This is a two-part series looking at airline credit cards. Today, we look at how it all works. Then tomorrow, we’ll ponder what happens if it all goes away.

The airlines in the US have developed into a special kind of company… one that consistently loses money on its core business but makes up for it on financial services. This is thanks to the way banking laws work in the US. Cobranded credit cards have been an absolute gold mine for the largest airlines, and as of now, there is no end in sight.

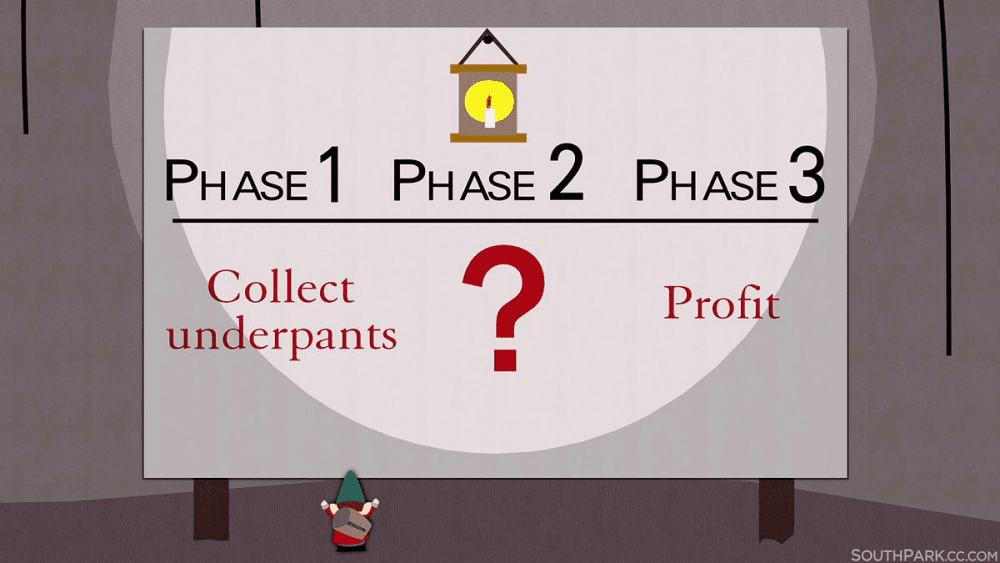

The way it works today is surprisingly not that complicated on the surface. Allow me to post an image that simplifies it for you.

I kid, I kid. But it isn’t actually that complex at a high level. Airlines partner with credit card companies so they can both make money on these cobrand deals. You have Delta and Amex, both United and Southwest with Chase, American recently consolidating its relationship with Citi, Alaska with Bank of America, and JetBlue with Barclays. Those are the biggest ones, at least. But every airline has one. Avelo is with Capital One, Breeze is with Barclays, Allegiant is with Bank of America, and so on. Foreign carriers have them too, though most won’t get as much traction with US-based customers, and regulations at home make them much less lucrative.

The credit card companies charge an annual fee to the cardholder, and of course, there is an extortionary interest rate for those people who don’t pay their balances on-time. Then, the big money is made every time the cardholder uses a card. If you’ve ever accepted a credit card as a business, you’ve probably seen things like “2.9 percent plus $0.30 a transaction.” That’s a pretty typical arrangement. So if you sell something for $100, you’ll only collect $96.80. The rest of that money gets split up in a million ways.

Some of the fees are called merchant service fees and go to the business’s payment processor and gateway. Others — interchange fees — go to the bank of the cardholder. And then there is money that goes to the network. (Think… Visa, Mastercard.)

Sometimes businesses sign up for flat rate pricing, but those are padded to make sure that the card companies do well. Others have variable rates with fees that can fluctuate greatly depending upon the type of card, what information is provided upon purchase, whether the card is present for the transaction or not, etc. Basically, the banks are charging more when they have to pay out more and when they are concerned about fraud. In the end, an airline rewards card will have a higher interchange fee, because the rewards can be costly.

So, where do these interchange fees actually go? They go to the bank that issued the card, but the bank has to make sure it has attractive cobrand partners or people won’t use the cards. Airlines are very attractive, and they have become the most important partners because they can award miles when people spend on the card.

There are requirements around marketing and advertising and all that, but the primary transaction that occurs is that each time someone buys something, that person earns points with the airline that’s named on the card. You spend a buck, you earn a point… or whatever the ratio is at each program. And when you earn those points, the bank actually buys them from the airline using all those hefty interchange fees (and other sources of revenue). Whether it’s a penny a point or something else, this adds up very quickly to big, big money for the airline.

It’s also money that has saved airlines during the lean times. For example, American Express prepurchased $500 million worth of miles from Delta in 2004 to help it avoid bankruptcy… for almost a year before it filed anyway. That’s a pretty nifty little trick.

This is, of course, not just something that airlines can do. There are hotels, Amazon, Home Depot, the Gap, pretty much any place you might shop that has a card available. Heck, even your alma mater probably has a terrible credit card that it hopes you’ll get out of loyalty. And of course, there are cards that aren’t branded that just give you cash back instead of rewards. But nothing matches the size, power, and appeal of the airline cards.

The most important relationship these days is between Delta and American Express. Ever since Costco left Amex, Delta has been by far the largest airline partner for Amex. Without Delta, Amex is in big trouble. And Delta, for its part, netted more than $7 billion 2024 from the deal. It expects that to grow to $10 billion a year. That is a lot of miles.

As Courtney Miller noted in his recent Visual Approach newsletter, that swung Delta from a -2.5 percent operating margin to +10.5 percent. In fact, not a single one of the big airlines would have been profitable in 2024 without that money, though United got closest hitting a mere -1.9 percent operating margin.

While this all sounds great, there are downsides. The fees are higher to support this system, naturally. And this is really an unfair playing field, because the biggest airlines are far more attractive to a credit cardholder. The opportunities are just greater, and that means the little guys get cut off at the knees once again. That hasn’t stopped them from trying, but they are at least somewhat realistic.

On Frontier’s Q4 earnings call, Chief Commercial Officer Bobby Schroeter said this:

Loyalty remains a significant financial opportunity. Today, our co-brand revenue per passenger is under $3, compared to over $30 at legacy and other low-cost carriers. Even capturing a fraction of the legacy and low-cost carrier levels represents a meaningful and achievable growth opportunity over the next few years.

This means that the big airlines have yet one more advantage that keeps them where they are. That I will talk about more tomorrow.