I spent all of my mornings this past week writing about sound in video games, and in the process, I kept coming back to the Nintendo GameCube, which led me to think in particular about gaming in the early 2000s, since the GameCube debuted in 2001.

My subject was, and remains currently, the contemplative aspects of video games and video game sound, notably when one is encouraged — or acts on the instinct — to pause without hitting pause, to situate oneself in a virtual space and observe, especially by listening, to the digital world in which one and one’s on-screen counterpart(s) are engaged. Think of this practice as gaming transcendentalism. In our time of highly popular long-form gaming videos that document digital environments, it’s a fascinating subject that brings media archiving into the realm of the somatic.

Throughout this writing I’ve been doing, an inevitable reference point, for me, has been Cory Arcangel’s classic media art piece, the deeply reflective Super Mario Clouds, which he created in 2002 (and which was featured two years later in the Whitney Biennial). This despite the fact that Super Mario Clouds is, in fact, entirely silent.

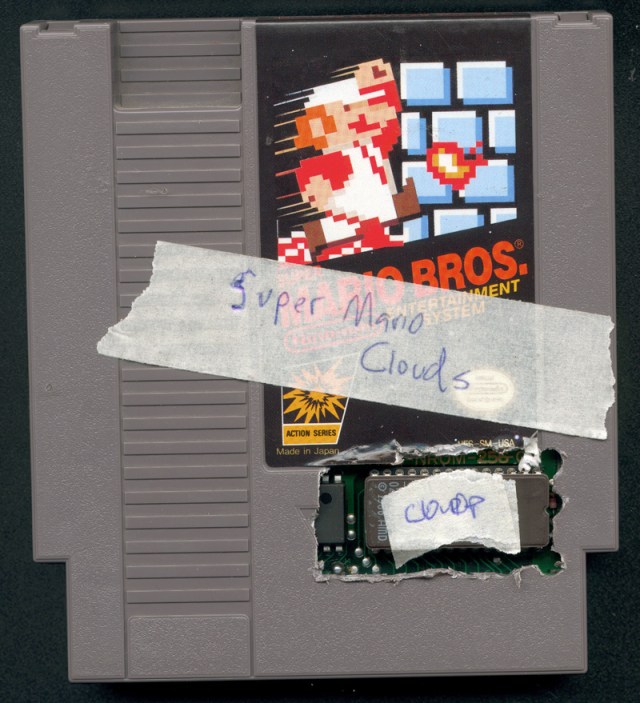

For the work, Arcangel took a cartridge of the game Super Mario Bros. and hacked it to remove everything but the blue sky and the cartoonish white clouds. Absent are Mario, and his various obstacles, and even Koji Kondo’s musical score. All that remains are a static sky and those passing clouds, which tellingly resemble thought balloons.

Super Mario Bros. ran on the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), aka the Family Computer (Famicon), and was the very first Super Mario game. It came out in 1985, two years after the NES debuted. What may be useful to note is that Arcangel was born in May 1978, so he was about seven and a half years of age when Super Mario Bros. appeared. An impressionable phase of one’s life, to say the least.

While reading up on the topic, I checked out, among other resources, the Whitney Museum’s archive, its online catalog, video of Super Mario Bros. gameplay, and the Whitney page for the Arcangel work, which includes the following description and question:

“By tweaking the game’s code, the artist erased all of the sound and visual elements except the iconic scrolling clouds. On a formal level, the project is reminiscent of paintings that push representation toward abstraction: how many elements can be removed before the ability to discern the source is lost?“

And then I made my way to Arcangel’s own website, which has a page dedicated to Super Mario Clouds, displaying his hacked cartridge — and including a link to his own version/remix of the original Super Mario Bros. software.

I downloaded the Zip file, de-archived it, and recognized the file’s suffix, .nes, from the ROMs for old NES games. We live in the golden age of cheap small portable game consoles that allow one to play outdated video games, so on the chance it might work, I popped the microSD card out of my Anbernic RG35XXSP, a small, clamshell device that pointedly resembles a Game Boy Advance SP. I put the SD card into my laptop, dragged the .nes ROM (file name: arcangel-super-mario-clouds.nes) into the folder titled FC (for Famicon), safely ejected the microSD card, and slid it back into the slot on my SP.

On his website, Arcangel notes that Super Mario Clouds remains, to some degree, a work in progress: “I still need 2 get around 2 cleaning up all the different versions of this code.” So, I wasn’t even sure if his ROM would run, or if it might even freeze up my SP. I turned on the Anbernic, found my way through the menus to the arcangel-super-mario-clouds.nes file, and hit play — and it worked, immediately. The screen turned blue as the brightest day of summer, and the little white clouds began to pass by slowly from right to left.

The dimensions of the image, however, left wide black spaces on either side of the screen, and I recalled that Arcangel’s site had a note that read “Dims: Dimensions variable.” Taking that allowance as a cue, I went through the menus in the alternate firmware I’d installed on my Anbernic SP (in essence, I was running modded software on modded firmware), made a few changes to the arcane settings, and Super Mario Clouds proceeded to fill the screen from edge to edge.

This is when I had the urge to record a long, continuous segment, 10 minutes, to share online. Though Super Mario Clouds is, of course, itself silent — the absence of sound being one of myriad ways Arcangel chiseled his work from larger, more complex source material — that silence speaks to the contemplative opportunities inherent in video games.

I also recalled that game designer Shigeru Miyamoto, creator of Super Mario, had, early on in his work at Nintendo, been tasked with finding a creative reuse of thousands of abandoned arcade consoles originally designed for a failed game called Radar Scope (1980). In Radar Scope, the screen shows an image that goes off toward a distant horizon, providing a sense of three-dimensional play. Miyamoto dispensed with 3D, and embraced the creative constraint of merely two dimensions. The result was Miyamoto’s first classic (of many), Donkey Kong (1981). There’s a connection to be drawn between Miyamoto’s reduction of the arcade game format to two dimensions, and Arcangel’s further reduction of Miyamoto’s original Mario game to merely its backdrop.

Now, on the one hand, my video of Super Mario Clouds on a modern handheld is, like Arcangel’s original work, entirely silent. On the other hand, the piece’s elegance and its (virtual) environmental focus make it part and parcel of the gaming transcendentalism that I happen to explore mostly through video game sound. To reinforce this point, I almost edited my video to a length of 4 minutes and 33 seconds, following John Cage’s template, but then I decided that 10 minutes allowed for a more immersive experience.