A Smithsonian magazine special report

Vague phrasing in the state’s Revolutionary-era Constitution enfranchised women who met specific property requirements. A 1790 law explicitly allowed female suffrage, but this privilege was revoked in 1807

An 1880 Harper’s Weekly illustration titled Women at the Polls in New Jersey in the Good Old Times

Historica Graphica Collection / Heritage Images / Getty Images

Key takeaways: The first women voters in American history

- New Jersey’s 1776 State Constitution allowed “all inhabitants,” with some exceptions, to vote in state elections. Women took full advantage of this vague wording, with no fewer than 163 casting their ballots between 1797 and 1807.

- In 1807, male legislators restricted the vote to “free, white, male citizens.”

The first New Jersey State Constitution, like many others written during the early months of the Revolutionary War, was drafted in a hurry. State legislators were so eager to create a governing blueprint that they drafted and then ratified the document in a matter of days. New Jersey formally adopted its State Constitution on July 2, 1776, two days before America declared its independence from Great Britain on July 4.

While some state constitutions defined voters as a “man,” “male white inhabitants,” a “freeman” or a “free white man,” New Jersey extended suffrage to “all inhabitants” of the state who were over 21, had resided “within the county in which they claim a vote” for the previous year, and were “worth £50.” According to historians Neale McGoldrick and Margaret Crocco, an estimated 95 percent of the state’s white male population met that final qualification. While the law excluded married women whose property had transferred to their husbands upon marriage, landowning women (either widows or unmarried individuals), who made up around 5 percent of the population, gained full enfranchisement, as did free African Americans.

Much of the anecdotal literature classifies the New Jersey Constitution’s voting qualifications as either accidental or inconsequential. In a 1990 essay, historian Irwin N. Gertzog argued that the document’s use of the phrase “all inhabitants” was a way of rewarding New Jersey’s men for their support of the patriot cause. “Until then,” Gertzog wrote, these men “had been unable to satisfy more proscriptive eligibility requirements.” Now, however, “the framers of the [New Jersey] Constitution were sending a signal to the men who would finance and fight the war that the new state was prepared to be generous in the distribution of political rights.”

The 1776 New Jersey State Constitution enfranchised “all inhabitants of this colony of full age, who are worth £50 … and have resided within the county in which they claim a vote for 12 months immediately preceding the election.”/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d7/b7/d7b7fd87-8ab9-434d-98cf-e463b13dfe9e/const76-3.jpg)

Because women had not voted prior to the American Revolution, Gertzog reasoned that the framers assumed the status quo would continue during and after the war. As such, they did not feel the need to specifically exclude women and African Americans from the voting qualifications. “All inhabitants,” in this case, was understood to mean free white men.

Jan Ellen Lewis’ 2011 paper challenged Gertzog’s interpretation. Then a historian at Rutgers University, Lewis suggested that the State Constitution’s language was “rather carefully crafted, the product of compromise” instead of an oversight. Her research indicated that the New Jersey Provincial Congress’ early drafts of the document underwent multiple language changes in late 1775 and early 1776. At least one version used the specific word “he” when identifying voters, but later drafts replaced the pronoun with more gender-neutral language, pointing to a deliberate change.

While various states included similarly vague phrasing in their constitutions (just five explicitly limited the vote to men in their first versions), New Jersey was the only place where women actually took advantage of the loophole to turn out at the polls in the early years of the nation’s history.

If the initial impetus for allowing women and free African Americans to vote in New Jersey was unclear, a subsequent election law change made the state the first in the Union to officially enfranchise women. The State Constitution’s wording was open to interpretation, but the 1790 Electoral Reform Enrolled Law specifically noted that voters in seven New Jersey counties could cast a ballot wherever “he or she” resided.

The name “Mary Norris” appears on this 1801 poll list from New Jersey’s Montgomery Township. Museum of the American Revolution/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8e/47/8e470907-daa7-495e-bdd4-9c96c2c0be59/name.jpg)

According to the Museum of the American Revolution, which explored the stories of the United States’ first female voters in a 2020 exhibition, the counties in question were closely affiliated with both the Quakers and the Federalist Party. “This has led many historians to suggest that perhaps the 1790 statute was influenced by those groups—the Quakers because of their egalitarian views, and the Federalists because they hoped to widen their political base and increase their legislative power,” the museum notes on its website.

Scholars are unsure exactly why New Jersey emerged as an early promoter of women’s voting rights. Carol Berkin, an emeritus historian at CUNY Graduate Center and the author of Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America’s Independence, suggests that the answer lies in long-overlooked historical documents. “Most people who talk about this topic devote only an hour or a paragraph and a half to it,” she tells Smithsonian magazine. “It’s possible to find out, if anybody wants to take up the project, to try to find the letters and papers of all the men in the legislature at the time, to see if any of them mention why they did this.”

Historians have largely discredited the idea that Joseph Cooper, a Quaker legislator mistakenly identified as a committee member who helped draft the 1790 law, was the one who championed using the word “she” in the statute. Berkin, for her part, calls the “Quaker narrative” feasible but ultimately conjecture. “New Jersey had a large Quaker population,” she says, “and in order to get people to support the Revolution, which the Quakers did not want to do, [state lawmakers] could have held out the possibility that women and African Americans might benefit from joining the war effort.” She describes this approach as “holding out a carrot” as opposed to a stick.

Berkin believes that framing New Jersey’s enfranchisement as a push to win female support for the Revolution is too broad. “What really prompted the people to support the Revolution most often was the arrival of the British Army,” she says, “because [some soldiers] behaved so badly,” plundering colonists’ farms and raping women and girls. After such acts of violence, Berkin adds, many “men decided they wanted to support the Revolution.”

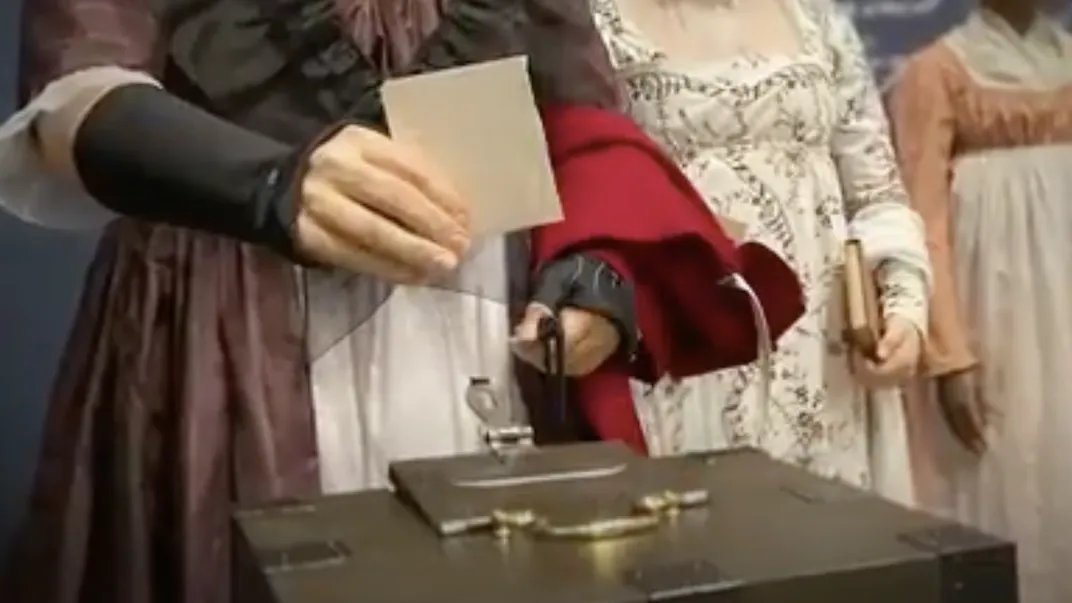

A tableau of female voters during the Revolutionary era, as featured in the “When Women Lost the Vote” exhibition Museum of the American Revolution/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/83/1a/831aace6-37cd-4b70-bf8f-e23c469b81d0/img_e7144.jpg)

In 1797, a new state law expanded voting rights to women throughout New Jersey, in addition to dropping the phrase “clear estate” (meaning clear property ownership) from the voting requirements. This change, according to the Museum of the American Revolution, might “have been a subtle but dramatic win for women voters,” allowing them to cast their ballot “even if their legal ownership” of land was unclear, as was sometimes the case with widows and wives.

Experts don’t know exactly how many women in New Jersey exercised their right to vote. Overall voter participation in the state rose from 8,580 in a 1791 congressional election to 18,967 in 1798. Federalist pamphleteer William Griffith, who advocated for women’s disenfranchisement, estimated in 1791 that the number of eligible female voters neared 10,000, but he was far from an unbiased source. A more recent survey by the Museum of the American Revolution analyzed 18 poll lists spanning 1797 to 1807, half of which included women’s names. In total, these female voters represented an estimated 7.7 percent of the ballots cast.

Following the 1797 statute’s passage, members of both nascent political parties, the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans, initially seemed ambivalent about women’s suffrage. As scholars Judith Apter Klinghoffer and Lois Elkis wrote in a 1992 journal article, “It took politicians some time to assess which party stood to benefit most from the female vote.”

John Condit/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3b/09/3b09bd8d-67bc-4513-85ca-b9ec01773477/john-condit.jpg)

The issue of women’s suffrage came to a head in Elizabethtown’s 1797 congressional election. Hoping to secure candidate William Crane’s victory over Democratic-Republican John Condit, local Federalists reportedly rushed in 75 women in a last-ditch effort to swing the race in their favor. Despite these additional Federalist voters, Condit won by 93 votes.

The Newark-based Sentinel of Freedom published a poem satirizing the Federalists’ failed plan, writing, “While men of rank, who played this prank, / beat up the widow’s quarters; / Their hands they laid on every maid, / and scarce spared wives or daughters!” Soon, the election sparked a general sentiment that women did not belong at the polls, that they were no more than pawns swayed by the men around them, incapable of independent thought. Both parties echoed this argument over the next decade. Berkin says that the 1797 Elizabethtown election “sent up a warning that women voters could be dangerous, that they could shape elections.”

Griffith played a large role in fueling the blowback. “It is perfectly disgusting to witness the manner in which women are polled at our elections,” he wrote in a 1799 pamphlet. “Nothing can be a greater mockery of this invaluable and sacred right than to suffer it to be exercised by persons who do not even pretend to any judgment on the subject.”

Democratic-Republicans also chimed in on women’s suffrage after the too-close-for-comfort 1802 Hunterdon County election, in which accusations of voter fraud by married women, enslaved individuals and out-of-state residents ran rampant. Two years later, in 1804, Democratic-Republicans accused Federalists in Amwell of “dragg[ing] their women voters out by wagon loads through the rain and cold,” according to a contemporary source. By then, wrote Campbell Curry-Ledbetter in a 2020 journal article, the implication was clear: “Women voting, though legal, constituted political corruption and was antithetical to democracy.”

This sentiment came full circle in 1807, during an internal Democratic-Republican battle to move the Essex County Courthouse from Newark to Elizabethtown. While the former won the fight, New Jersey’s female enfranchisement—the first of its kind in the United States—was lost as a result of the widespread corruption that plagued the referendum. Newark won the contest by a margin of 7,666 to 6,181; an impossible 279 percent of Essex County’s legally eligible voters had turned out for the referendum. Both sides accused the other of voter fraud, prompting state legislators to declare the election “illegally conducted” and overturn its result. These men proposed sweeping changes to the law, and women, as had already been the case in the popular press, emerged as the scapegoat.

Introduced in 1807, New Jersey’s next major election law declared, “From and after the passing of this act, no person shall vote in any state or county election for officers in the government of the United States or of this state, unless such person be a free, white, male citizen of this state.” With that one sentence, the measure revoked suffrage for women and free African Americans in New Jersey. The law went into effect without much of a debate, earning overwhelming bipartisan support. “In the end, the story is really about what happens when political parties battle each other,” says Berkin. “The one thing they agree on is the narrative [of close, corrupt elections being] easier to manage if we get rid of these unpredictable voters, women and Black men.”

As Gertzog put it in his 1990 essay:

[Women] lost the vote not so much because a few … had engaged in illegal behavior in an Essex County referendum; they were deprived of the vote largely because, as women, unable to hold public office and forbidden by the norms of the period from resorting to tactics fostering political mobilization, they could not protect themselves from a resourceful majority who wanted to reform the election process and believed that it was in their own interests to disenfranchise politically marginal groups.

According to Klinghoffer and Elkis, “Women lost not only their right to participate in the political process but also their image as virtuous individuals.” Now seen as irrational and easily influenced, they were deemed “incompatible with the independence of heart and mind so essential to those deemed fit to be active participants in the body politic.” An 1808 Trenton Federalist article blamed women and Black Americans for making the state’s elections “disagreeable, contentious and corrupt.”

A page from the 1807 electoral reform law, which disenfranchised women and Black Americans New Jersey State Archives/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7b/37/7b370cd8-8573-4735-b4d0-80a312f3fbb9/1807.jpg)

Seventy-three years after New Jersey’s women lost the right to vote, suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton attempted to cast her ballot in the 1880 presidential election in her hometown of Tenafly, located north of Newark near the state border with New York. Joined by Susan B. Anthony, who had previously been arrested for voting illegally in the 1872 presidential election, Stanton “had great fun frightening and muddling those old Dutch [voting] inspectors,” as she later recalled. A direct challenge to discriminatory laws against women, Stanton’s symbolic act left “the whole town … agape,” she remarked with relish.

New Jersey only welcomed women back to the polls as of February 9, 1920, when the state ratified the 19th Amendment. Nationwide ratification followed a few months later, on August 18. Though the first women to cast their ballots in Colonial America didn’t live to see their peers regain the right to vote, suffragist leaders like Stanton and Anthony kept these trailblazers’ memory alive into the 20th century.

New Jersey’s brief period of female enfranchisement “does not die [in 1807],” says Berkin, “but becomes part of the genuinely feminist campaign, not just for suffrage, but for women’s rights,” The historian adds, “It is kept alive decades later after it ends because these feminists, led by Stanton and others, understood that it was good to be able to point to a moment in the past when women had that right.”

Suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton (seated) and Susan B. Anthony (standing)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6c/fa/6cfad22a-8e9b-4207-a0ea-e84f2adb96e7/service-pnp-cph-3a00000-3a02000-3a02500-3a02558v.jpg)