Ten years ago, craft beer fans couldn’t have imagined “line life” referring to anything other than the hourslong queue for a brewery’s latest limited release. Today, however, it could very well describe the supermarket checkout line. As craft beer fades from shiny new toy into just another everyday beverage option, more beer drinkers are getting their IPA and stout fixes from the same place as their cereal and hummus. And in a growing number of supermarkets, that beer is from a store’s own brand.

The popularity of grocery stores’ private-label beer brands—that is, cans and bottles with store-brand labels, but brewed by a contract brewer—is on the rise: Per Brewbound, sales of these grew by 122 percent from 2023 to 2024. Aldi, whose overall inventory is 90 percent private label, has doubled its beer portfolio to 16 SKUs—plus seasonal additions—in the last two years, and sales have grown over 100 percent. And, according to speculative reports, Walmart, the country’s largest grocery chain, is working on its own brews.

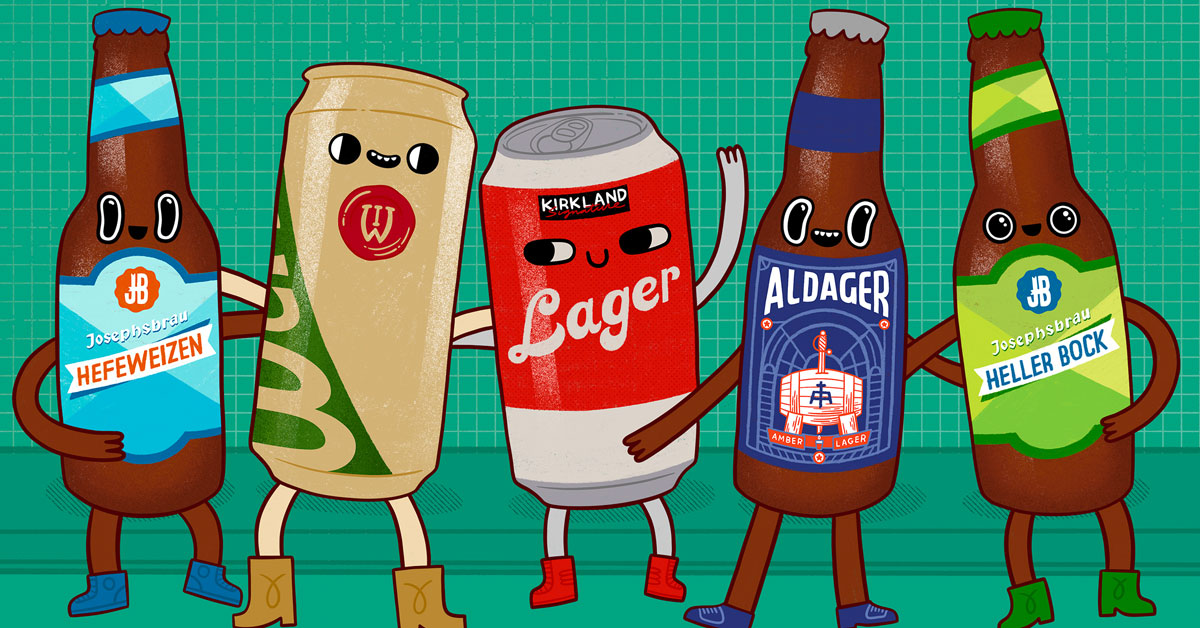

Aldi’s lineup includes beers with names and label designs that could come from any local brewery: Wernesgrüner Pils, Wild Range Brewing Company IPA, White Tide Wheat Beer. At Trader Joe’s, customers can get the store’s own Drive Thru Red Dry Hopped Red Ale, Stockyard Oatmeal Stout or Boatswain IPA—American, double or hazy—under the store’s brewery simulacrum, “Josephsbrau.” Costco has offered beers through its Kirkland Signature brand (which also sells spirits) off and on over the years, but seems to have finally struck gold in fall 2024 with a helles-style lager; it’s been met with rave reviews thanks to the fact it’s actually repackaged Prinz Crispy, a Great American Beer Festival gold medal winner from Oregon’s Deschutes Brewery.

As for the beers themselves, overall, among craft beer drinkers, they’re getting mixed feedback. “The Wernesgruner Pilsner is surprisingly good for the price point,” says one Reddit user. On an “Aldi Aisle of Shame” Facebook post, a commenter calls that very pilsner “the only beer worth buying,” while another says all Aldi beers seem milder than those from other breweries. One Redditor casts Trader Joe’s entire lineup as a no-go, while yet another thread is dedicated to mourning the discontinuation of the store’s (vaguely racist?) Trader José Mexican-style lager. Meanwhile, Reddit threads reveal Costco’s co-branded Deschutes lager has won beer-fan cred with shoppers excited about its high quality.

But why are grocery stores leaning into private-label beer in the first place? Part of it, it seems, is that consumers seem more receptive to it than ever.

“Private label is a proven strategy for grocers: high-margin, high-trust and increasingly consumer-preferred,” says Theodore Schweitz, CEO of CPG networking company Drive Wheel. He says that beer, “a category that’s become bloated and bewildering to consumers,” was prime for the private-label treatment. Retailers have an incredible amount of data on what their customers buy, Schweitz adds, so they can cut through the noise with what their shoppers want and how they want it. Case in point: Aldi has a team dedicated to tracking consumer preferences, according to Arlin Zajmi, the company’s wine specialist and director of national buying for adult beverages. That team collaborates closely with Aldi’s beer and wine suppliers to oversee recipes.

Private-label sales are the result of a perfect storm of consumers tightening their belts in the face of an inflation-burdened economy, grocery stores having the resources to zero in on exactly what shoppers want, and the fact that customers trust their go-to stores to deliver quality. Beverage reporter Kate Bernot cites similar private-label offerings in every category, from food and drink to beauty products. “There are dupes from grocery store and drugstore brands, and TikToks saying ‘This drugstore-brand lip gloss is just as good as Fenty.’” It’s become more socially accepted than ever to bargain-hunt—why spend more if you don’t have to?

At a New York Costco, a 12-pack of Kirkland Signature Helles-Style Lager is $15.69. Deschutes doesn’t sell Prinz Crispy under its original label anymore, but its King Crispy Pilsner is $9.50 for a sixer, so $19 for 12 cans. The difference isn’t earth-shattering, but it’s not nothing. It represents a compromise for consumers who want the taste of craft beer, but wouldn’t mind saving a few bucks.

“Young drinkers don’t see craft as a different category, I don’t think. To them, beer is beer.”

Stores, too, are becoming more transparent about who brews their private-label beers—facts that used to be a (poorly kept) secret; Aldi is now open about its partnerships with contract brewers Octopi Brewing and Genesee Brewing Co. as Costco is with Deschutes, and that’s part of the draw for devout craft beer fans.

“What initially drew my eye to the Kirkland lager was that it was brewed by Deschutes,” says Isaac Bell, a Washington, D.C.–based pitmaster and beertender. “And that it was a helles lager. One of my favorite styles, brewed by a craft brewery that is part of the Brewers Association… At less than $1.25 a can for the Kirkland lager, I’ve got Crispys in the fridge all day long.”

For upstate New York beer writer Will Cleveland, these grocery store beers offer an opportunity for discovery that drives craft enthusiasts. In particular, he’s a fan of Deschutes’ Costco lager; Mountain Brew, a lager by Paradox Brewery for convenience store chain Stewart’s; and Locken’s Ruby Grapefruit kölsch, brewed by Genesee for Aldi. He also shops at Wegmans, which sells store-exclusive beers, like Other Half’s Astor Place hazy IPA; it’s a dollar or two cheaper than the brewery’s other hazies.

Others attribute this rise to choice—too much of it. Beer writer and author Jeff Alworth recently wrote that craft beer is in its “wallpaper phase”—as in, craft beer is just there now, in the background, another beverage option. “Young drinkers don’t see craft as a different category, I don’t think. To them, beer is beer,” he says. “Modelo or a local IPA? Beer.” When customers don’t consider local, independently made beer special, he adds, they’re less willing to pay a premium.

As the craft beer market has changed, the breweries that have best weathered the shift are the ones that meet consumers where they are, and use what they know about today’s drinkers to adapt. Ultimately, grocery store chains—with budgets exponentially larger than any craft brewery’s and entire teams dedicated to applying data to product development—are nailing this, courting craft beer fans and more mainstream drinkers alike.

“When beer looks so overwhelming, there’s something very appealing about picking something easy,” says Bernot. “We forget that’s the way so many people shop: Whether it’s Kirkland beer or Twisted Tea, they’re going for the thing that’s known, easy and clear,” like a can that simply reads Lager, front and center.