Sixty-five years after it first hit store shelves, the iconic, red-framed drawing toy continues to enchant kids, artists, and collectors alike

:focal(1000x752:1001x753)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f3/55/f355a78f-b7d2-4c32-958f-89cb5a362ddb/nmah-etch_a_sketch.jpg)

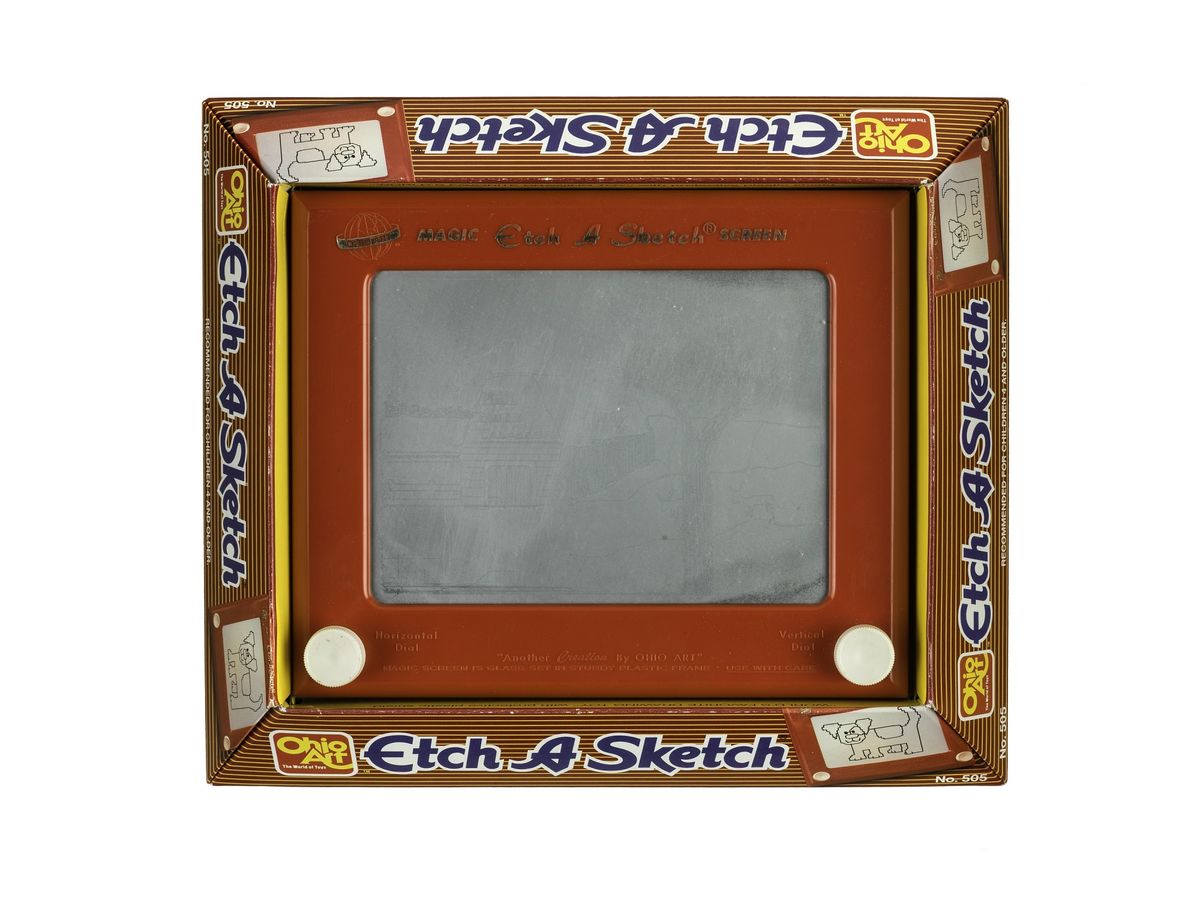

The Smithsonian’s own Etch A Sketch, acquired in 2011, is displayed as a cultural artifact—a symbol of a toy that has shaped generations.

National Museum of American History

Kevin E. Davis doesn’t fixate on the Etch A Sketch’s left and right knobs when he sits down to draw. “I’m thinking about the line I want to draw, and my hands just make it happen,” says the 54-year-old artist. His fingers trace paths with muscle memory that’s been honed over hundreds of drawings—everything from a cartoon portrait of Toy Story’s Woody to an architectural sketch of Germany’s Neuschwanstein Castle.

The Las Vegas-based California native, who works for an auto insurance company in its claims department, creates Etch A Sketch art as a hobby. At the end of his workday, before dinner’s ready, Davis goes live on TikTok and YouTube, taking requests for subject matter. He spends about 15 to 30 minutes on each drawing.

For many, the Etch A Sketch is a classic toy from their childhood. To Davis, it’s a canvas. He draws replicas of masterpieces like Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, the two cherubs from Raphael’s Sistine Madonna and Donatello’s David, as well as depictions of fictional characters such as Beetlejuice and the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

As the Etch A Sketch celebrates its 65th anniversary this summer, cultural historians, curators, toy experts, users and its manufacturers agree that the power of the multigenerational toy lies in its simplicity, durability and emotional resonance.

“A lot of people, when I’m live, will say, ‘I haven’t seen that in years. I haven’t played with that since I was a kid,’” Davis says. “It’s that nostalgia that brings it back to life and keeps it going. No question about it.”

Did you know? Etch A Sketch at the Smithsonian

- The Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History acquired an Etch A Sketch in 2011.

- The drawing toy is on display in the exhibition “Inventing in America,” a collaboration with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

A magical screen from France

The Etch A Sketch’s story begins in 1950s France, where electrician André Cassagnes invented a drawing toy using static electricity and aluminum powder. The initial discovery of the toy’s mechanics was accidental.

“While fitting a light-switch plate in a factory, Cassagnes noticed that after he had peeled a sheet of protective plastic from the plate, pencil marks made on one side transferred to the other side,” wrote the Guardian’s Kim Willsher in an obituary when the inventor died in 2013. “The factory made a wall covering and used metallic powders. Powder particles had clung to the underside of the plastic sheet, and with the help of static electricity stayed there. Cassagnes’ pencil marks had displaced them, tracing visible lines through the powder.”

But it wasn’t until an American toy company took a leap of faith that Cassagnes’ L’Écran Magique—the Magic Screen—found its iconic identity.

Ohio Art Company initially passed on the toy when its employees saw it at the 1959 International Toy Fair in Nuremberg. But after a fortuitous second look at a trade show in New York, the outfit invested a risky $25,000—more than it had ever paid for a toy license at the time and the equivalent of about $272,000 today—and rushed to manufacture in time for the 1960 holiday season. Ohio Art renamed the toy “Etch A Sketch” and spent heavily on a television ad campaign—a relatively novel strategy at the time. Priced affordably at $2.99, the company sold 600,000 units that year alone.

“They were kind of intimidated by putting all that money down on this one untried concept,” says Christopher Bensch, vice president for collections at the Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, New York. “But it certainly paid off for them.”

Bensch sees the Etch A Sketch as more than just a consumer hit. “It’s the Etch A Sketch,” he says. “There’s no other category of drawing screens with two knobs and a pressed plastic frame—there is no generic form of it.”

A toy that drew its own path

Inside the signature red frame is a simple yet clever mechanism: a stylus, suspended between layers of aluminum powder and glass, that scrapes the top aluminum layer to reveal dark lines. The left knob moves the stylus horizontally; the right knob, vertically. Mastering both at once takes skill. As if magically, to erase, the user just shakes the drawing board.

Kevin E. Davis creates Etch A Sketch art as a hobby. Courtesy of Kevin E. Davis/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/05/ed/05ed56ba-4cd9-40a3-a80a-ae203c24b424/kevin_selfie.jpg)

For artists like Davis, understanding those mechanics is part of the art itself. “You’re not really drawing a line,” he explains. “You’re creating a negative space. … It’s black because the backing is black.” Through 30 years of experimentation, he’s even advanced techniques like two-tone shading and disconnected lines by shaking or pushing powder in specific ways, mimicking light and shadow.

Davis is not alone. He is part of a Facebook global community of about 170 Etch A Sketch artists that has emerged with the rise of social media. They share their work and methods as they learn and perfect them. “We’re more of a family. We’re not in competition with each other,” Davis says. “We are people using the same canvas, but the art is unique.”

In an age of apps and tablets, it is impressive that a mechanical toy introduced in 1960 continues to thrive. But there is some logic behind its staying power: “It’s beautifully self-contained. It doesn’t need any batteries,” Bensch says. “It is a way lower price point than even the most basic tablet, and when it drops on the ground and cracks, it is not quite as much of a crisis as it is for that expensive tablet.”

Debbie Schaefer-Jacobs, curator and expert in educational toys at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, points out that the Etch A Sketch is not only simple but also sustainable. It’s a drawing tool, but “it’s environmentally friendly because you’re not wasting paper.” As children graduate from an Etch A Sketch to crayons and then to paint or digital tablets, the toy often serves as a first step in a creative journey, she adds.

And it’s durable. “It can last 20 or 30 years even with hard use,” she says. “Much better than a tablet for sure.”

That longevity is part of why the Etch A Sketch was inducted into the Strong Museum’s National Toy Hall of Fame in 1998. “There are some things like Silly Putty and Play-Doh and Etch A Sketch and Radio Flyer Wagon that are classics,” Bensch says. “They are not the ones that you got from your grandparents, and you had to fake a smile and shove them under your bed after that birthday party and never play with them again.”

Ohio Art tried introducing electronic versions of the Etch A Sketch, as well as various branded or specialized versions—for instance, in the shape of hearts for Valentine’s Day, Christmas trees and Homer Simpson. Still, Bensch says, “The one that sticks in people’s minds and the one that continues to sell is the simple red-framed Etch A Sketch that looks pretty much identical to the one that came out in 1960.”

Pop-culture fame and lasting craftsmanship

One of Etch A Sketch’s biggest career moments came in 1995—35 years after its debut—when it made a cameo in Pixar’s Toy Story. The animated red frame had a playful quick-draw gun duel with Woody, bringing the toy to life for a new generation.

“It got a new breath of life thanks to those movies,” Bensch says. After its appearance in the first Toy Story film, sales jumped by 20 percent. The cameo didn’t just revive interest—it repositioned Etch A Sketch from a nostalgic relic to a pop-culture icon.

The toy’s signature silhouette has appeared in Elf, “The Simpsons,” political metaphors (“You hit a reset button for the fall campaign, everything changes. It’s almost like an Etch A Sketch.”) and even music videos. “Cartoons over the years have mentioned Etch A Sketch … hundreds, maybe more,” says Bill Killgallon, former president of Ohio Art and son of William Casley Killgallon, who was Ohio Art’s vice president when it acquired the rights to the toy.

That recognizability has made the toy a favorite among advertisers. “Its silhouette is so distinct that it’s instantly understood,” says Elena West, current CEO of Ohio Art and Bill Killgallon’s niece.

Beneath the fame was a toy built to endure. The original Etch A Sketch was manufactured with meticulous care in Bryan, Ohio, where workers—some employed on the line for more than four decades—took immense pride in its production. “They wouldn’t let just anyone work on that line,” says West. “The process was incredibly precise.”

That precision was necessary. “It still is a very, very difficult toy to make because of the internal components,” says Killgallon. “It has to be assembled in a cool, dry environment. The glass had to be ultra-clean—no fingerprints or oils, or the aluminum powder wouldn’t stick properly.” Even the water used to clean the glass had to be purified and heated to high temperatures to avoid residue, he adds.

Originally assembled with glass screens and metal parts, Etch A Sketch eventually transitioned to plastic to meet safety standards. But its core design—gray screen, red frame, white knobs—largely remained the same. “There was a culture of ‘Don’t change it,’” Killgallon says. “Eventually, we got through that culture, and we made many different kinds of Etch A Sketches—smaller Etch A Sketches called ‘pocket,’ intermediate-size Etch A Sketches called ‘travel’ and, of course, then we licensed other products like Disney Etch A Sketches and many other popular children’s programs.”

In 2001, rising production costs and stagnant retail prices forced Ohio Art to relocate Etch A Sketch manufacturing to China. The decision was partly driven by pressure from major retailers to keep prices low, leaving the company with little room to maintain profitability. “It came to the point where we just couldn’t afford this anymore—the profitability of the product going down,” Killgallon says. “It was influencing our other business decisions in the company, so we moved the production to China.”

Though Ohio Art eventually sold its toy business in 2016 to focus on its lithography business, the Etch A Sketch is still part of its roots. “We were fortunate to be the originals—the O.G. of this mechanical drawing toy,” West says.

Even after the sale to Canadian toy company Spin Master, West still hears from fans. She once received a letter from a child who mailed in $2 hoping to join the long-defunct Etch A Sketch Club. “I had to go through all of our archives, but I found the coveted Etch A Sketch Club patch that we used to send these kids once they joined,” she says. She still gets calls asking for replacement knobs on vintage units.

The art lives on

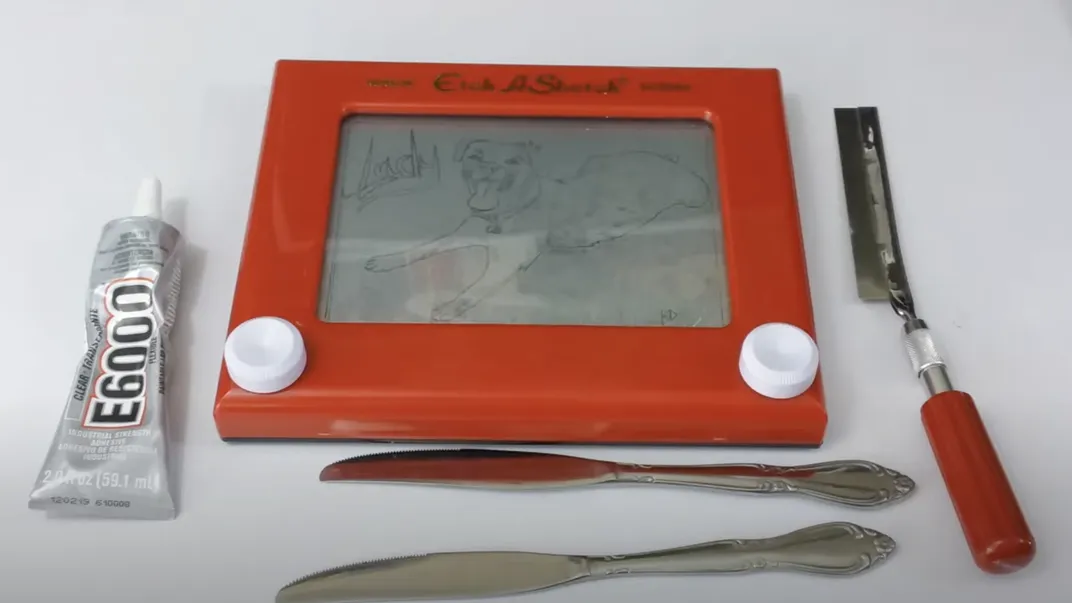

Davis, who now preserves his work by opening up the toys, cleaning out unused aluminum powder and sealing them shut, sees his art as part of a broader mission. “I 100 percent feel that it’s Etch A Sketch artists like myself, who are out there in social media posting their drawings, who are also helping keep it alive.”

Germany’s Neuschwanstein Castle Courtesy of Kevin E. Davis/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/60/3a/603af403-130e-4eb1-b26f-4272a1eb0aec/castle_kevind.jpg)

Five years ago, for the 60th anniversary, Davis redrew Neuschwanstein Castle, 25 years after his original. Courtesy of Kevin E. Davis/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/55/51/5551469d-1de2-441f-b48b-42aa69340c66/castle_remake_kevind.jpg)

From drawing contests with his 10-year-old daughter to celebrity collaborations, Davis has etched more than 300 pieces—and still uses some of the same boards he started with decades ago. Five years ago, for the 60th anniversary, he redrew Neuschwanstein Castle, nearly 25 years after his original. The work is a reflection of his growth and patience.

Davis, along with other artists and collectors, receive anniversary care packages from Spin Master to commemorate special anniversaries or editions. “I have no question the Etch A Sketch will be here at the 100th anniversary,” he says.

Headquartered in Toronto, with offices worldwide, Spin Master distributes toys—including its famous Kinetic Sand and “Paw Patrol” products—in 100 countries. It is one of the largest toy manufacturers globally, says Tammy Smitham, spokesperson for the company.

In 2020, Spin Master, which continues to manufacture the Etch A Sketch in China, launched a series of limited editions to celebrate the toy’s 60th anniversary. It included Etch A Sketches inspired by NASA, Monopoly, the Rubik’s Cube and comics creator Stan Lee. At that moment in history, 175 million Etch A Sketches had been sold around the world. Today, prices typically range from around $8 for the pocket-size version to about $30 for standard-sized special editions.

Etch A Sketch is for everybody, Smitham argues. “From someone who’s just starting out, all the way to these amazing artists,” she says. “It’s still something that endures the test of time. … And we’ll do our best to continue to steward it into the future.”

The Smithsonian’s own Etch A Sketch, acquired in 2011, is displayed as a cultural artifact—a symbol of a toy that has shaped generations. “It’s not an overly expensive toy,” Schaefer-Jacobs says. “The kind of toy you can share in a family.”

Bensch agrees. The Etch A Sketch is “an evergreen toy that so many toy manufacturers yearn for,” he says. “One of those toys that parents and grandparents pass down to new generations.”

Sixty-five years after its launch, the Etch A Sketch remains what few toys ever become: timeless.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/aurora.png)