by NALC Senior Staff Attorney Elizabeth Rumley

Last week, the Trump administration reignited the legal fight over farm animal confinement laws, filing a new lawsuit challenging those in place in California. The complaint, filed by the Department of Justice (DOJ) in the federal district court for the Central District of California, argues that California’s egg rules are invalid under the Egg Products Inspection Act (EPIA)

Challenged Provisions

Specifically, the lawsuit challenges Proposition 12, Proposition 2 and AB 1437, all of which are provisions of California law dictating either living conditions for egg laying hens, the sale of eggs and egg products from those hens, or both.

Proposition 2 is the original California ballot initiative, passed in 2008, imposing specific space requirements for pregnant sows, veal calves and laying hens. Under “Prop 2,” covered animals located in the state of California could not be prevented from lying down, standing up and fully extending its limbs or turning around freely. While numerous other states had previously passed similar farm animal confinement laws affecting sows and calves, this was the first state to also include laying hens.

In 2010, the California legislature followed with AB 1437, a law that imposes those Prop 2 living conditions on egg producers in any other state or country that intended to sell their products in the state of California. Specifically, AB 1437 prohibited shelled eggs from being sold for human consumption in the state of California if the farm or location for production was not in compliance with the California animal care standard.

Later, in 2018, California voters approved Proposition 12, a ballot initiative regulating the production and sale of many veal, egg, and pork products. It combined aspects of the two previous laws, requiring California farmers to provide a minimum amount of square feet to egg-laying hens, veal calves, and breeding pigs, while also requiring that products sold within the state be traceable to animals living in similarly sized areas. The sales provisions of “Prop 12” were challenged in National Pork Producers Council v. Ross, a case that made its way to the Supreme Court of the United States. The Court ruled that the California law was constitutional and allowed it to go into effect. (NALC Explainer here).

Foundation of Current Challenge

In the complaint introduction, the DOJ focuses on its belief that the CA egg requirements are examples of unwarranted regulations that impact consumer cost, preventing farmers across the country “from using a number of agricultural production methods which were in widespread use—and which helped keep eggs affordable”. However, these allegations are more informational, as they are not used or necessary to support the preemption claims.

As far as the legal questions in the complaint, DOJ is claiming that the preemption provisions in the EPIA should prevent California from enforcing the challenged provisions. The EPIA, enacted in 1970, is a federal statute designed to ensure the safety, quality, and labeling of egg products distributed in interstate commerce. The EPIA gives the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) authority to set federal standards for processing, inspection, sanitation, labeling, and packaging of shell eggs and egg products. USDA has done so, for example, by creating a grading and quality system for eggs ranging from AA to B, with a classification system for egg weights, shells, yolks and whites.

Importantly for this lawsuit, the EPIA includes a preemption provision, preventing states from imposing additional or conflicting requirements related to the processing and labeling of eggs that are already covered by federal standards. This preemption is based in the Constitution’s Supremacy Clause, which gives federal law priority over conflicting state laws. (Congressional Research Service preemption explainer here). In other words, once a federal standard is in place under the EPIA, states are barred from enforcing different standards that would apply to the same aspects of the eggs and egg products.

The challenge is primarily focused on the language of 21 U.S.C. § 1052(b). This section has two express preemptions, one focusing on federal standards, and the other on labeling. It prohibits standards or requirements that are “in addition to” or “different from” those imposed by the federal government.

Preemption based on “condition” and “quality”:

According to 21 U.S.C. § 1052(b), when regulating eggs (not egg products) moving in interstate or foreign commerce, “no State or local jurisdiction may require the use of standards of quality, condition, weight, quantity, or grade which are in addition to or different from the official Federal standards”. The “official standards,” according to 7 C.F.R. § 57.1, are the USDA “standards of quality, grades and weight classes for shell eggs”, which are available here.

The limitation, however, is that “the provisions of this chapter shall not invalidate any law or other provisions of any State or other jurisdiction in the absence of a conflict with this chapter.” In other words, if a state or local law attempts to regulate “standards of quality, condition, weight, quantity, or grade”, it will be preempted, but outside of those standards (or others as outlined in the chapter), states are permitted to regulate egg production and sale.

For this part of the complaint, the DOJ focuses on the terms “condition” and “quality,” categories that are expressly preempted by the statute. USDA has defined both terms in 7 C.F.R. § 57.1.

- “Condition means any characteristic affecting a products merchantability including, but not being limited to, the following: The state of preservation, cleanliness, soundness, wholesomeness, or fitness for human food of any product; or the processing, handling, or packaging which affects such product”; and

- “Quality means the inherent properties of any product which determine its relative degree of excellence.”

To support its contention that the challenged laws fall under the definitions for condition or quality, DOJ points to language such as California’s codified “intent” when passing AB 1437. Specifically, that the law is meant to “protect California consumers from the deleterious, health, safety, and welfare effects of the sale and consumption of eggs derived from egg-laying hens.” Cal. Health & Safety Code § 25995. In doing so, the DOJ argues that “AB 1437’s sale prohibition imposes standards of quality and condition on eggs by prohibiting the sale within California of any shell egg that has certain inherent properties—namely, eggs that are “the product of an egg-laying hen that was confined on a farm or place that is not in compliance with [California] animal care standards” (Complaint, at 58).

As for Prop 12, the DOJ argues that it “prohibits the sale of eggs with certain inherent properties or qualities that purportedly affect such products’ degree of excellence, wholesomeness, and fitness for human food. See Proposition 12 § 2 (‘The purpose of this act is to prevent animal cruelty by phasing out extreme methods of farm animal confinement, which also threaten the health and safety of California consumers, and increase the risk of foodborne illness[.]’)” (Complaint, at 61).

These arguments are attempting to establish that the AB 1437 and Prop 12 space requirements for the birds fit the definition of either a “condition” or “quality” standard for the eggs. If so, this would trigger the express preemption within that statute. After which the question will be whether the standard is additional to or inconsistent with the federal requirements. There are no federal requirements governing the living space required for laying hens.

Preemption based on labeling

The DOJ also argues that the challenged laws violate the labeling provisions of 21 U.S.C. § 1052(b). This section mandates that “[l]abeling, packaging, or ingredient requirements, in addition to or different than those made under [the EPIA], the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act [21 U.S.C. 301 et seq.] and the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act [15 U.S.C. 1451 et seq.], may not be imposed by any State or local jurisdiction, with respect to egg products processed at any official plant in accordance with the requirements under this chapter and such Acts.” Note that the labeling preemption provisions apply to egg products, but not to shell eggs.

For this argument, they first rely on California regulations implementing the two laws, noting specific language requirements for documents of title and shipping manifests. In order to succeed here, they will have to convince the court that shipping documents fall under the category of “labeling, packaging, or ingredient requirements” before the court could move on to the next question.

Next, the DOJ highlights 3 Cal. Code Regs. § 1320.4(c), which states that “[n]o person shall label, identify, mark, advertise, or otherwise represent shell eggs or liquid eggs for purposes of commercial sale in the state using the term “cage free” or other similar descriptive term unless the shell eggs or liquid eggs were produced in compliance with section 1320.1 of this Article.”

In order to succeed here, DOJ would have to first convince the court that this is a “labeling, packaging, or ingredient” requirement, and second that it is a requirement different than or in addition to those imposed by USDA. USDA labeling guidelines define “cage free” as “laid by hens that are able to roam vertically and horizontally in indoor houses, and have access to fresh food and water. Cage-free systems vary from farm-to-farm, and can include multi-tier aviaries. They must allow hens to exhibit natural behaviors and include enrichments such as scratch areas, perches and nests. Hens must have access to litter, protection from predators and be able to move in a barn in a manner that promotes bird welfare.” Compliance with these regulations is verified by either USDA or a third party certifier. California’s requirements are similar, but not identical. They include specifications as to the minimum amount of floor space required, and also require verification by a third party certifier approved in the state of California.

Next steps:

As this challenge was just filed on July 9th, the court has not yet begun to consider the issue. The DOJ has asked a judgment declaring that each of the challenged laws and accompanying regulations are expressly preempted, and preventing the state of California from enforcing them. The next step most likely be a response to the complaint by the state of California, although it is also possible that a request for an injunction to prevent enforcement might enter into the timeline.

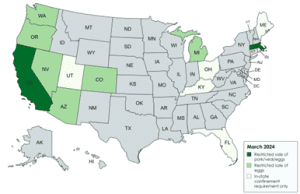

It is also important to note that California was the first state to regulate in-state sales of products from non-conforming ag operations, but it is not the only one who has chosen to do so. Since AB 1437 was passed, several other states have followed suit, typically requiring that only “cage-free” eggs be sold within their boundaries. A ruling in this case would affect requirements in those states as well. California and Massachusetts are the exceptions, requiring compliance with pork and veal, as well as eggs. A ruling in this case would only affect the egg and/or egg products provisions of California’s and Massachusetts laws.