People living in British America and later the nascent United States recorded their family histories in needlework samplers, notebooks and newspapers

Karin Wulf’s new book, Lineage: Genealogy and the Power of Connection in Early America, explores the many ways in which people of the past reflected on their family histories.

Illustration by Meilan Solly / Images via Karin Wulf and Wikimedia Commons under public domain

Key takeaways: Genealogy in early America

- In early America, local governments, the courts and the clergy collected vital data like births, marriages and deaths.

- But these records weren’t the only tools people used to track their family histories. Americans also memorialized their loved ones through embroidery, oral histories and handwritten texts.

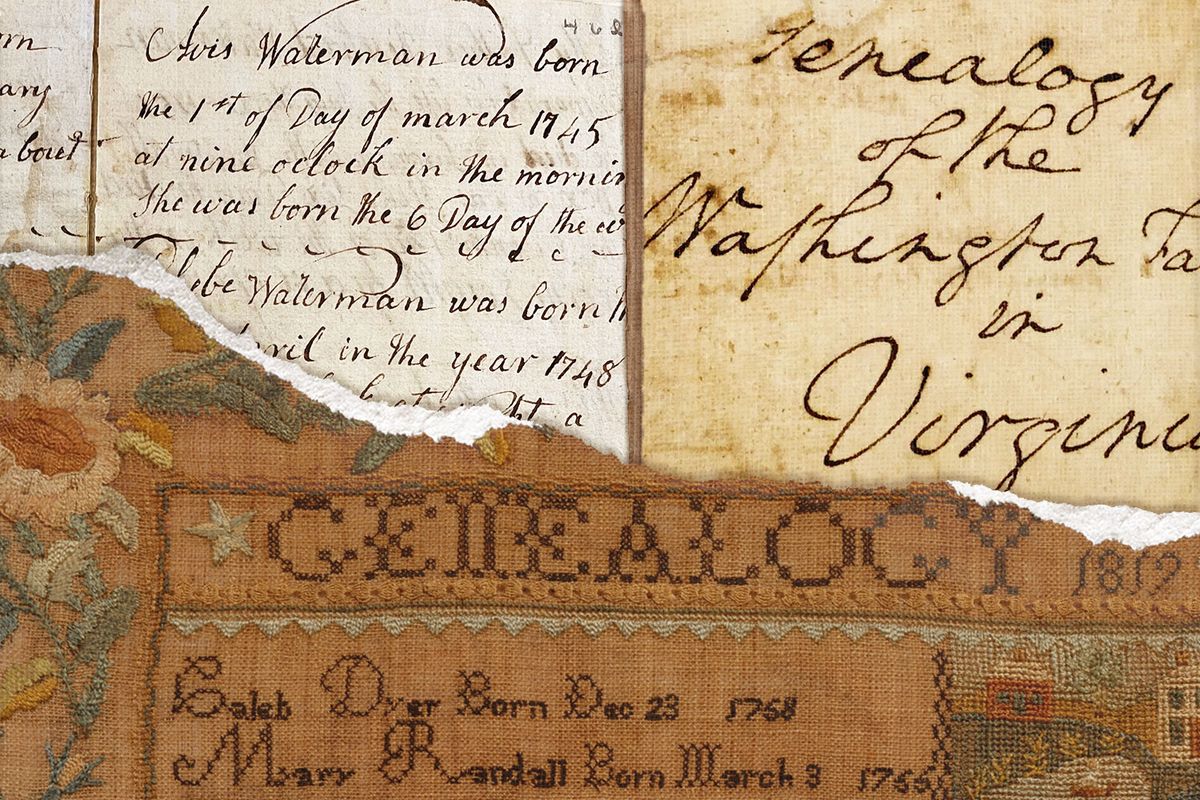

In 1770, when Hannah Waterman was 19 years old, she decided to compile a family history—perhaps because she was feeling very alone in the world. The Rhode Island resident crafted a small, hand-stitched notebook, just 16 pages long, and titled it “Hannah Waterman Her Book.” Into this little book, she copied a family record originally written by her father, Resolved Waterman, recounting his marriage to Hannah’s mother in 1732 and the births of their nine children, one of whom died shortly after he was born.

Hannah was the last of the Watermans’ babies. Born in October 1750, she described the death of her father on the coast of South America before she was a year old: “Departed his life the July the 27th 1751, he died in Suranam [Suriname] with the smallpox.” Hannah noted that her brother Edward died away from home, too, having “sailed in the year 1754 and remains [unheard] of.” Her brother Caleb died in 1762. Then, in 1769, Hannah’s mother; her married sister, Sarah; and Sarah’s young daughter all died within a few months of each other. It was a solemn catalog of losses, this intimate family record that Hannah made.

Pages from Hannah Waterman’s genealogy book, which is housed in the collections of the Rhode Island Historical Society Karin Wulf/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7d/86/7d86e2b5-114b-4301-a4f6-5c951e3c5710/img_6038.jpeg)

Emotional, provocative and even political, genealogy is seemingly everywhere in the 21st century. The hugely popular television show “Finding Your Roots,” hosted by historian and expert genealogist Henry Louis Gates Jr., is now in its 11th season on PBS and regularly reveals the surprising details of celebrities’ family histories. Similarly, media coverage of newly selected Pope Leo XIV’s family background, including by Gates, has been extensive, showing how his family included people of color and grandparents whose love-triangle romance prompted a public scandal.

It’s not only the media that keeps genealogy in front of the public, but also the popularity of investigating family history as an interest and an active pursuit. Launched in 2011, RootsTech, an annual genealogy conference sponsored by FamilySearch, is now both an in-person event in Salt Lake City that draws some 15,000 people and an online event that attracts several million virtual viewers. American family memoirs are an enduring nonfiction genre, too, with new books exploring the complexity of race and immigration gaining wide readership and acclaim.

As popular and pervasive as genealogy is now, it was everywhere in the 18th century, too. For someone like Hannah living in British America, the importance of family history would have been obvious everywhere she looked. Genealogy was stressed in church and in the news. Icons of lineage decorated the landscape in the form of gravestones in cemeteries and the king’s coat of arms on public buildings. Family history was part and parcel of how families operated. So, it would not have been unusual for Hannah to want to keep a record of her own family story. For many people, that record might have been kept orally, but for far more than we might think, a rough little notebook like Hannah’s fit the purpose. These were “vernacular genealogy,” as I call the many different ways that early Americans created records of their family’s histories, in texts and in objects but also using other tools, like oral histories. As I argue in my new book, Lineage: Genealogy and the Power of Connection in Early America, examining the variety and volume of these kinds of genealogies is one way we can understand the importance of family history in this period.

Just as it is today, genealogy was a mix of practical uses and meaningful memory, confirming connections with family near and far, recently or long gone. Family history was interesting to ordinary people and elites alike, including every single founding father. Men and women, as well as younger and much older folks, kept, shared and treasured family records like the one Hannah wrote about the Watermans. They learned about the importance of genealogy in what they read and what they were taught. In girls’ schools in the later 18th and early 19th centuries, for example, family records were a familiar template for learning needlework. Marvelous examples of family history samplers survive in libraries, archives and museums. Presumably, many more are still treasured as heirlooms.

Just as they do today, governments in early America collected family history data, and the media was fascinated by the genealogies of famous people. First the Colonies and then the early American states required, in some fashion, the collection of vital information, like births, marriages and deaths. This kind of data wasn’t systematically or centrally kept and collected until much later, in the 19th and 20th centuries, but we can still see both an interest in and an effort to record family history in this earlier period.

Local authorities and clergymen compiled vital records, which could then be recalled and used by families if they needed to check particular information or by the government for official business. In Colonial New England, for example, residents were eligible for (very minimal) financial relief if they were born in a specific town and fell on hard times. But those who didn’t “belong” in a place, like outsiders and newcomers, could be expelled under a system known as “warning out.”

A sampler created by Mary Hearn in 1793/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e2/28/e2281de4-adb4-4d94-89a9-3644826ddea9/samplers-hearn.jpg)

Genealogy wasn’t limited to government records. Wills and estate papers, inheritance disputes, and paternity cases for babies born to unmarried mothers were just some of the ways that family histories populated court records. When people needed access to family information for legal issues like these, they were sometimes able to use records collected by their local governments or churches. But other times, they brought out their own genealogy records—including needlework.

After the American Revolution, some widows of soldiers who wanted to petition for their late husbands’ pensions submitted samplers as evidence of their family history. Mary Hearn’s sampler, made on the island of Nantucket in Massachusetts in 1793, when she was just 10 years old, became part of her mother Elizabeth’s petition for a widow’s pension.

Modest family histories like Hannah’s book and Mary’s needlework were a form of everyday genealogy that reflected the importance of family connections in British America. But what did media coverage of the rich and famous look like in the 18th century? Almanacs were one of the most purchased types of printed material. In addition to locally practical information like calendars, lunar cycles, roads and court dates, almanacs regularly published the birthdays of the British monarchs and their children. This helped to reinforce the importance not just of those individuals but of the authority that stemmed from their royal lineages.

This statue at Boston’s Old State House features a lion from George III’s coat of arms, passed down from his ancestor George I./https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/77/c0/77c028ed-279e-4062-bae6-455cd4085ea8/old_state_house_boston_w_loewe_9338_20190426.jpg)

In newspapers, happenings from abroad—including announcements of yet more royal births and birthdays—were sprinkled amid advertisements, such as calls for the return of enslaved people and servants running for their freedom. Accounts of royal family relations and their implications for the succession were also carefully chronicled in Colonial newspapers.

When Queen Anne died in 1714, she was the last of Britain’s Stuart monarchs and had no direct heir; a 1701 Act of Settlement had stipulated that to keep the throne in the control of Protestants, the next in line would be a distant German cousin, George I of Hanover. American newspapers throughout the 18th century reported on how these family relationships landed the Hanovers on the throne.

Aside from the royals, the early American media also reported on the tantalizing family histories of the lesser known. They published accounts of remarkable families and individuals, such as a woman who was reputed to be 120 years old and had supposedly “lived to see five of her [family’s] generations.”

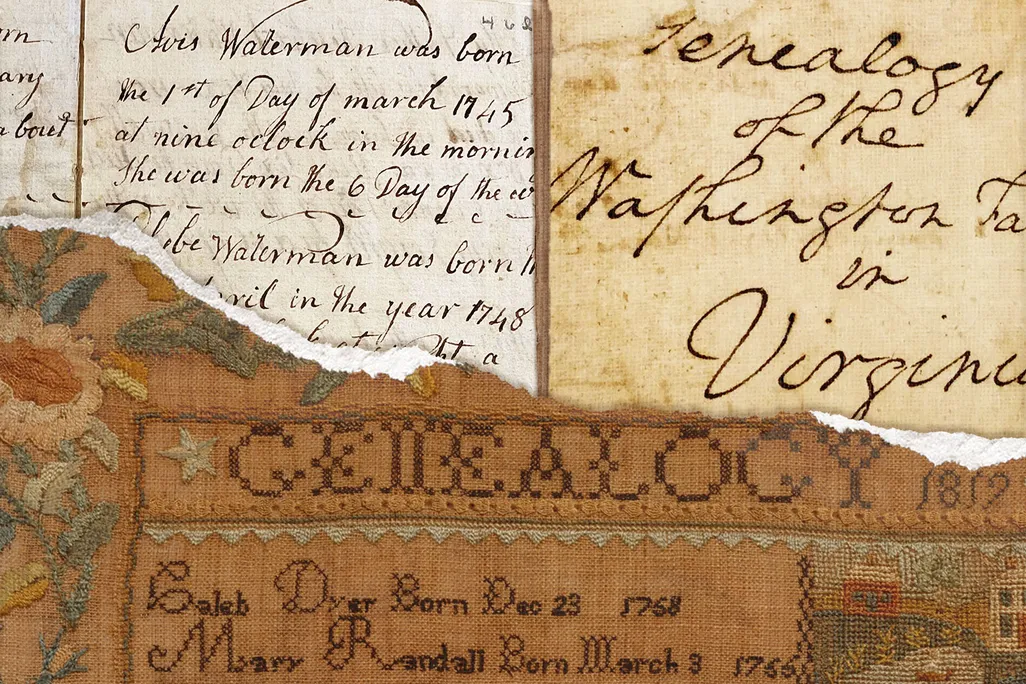

Sophia Dyer’s 1819 genealogical sampler/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/90/4c/904cac4e-6929-4db4-bdd3-70710f76f250/dt7832.jpg)

Some of the most famous names from early America were invested in genealogy: to name just a few, Abigail and John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and George Washington. Both the Adamses and Franklin traced their family histories back to England. Franklin wrote about this in his famous Autobiography, which begins with a comment to his son that “I have ever had pleasure in obtaining any little anecdotes of my ancestors.” That was true, but Franklin’s interest was not quite as casual as his phrasing suggests: He came from a family that regularly conducted in-depth, energetic genealogical research.

While much seems familiar about genealogy’s presence and prominence in early America, aspects of the practice were different, and specific to that time and place. Genealogy was vital to people who were free, for example, but also for enslaved people whose family histories, in a regime of heritable slavery, meant all the difference in the world.

The nation’s first president, Washington, was an avid genealogist who understood how his own family history was intertwined with those who his relatives had enslaved. Although very few of his earliest writings have survived, a single document dating to his teenage years shows just how keenly he paid attention to ancestry and family connection. The future commander in chief wrote out a family tree with five generations of Washingtons on one side of the paper. On the other side, he listed “tithables,” or enslaved people he was inheriting, on whom he would pay a tax to Virginia. Later in life, as others became interested in his family due to his political prominence, he delved even deeper into genealogical work, labeling the paper “Genealogy of the Washington Family in Virginia.”

A family tree compiled by George Washington in his youth/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7e/26/7e26e4d8-d36d-4298-a2ee-5ef9853040b5/master-mss-mgw-mgw4-029-0000-0047.jpg)

Enslaved people in both Washington’s Virginia and British America more broadly also kept careful track of their family relationships. Some of the most prominent examples of these genealogies appeared in court cases in which enslaved people sued to gain their freedom or an enslaver’s heirs contested their manumission. In many of these cases, oral histories of family relationships joined with written records, demonstrating enslaved people’s determination to document their most intimate histories across the generations.

Scholars have only recently started to take genealogy seriously as a historical subject, writing about its importance in different times and places and how, in the United States, genealogical and local historical societies flourished in the 19th century. In early America, however, it was plain that family history was already deeply rooted, a matter of great public as well private interest. Although this world was very different than ours in many respects, the complex ways that public entities like governments collected and deployed those family histories feels very familiar today. Meanwhile, the complexity of family connections, as evidenced by what diverse people across early American wrote, said, stitched or otherwise represented about their families, is simultaneously both very different and very familiar.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.