA telescope array in Chile shows jets of silicon monoxide blowing away from the young star HOPS-315. The blue jet is moving towards Earth, and the red jet is moving away from us.

ESO

When scientists want to understand the earliest history of our Solar System, they’ve typically turned to ancient meteorites. These celestial objects that come to Earth are remnants of the building blocks of the planets, and scientists have learned a lot from studying them. However, astronomers have long been on the lookout for a way to watch the early formation of planets as it happens.

“What we’ve been trying to do is find a baby version of our Solar System somewhere else,” Merel van ’t Hoff, an astronomer at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, tells Nature’s Jenna Ahart.

In images captured by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope and the European Southern Observatory’s ALMA telescope in Chile’s Atacama desert, researchers have done just that, according to a study published in the journal Nature. These telescopes caught the action around HOPS-315, a ‘baby’ star that’s only 100,000 to 200,000 years old and about 1,300 light-years away from Earth. The images and data captured the hot region around the protostar where Earth-like planets form, and show gaseous silicon monoxide condensing into solid silicate minerals—the same materials that make up the vast majority of Earth’s crust.

Since the researchers observed silicon in both a gaseous and crystalline state, they concluded that they’ve captured the very earliest stages of planet formation. “For the first time, we can conclusively say that the first steps of planet formation are happening right now,” Melissa McClure, an astronomer at Leiden University in the Netherlands and lead author of the new study, tells the AP’s Marcia Dunn.

Previously, this phenomenon hadn’t been witnessed directly, and meteorites were the only source for information about the early formation of our Solar System. However, advances in newer telescopes like ALMA and the James Webb Space Telescope offer researchers opportunities to observe the process in real time and then make conclusions about planetary history closer to home.

“We’re really seeing these minerals at the same location in this extrasolar system as where we see them in asteroids in the Solar System,” says co-author Logan Francis, an astronomer at Leiden University, in a statement, referring to the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter in our solar system.

Even though HOPS-315 is 1,300 light-years away—and a single light-year is about six trillion miles—these new observations are exciting for scientists interested in our own cosmic neighborhood.

Van ’t Hoff tells the AP that researchers are excited that this discovery could lead to finding more newly forming systems, and even lead to a better understanding of our own place in the universe. “Are there Earth-like planets out there or are we like so special that we might not expect it to occur very often?”

Scientists hope this is just the beginning of new discoveries about how solar systems gel together in their earliest stages.

“I think this is the first time we’ve gotten a view of this process,” John Tobin, an astronomer at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory who was not involved in the new study, tells Nature. “But we’re really just scratching the surface.”