:focal(363x276:364x277)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6d/3a/6d3a241f-efe1-4a10-a28c-8d290c3377c2/edmond_dede.jpeg)

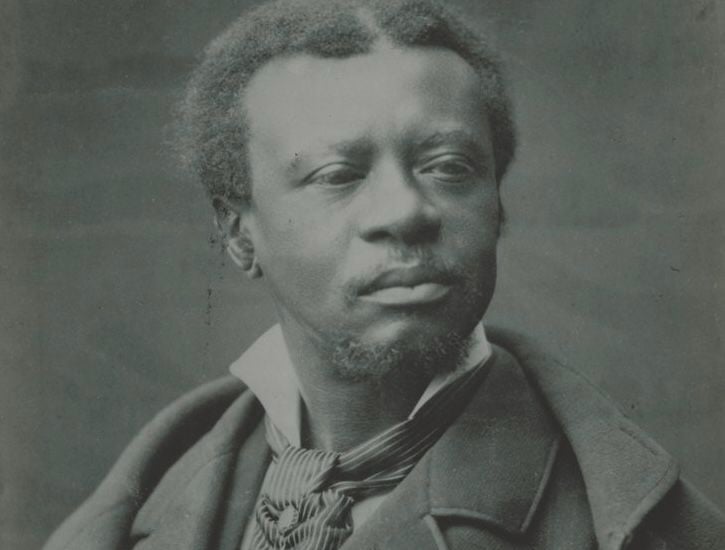

Edmond Dédé, a talented composer who is finally getting his due

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

In the early 1800s, New Orleans was a vibrant cultural hub. As music bubbled through the city’s wards, Black orchestras performed for Black audiences and tweaked classical tunes in early antecedents of jazz.

That’s the environment where Edmond Dédé came of age. His skill on the clarinet and violin made him “something of a sensation in the city,” according to Keith O’Brien of the New York Times.

That sensational talent brought Dédé shockingly little fame in the world of American classical music. After leaving for France, where he lived and wrote music until his death, he flourished as a composer but never realized his dream: to perform his 1887 magnum opus, a 545-page grand opera called Morgiane. Experts think it could be the oldest existing opera written by a Black American composer.

Now, nearly 125 years after Dédé’s death, Morgiane will finally have its premiere. Staged by OperaCréole and Opera Lafayette, the production is billed as the “the most important opera never heard.”

The story of how the sole surviving copy of Morgaine emerged from an antique music shop in Paris in 1999, wound up in the Harvard music library and finally arrived on stage in early 2025 is nearly as sweeping as the opera itself.

Born a free person of color in 1827, Dédé was required to carry proof of his freedom and struggled to find employment. After a brief stint in Mexico City in the 1840s, he returned to New Orleans to work as a cigar roller. He honed his craft in the evenings, writing poignant songs like “Mon Pauvre Coeur” (“My Poor Heart”) before finally quitting the United States for France in 1855.

“I always say ‘Mon Pauvre Coeur’ is the first blues song,” Givonna Joseph, the founder and artistic director of OperaCréole, tells the Washington Post’s Michael Andor Brodeur. “He wrote it as this wonderful art song, but sometimes I feel like maybe he’s talking about himself. It’s unrequited love.”

Dédé wrote scores for vaudeville productions by day and wrote his opera in the evenings./https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ec/d3/ecd36994-10ff-48d4-85b4-62c27a902064/alhambra_avenue_de_clichy50_impasse_helene_tous_les_soirs_le_centenaire_ballet_inedit_en_1_acte_de_mr_maury_ho_aff811.jpg)

He found greater renown in France, though he was still forced to write opera on the side. To make a living, he conducted in Bordeaux and worked in provincial theaters, producing shows that were “often more like vaudeville than high art,” according to the Times.

“He wanted to be a composer in the art music tradition,” Sally McKee, a retired historian at the University of California at Davis tells the publication. “He wanted to be like Mendelssohn. He wanted to be like Brahms.”

He came tantalizingly close to that goal when he finished Morgiane. It was a fantastical story of a young bride abducted by a villainous sultan, until the bride’s mother—the title character, Morgiane—reveals a shocking secret to help save her kidnapped daughter.

But Dédé never saw it performed. He died with little money a few years later and was buried in a communal grave in Paris. Few people understood—or even witnessed—his great work, bursting at the seams of two bound volumes.

The opera disappeared, and Dédé’s legacy faded into obscurity.

Even his descendants back in New Orleans didn’t realize they had “a relative with that kind of status” until one picked up a magazine in a streetcar in the 1960s and saw a familiar last name, as Wesley Dede told Laine Kaplan-Levenson of WWNO’s “Tripod” in 2018. The composer was his grandfather’s uncle.

But in 1999—nearly 100 years after Dédé’s death—a French music collector sold the manuscript to Harvard’s music library as part of his massive collection of scores. About a decade later, Andrea Cawelti, a music cataloger at Harvard, was still digging through the collection when she came across the Morgiane manuscript.

“I was honestly thrilled because I’ve made it my life’s work to discover things and get them out into the world,” Cawelti tells the Times.

Soon after she digitized the manuscript, McKee published a book about Dédé’s remarkable story called The Exile’s Song. Slowly but surely, Dédé’s legacy was reviving. When Joseph came across the digital manuscript around 2011, she immediately wanted to bring it to life. However, staging a long-lost work comes with unique hurdles.

Parts of “Morgiane,” like out-of-date instrumentation and illegible notes, had to be carefully edited. Houghton Library, Harvard University/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a2/c1/a2c1a5f9-873f-41f3-a01a-d8b3a67a6456/dede_morgaine_p230_231_msharvardhoughton-scaled.jpg)

“There are many challenges, the largest being that the composer has been dead for over 100 years, so we cannot consult with him when we have questions,” Patrick Quigley, the conductor and incoming artistic director of Opera Lafayette, tells WETA’s John Banther.

Some instruments written into the opera’s score, like the ophicleide, are no longer used by modern orchestras. Some sections of the manuscript were near illegible, requiring tough editorial choices on the part of Quigley and Joseph, who collaborated throughout the process of restoring the opera to its intended glory. Last summer, the team began rehearsals in Cincinnati.

“The music is so lush and gorgeous, and [there are] some indications of New Orleans, and it’s perhaps a precursor to jazz,” Joseph tells WGNO’s Christopher Leach.

Kenneth Kellogg, who plays the dastardly sultan, tells WETA that “preparing for Morgiane is no different than preparing for Bellini or Mozart.”

The 1887 manuscript of Morgiane was owned by a Parisian music collector until 1999. Houghton Library, Harvard University/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/50/5d/505d42de-f11e-4573-9751-b3dfe6bef565/dede_morgaine_titlepagebookone_18261860_harvardhoughton-scaled.jpg)

He adds: “What is different, is carrying and reclaiming the legacy of a Black American that was denied the opportunity,” Kellogg adds. “To lend voice to ushering him into the ears and hearts of today’s audiences is a humbling honor.”

After an abbreviated premiere at the St. Louis Cathedral in New Orleans on January 24, Morgiane will greet audiences in Washington, D.C. and New York in early February. Dédé’s original manuscript will also be on view at the Folger Shakespeare Library until March 2 as part of its “Out of the Vault” exhibition.

“It means a lot to me to bring him back home,” Joseph tells WGNO. “We should never allow people to put us in a box. Whatever we are compelled to do, we should do that.”