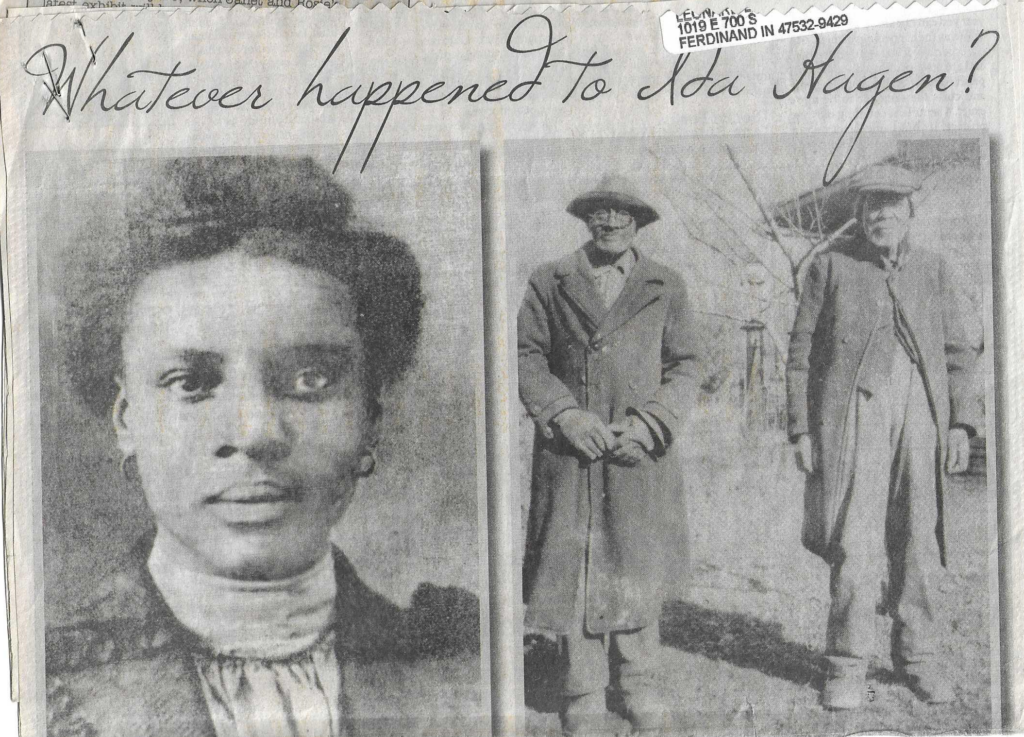

Her name might not be in Who’s Who Among African Americans, or have household recognition like Madam C.J. Walker, but Ida Hagan broke barriers not only for her race, but her gender. From a young age, Hagan bore the burden of being the only Black person in the room. Perhaps this garnered the tenacity required of her in 1904, when her appointment as deputy postmaster of the post office in Ferdinand, Indiana drew intense local resistance and national attention. This would only be the first stop on her professional journey, and she would go on to become a pharmacist and labor union organizer.

Born May 24, 1888, Ida Priscilla Hagan grew up in the Pinkston Settlement, a free Black settlement west of Ferdinand. It was founded in the mid-1800s by her great-grandfather, Emanuel Pinkston Sr. In 1897, the Huntingburgh Argus wrote that “There are 5694 white children in the district schools of Dubois County and our little colored girl whose name is Ida Hagan. Ida is eight years of age and is a pet pupil in District No. 4 in Ferdinand Township.” She graduated with honors from the Gehlhausen School in Ferdinand Township in 1902, with the Huntingburgh Independent claiming that she was “the first colored pupil in Dubois county [sic] to graduate from the district schools in this county.” Hagan was also reportedly the first Black resident in the county to attend a public high school, Huntingburg High School.

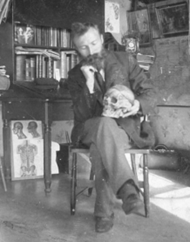

Her life would change when she met Swiss-born Ferdinand physician, Dr. Alois Wollenmann. After his wife, Fidelia, died during childbirth, he hired Hagan to help care for his two sons and assist in his drug store, the Adler Apothak. The store also served as the town’s post office, of which Dr. Wollenmann was postmaster. Hagan remained with the Wollenmann family during the week, and on the weekend she would return to the Pinkston Settlement. In 1904, at age 16, he appointed Hagan deputy postmaster.

While her age might have been controversial enough, there was one particular detail about Hagan which might have been more important: she was a Black woman. According to historian Justin Clark, Dr. Wollenmann made the bold and courageous decision to appoint Hagan at a time when racial terror lynchings were regular occurrences and Jim Crow was bifurcating the country. The doctor stuck by his decision, saying that it was “his own business” whom he appointed as his assistant and she would “remain as assistant as long as he is postmaster in Ferdinand.”

It was unclear to residents and newspaper editors around the state why Dr. Wollenmann appointed a Black girl, despite receiving job applications from white girls. Threats were made to burn the doctor in effigy and boycott his office, but the doctor did not seem alarmed and showed no inclination to yield to the “unwarranted prejudices” of critics. The English News on August 19, 1904 noted of the appointment “The patrons of the office are much incensed at the appointment of a colored person for assistant, and especially since the lady was not even a resident of the town.”

The Logansport Daily Reporter noted of Hagan:

In an interview she said that people were glad to see her working in their houses and she cannot see why they object to her working as a deputy in the post office. She said that if she had known her appointment would have the storm that it has, she would not have accepted, but that now she will hold on to it, and the doctor will keep her, she does not propose to be driven out if she can help it.

Nevertheless, Hagan withstood the pressure and excelled at her job, endearing herself to the community with her efficiency, kindness (especially for the infirm and elderly), and ability to speak the Low German spoken by many of the locals.

While working at the store, and under Dr. Wollenmann’s tutelage, Hagan took a home study course in pharmacy offered by Winona Technical Institute, the precursor to Butler University. She received her Indiana pharmacy license in 1909. She was just 20 years old, an accomplishment for anyone that young, let alone a Black woman. According to John Clark (Assistant Professor at the College of Pharmacy, University of South Florida), Keenan Sala (Indiana State Archivist), and Dr. Gregory Bond (Assistant Director of the American Institute of the History of Pharmacy), Hagan became the first known licensed female Black pharmacist in the state and likely the youngest in the nation.

Hagan could certainly be described as a trailblazer in the field of pharmacy, joining Harriet Marble, Julia Pearl Hughes, and Anna Louise James as some of the first Black women in pharmaceuticals. These young women were privileged and attended schools like Howard University, Meharry Pharmaceutical College, Brooklyn College, among other notable universities. Hagan, however, took home study courses while working at the drug store and post office, and caring for Dr. Wollenmann’s children.

On October 17, 1903, tragedy struck when Dr. Wollenmann fell ill with tuberculosis. In an attempt to heal, he temporarily left his sons in Hagan’s care and returned to his native Switzerland to recuperate and visit with his sister. In his absence, he reappointed Hagan deputy postmaster to manage duties. However, just weeks after his return to Ferdinand, he passed away at the age of 48. Upon his untimely death, Hagan became acting postmaster, one of the first Black women in Indiana to hold this position. The Indianapolis Recorder noted on July 27. 1912 “Ida’s honesty and integrity has won the respect and confidence of the community in which she lives and the position tendered her is a tribute paid not only to Miss Hagan, but to the race.”

Hagan held the position until she resigned weeks later, possibly stemming from her impending marriage to Alfred Roberts, a typesetter for the Indianapolis Recorder. Ida joined Alfred in the capital city, where she began her new life as a pharmacist at the Eureka Drug Store on West Street.

In 1915, Ida Hagan Roberts moved to Gary, accepting a position as a pharmacist for Dr. Arthur Adams who had just opened The Adams Pharmacy. The Recorder published an article about the new store, stating:

This is a pleasing, and remarkable Race Enterprise, in which the colored citizens of Gary, should be very proud of indeed, and not only the citizens of Gary, but those citizens of Chicago who visit Gary frequently and who have been segregated by white people in seeking a place for refreshments, and which you and your friends are always welcome. . . . Dr. Arthur is a well-known citizen in not only Gary, but through the state, and is worthy of the support and confidence of every race loving Negro.

In 1925, Ida filed for divorced from Alfred Roberts, and on September 29, 1926, she married Sidney Whitaker, a railroad porter working for the Pullman Company, and moved to Detroit. He is likely the reason she became involved with the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), founded in 1925 by the elder statesman of the Civil Rights Movement, A. Philip Randolph. BSCP was the first predominantly-Black labor union, composed of highly-educated porters and maids hired by George Pullman to work on his sleeping cars. Pullman workers were expected to work long shifts for low pay and in poor working conditions, especially compared to white workers. The BSCP challenged these inequities.

Six weeks after the union was founded, wives and relatives of porters formed the BSCP Ladies Auxiliary. These women became labor conscious activists, demanding consumer, and workers’ rights. They were credited with helping to make the BSCP the first successful national Black trade union in the nation. Ida served as president of the Detroit Division of the Ladies Auxiliary of the BSCP, which generated financial support and advocated for public policy measures, such as grade labeling of canned food products. She was involved in the Auxiliary until the 1950s, when the rise in ownership of private automobiles, improved air transportation, and construction of interstates minimized the need for railroads.

At the age of 76, Ida continued to lobby for equal rights. John Dotson, Pulitzer Prize winning writer for the Detroit Free Press, reported on March 10, 1965, that she joined 10,000 protesters in Detroit, marching in solidarity with those in Selma, Alabama agitating for Black voting rights. She summoned her BSCP Auxiliary friends to join her in the local march, telling the paper “’I just hope and pray that this is an awakening for those who don’t know what we’re up against.’” Ida Whitaker joined college students, who cut class to attend the orderly march. The paper summarized:

Detroit’s [march] wasn’t like the ‘glorious day’ of the March on Washington, but you got the feeling that this one meant more.’ Ida remained active in civil rights, religious and civic causes the remainder of her life. She saw results from her hard work and was quoted as saying, ‘It’s better to wear out than to rust out.’

Ida (Hagan) Whitaker died on February 8, 1978, and was buried alongside her husband, Sidney, at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Detroit. The Detroit Public Library was unable to locate obituaries for either of them. After an intense search for an obituary in all available Detroit newspapers, and with the help of many different sources, it is questionable that their obituary was ever published. The Michigan Death Records provide only the date of her death. She was childless, her brother never had children and he preceded her in death, so no one was left to tell her story.

No one, that is, but us.

On Saturday, May 31, 2025, the State of Indiana will honor Ida Hagan Whitaker with a Historical Marker, to be installed in Ferdinand, at the former site of Dr. Wollenmann’s Adler Apothak and the Ferdinand’s Post Office.

Sources Used:

Databases

Ancestry.com

Hoosier State Chronicles

Newspapers.com

Experts/Advisors:

Dr. Gregory Bond, National Institute on History of Pharmacy

Dr. John Clark, University of South Florida, Pharmacy

Rosemary Stewart

Eric Uebelhor

Newspapers

Detroit Free Press

Detroit News

Detroit Tribune

English Times

Ferdinand News

Indianapolis Recorder

Jasper Herald

Logansport Pharos

Organizations

Christ the King Catholic Church, Detroit

Detroit Catholic Archdiocese

James Cole Funeral Home

Michigan Dept. of Licensing & Regulatory Affairs

St. Benedict Catholic Church, Detroit

St. Frances D’Assisi, Detroit

St. Rita’s Catholic Church. Indianapolis

Repositories

Butler University

Detroit Public Library (Burton Historical Collection)

Dubois County Museum

Indiana Historical Society

Indiana State Archives & Records Administration

Indiana State Library

Indiana University Indianapolis University Library

Jasper–Dubois County Public Library

Lake County Public Library

Michigan State Archives

Michigan State Library

Plainfield-Guilford Township Public Library

Secondary

Melinda Chateauvert, Marching Together: Women of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1998)

Gary Alan Fine, “The Pinkston Settlement: An Historical and Social Psychological Investigation of the Contact Hypothesis,” Phylon 40, no. 3 (3rd Quarter, 1979): 229-242, accessed JSTOR.org

Misc.

Imelda (Uebelhor) Becher’s Scrapbook

Indiana Bd. of Pharmacy

Michigan Bd. of Pharmacy

Michigan Chronicles

Michigan Death Records

Midwest Druggist