John Womack Jr.’s Labor Power and Strategy, published by PM Press in 2023, offers a blueprint for how workers can leverage their latent power and expand the labor movement’s influence and numbers. The book was released before the decidedly anti-labor Trump administration took office in Washington, D.C., started dismantling the infrastructure of the federal government, and threatened to abandon or betray America’s long-term overseas allies. With an existential crisis seemingly at hand, some might think that the issues raised in Womack’s book are suddenly of secondary importance. But to surrender to despair or inaction would be shortsighted. Regardless of the immediate challenges, labor advocates must always consider strategies to improve the lives of working people through unionization. The struggle for social justice continues.

Labor Power and Strategy focuses on two lengthy 2018 interview sessions with Womack conducted by retired ILWU Organizing Director Peter Olney. Womack is a distinguished Harvard professor emeritus of Mexican history. Glenn Perusek, a long-time union researcher and a colleague of Olney’s—both taught organizing classes at Michigan State University—transcribed and edited the interviews. Ten veteran organizers and academics with labor interests or experience analyze and comment on Womack’s “Foundry Interviews,” named for a restaurant in Somerville, Massachusetts, where the original interviews were recorded. Womack then responds to the points raised by the ten commenters.

Professor Womack contends that because any modern industry or company is composed of several linked technologies and other key entities, there are multiple places where workers can obstruct business operations to win an organizing drive or a strike. These “choke points” differ in various businesses. Wherever technology or other operations interface, he insists, “like at a dock, at a warehouse, between the trucks and the inside, between transformers and servers and coolers, there can be a bottleneck, a choke point.” Organizers and workers, his argument goes, have to identify these intersections as company weaknesses that can be exploited to interrupt production and reinvigorate and expand labor’s numbers and strength. (In assessing Womack’s proposition, recall that the 2018 Foundry Interviews were recorded before the Covid 19 epidemic, the tentative revival of the American labor movement in the early 2020s, and the promising results of “Solidarity Summer” in 2023.)

Womack has many additional things to say during the Foundry Interviews. He feels that indirect power, or “associational power,” such as “appealing to popular morality or indignation for mass support,” is usually of marginal importance compared to strategic worker force as he outlines it. Womack concedes that associational power can help in a crisis, but insists that without real force “all you get is association in action, movements, which in their heyday may be inspiring, but continually, always fade. Only with material power—not with it only, but only with it, on its strength—can you force change and keep it.” He looks at increasing worker organization along global supply chains in basically the same way that he looks at increasing worker power generally. Before effective action is feasible, he says, it is necessary for labor to study “the industrially and technically strategic weaknesses in the chains.” Ultimately, he asserts, “unless you have the power of disruption, you can’t realistically develop any strategic plan.”

It follows from this reasoning that Womack expresses little faith in the long-term organizing chances of isolated gig workers or little groups of Starbucks servers in single shops. For Womack, workers in a position to meaningfully block production and seriously reduce employer profits remain the key to real working-class power. Along the way, Womack criticizes the Democratic Party for not being more directly helpful to workers who are not represented by big unions and also criticizes major unions for not doing more to help the working class in general.

Bill Fletcher, Jr., the prominent labor activist and writer, is the first to comment on the Foundry Interviews. After registering concern that automation and robotization threaten to weaken the utility of Womack’s proposal, Fletcher argues that Womack’s analysis itself misses the important roles of race and gender in developing any plan to strengthen labor’s cause. Dan DiMaggio, an assistant editor at Labor Notes and a former student of Womack’s at Harvard, applauds Womack’s approach, reenforces the need for ongoing study of employer innovations that thwart labor, and calls for wider use of labor’s traditional strike weapon.

Katy Fox-Hodess, a lecturer in work and employment at the University of Sheffield, England, and a former ILWU organizer, supports Womack’s emphasis on the power of employees strategically placed in major industries such as auto manufacturing and port transportation to create disruptive waves beyond their immediate workplace. But Fox-Hodess criticizes Womack’s view that “associational power” is usually of marginal importance. On the contrary, she holds, in certain situations associational power, such as popular, moral, or political support, can be crucial to a union campaign’s success.

Cary Dall, a former ILWU organizer and internal organizing coordinator for a railroad brotherhood and recently an ILWU longshore Local 10 member, also favors employing both strategic and associational power to enhance labor’s fortunes. He emphasizes the often-neglected importance of “reorganizing” union members through internal labor education. Jack Metzgar, an emeritus professor of humanities from Roosevelt University in Chicago with extensive experience in labor education, likewise feels that Womack focuses too narrowly on strategic positions in deemphasizing the value of “associational power,” which he calls “solidarity among workers and with the broader public and the willingness to act in association to change circumstances.”

Joel Ochoa, a retired labor and community organizer originally from Mexico, has worked for the AFL-CIO in California and been an international representative for the International Association of Machinists. He looks at the negative impact on labor of globalization and neoliberalism in recent years and recommends that unions organize inclusively, particularly by recruiting women and minorities in nonstrategic sectors and forming alliances with environmentalists and other sympathetic groups.

Rand Wilson, an organizer for a number of unions and a communications coordinator during the historic 1997 UPS strike, is especially impressed with Womack’s analysis because it puts labor on the offensive by arming it with strategies for how workers can gain power. But he adds that in a campaign, shop floor leaders willing to take action are often just as important as strategically placed workers.

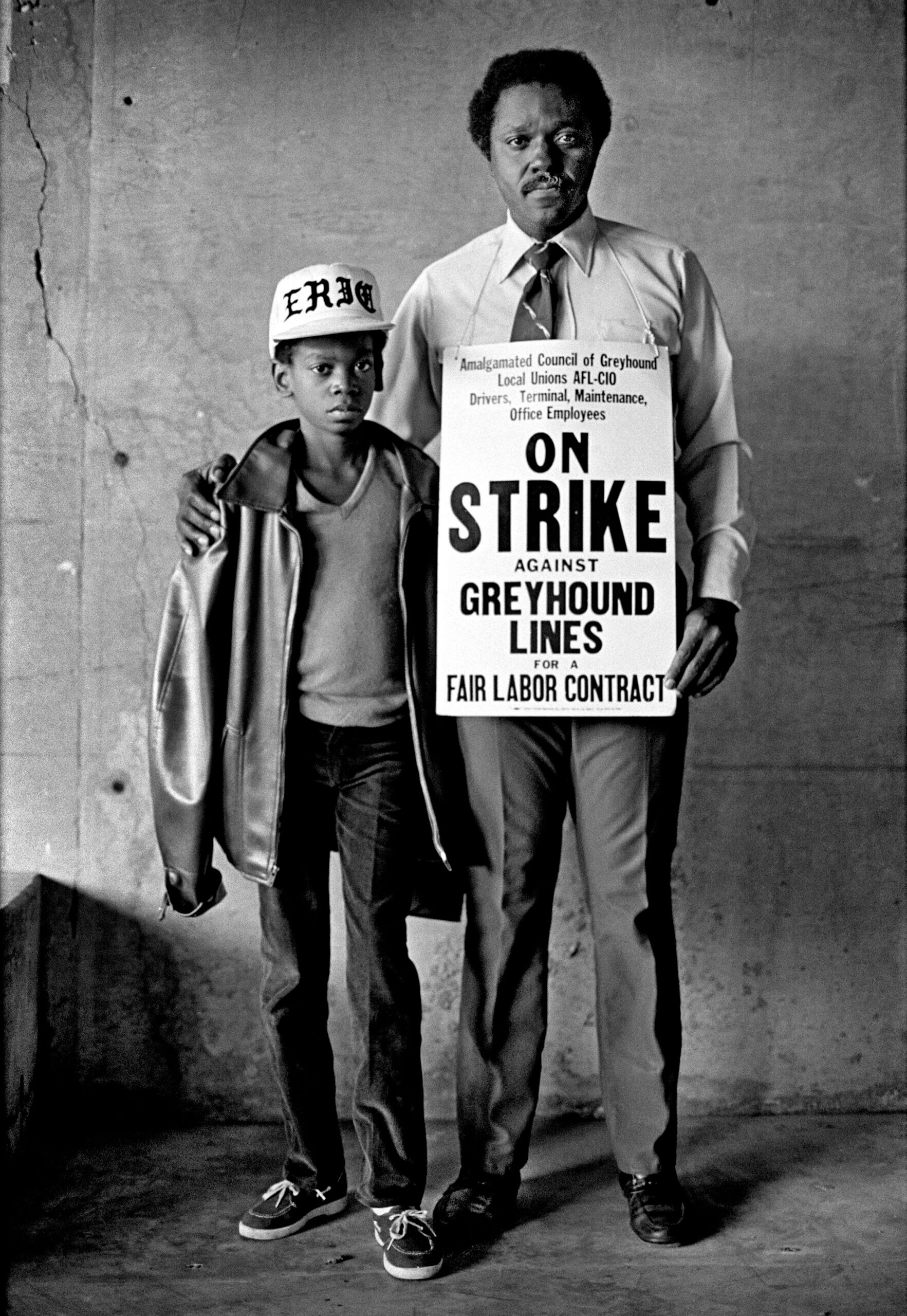

Jane McAlevey, an organizer with 25 years of experience and a senior fellow at the University of California, Berkeley, Labor Center, who died tragically last year, points out that, in thinking about Wolmack’s counsel, differences between the private and public sectors need more study. McAlevey also emphasizes that women, employing both strategic power and public support, have led the most dynamically successful strikes over the past 30 years, namely those in education and health care.

Melissa Shetler, a unionist and a Cornell University labor educator, calls for labor education that welcomes student-worker participation and prepares organizers to adapt to employer countermoves aimed at sidelining worker power, strategic or otherwise.

Finally, Gene Bruskin, a labor activist for 40 years, who has served as a union officer, an organizer, and a campaign director in the North Carolina Justice for Smithfield struggle, describes in vivid detail how, during 2006-2008, he and his fellow unionists groped toward what was essentially Womack’s “choke point” strategy coupled with some associative power to secure a big organizing victory for Smithfield’s long beleaguered hog-processing workers. Bruskin concludes, “Chalk one up for choke points.”

In responding to the ten commenters, Womack stands by his conviction, as outlined in the original Foundry Interviews, that only industrially and technically strategic “power over production, the power to produce or strike production, is the working class’s specific, essential, radical, critical power.” He expands upon his position at length with several nuanced arguments and historical examples.

Clearly, there is much in Labor Power and Strategy that attracts attention. Consider, for example, Womack’s comment that the National Labor Relations Act, or Wagner Act, which created the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) that is supposed to protect labor rights, is divisive because it sanctions the segmentation of the working class into contract enclaves. With the ascendancy of the aggressively anti-labor federal administration in 2025—President Trump has already tried to cripple the NLRB by firing its commissioner and leaving it stranded without a quorum—union access to any help at all from an even more compromised NLRB might be out of the question.

But perhaps more pertinent for this review is that even while living through the inspiring advances of Solidarity Summer 2023, a reader might have occasionally thought, “Womack’s argument is a stretch here; it will be a long time before we achieve anything like that in our center-right country.” Regardless, everyone concerned with the labor movement and sympathetic to the struggles of workers will find the Womack book highly engaging and well worth reading for its many insights and ideas. In the end, with all its proposals and commenters, it provides much food for thought for us all.

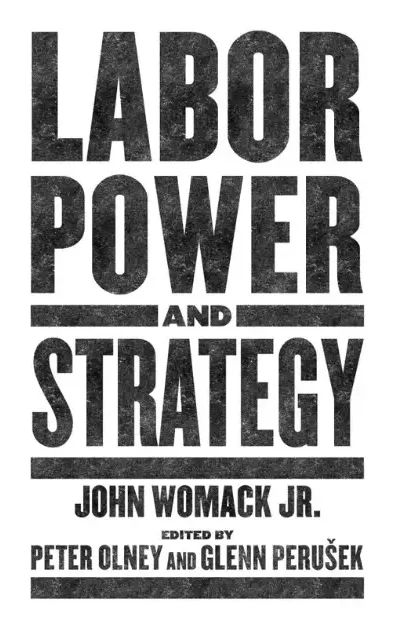

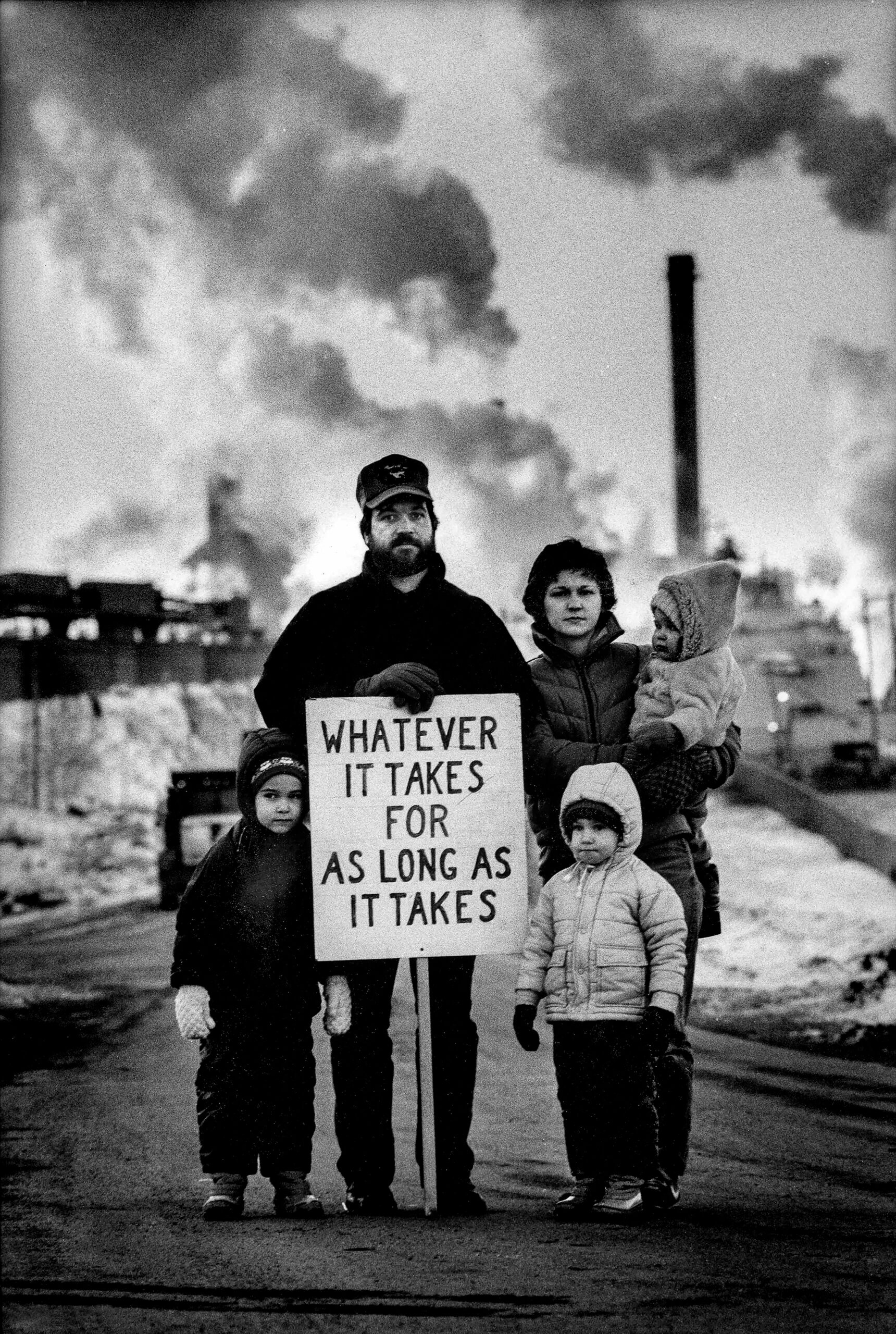

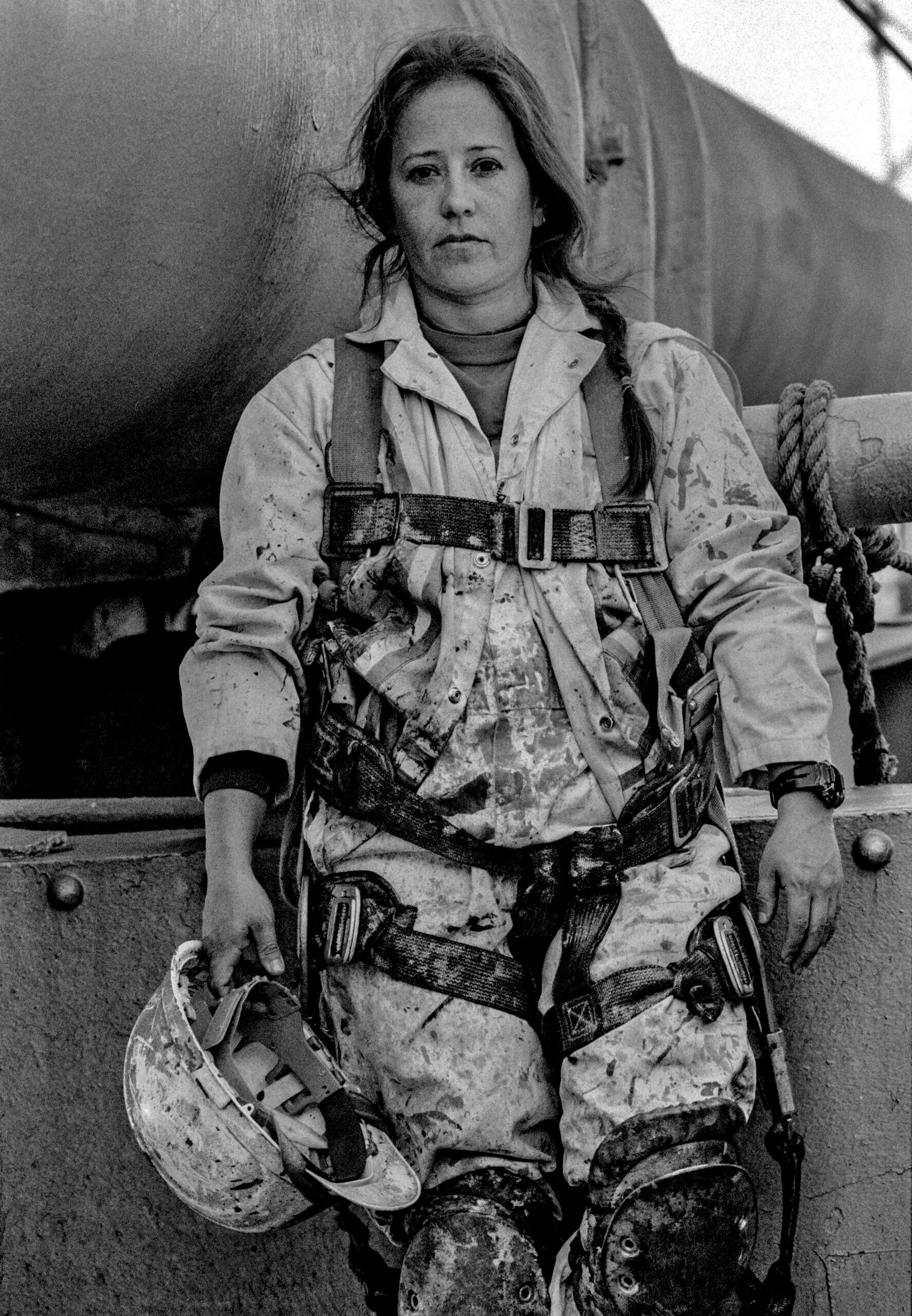

Labor Power and Strategy is a portable (5” x 8”, 190-page) book, so you can carry it anywhere. It is graced by a dozen black-and-white photos of workers and work by the labor and social history photographer Robert Gumpert. There are helpful “Selected Historical Biographies,” an author background section, and a useful index. You can order Labor Power and Strategy through the Powell’s Books Partnership Link on the ILWU Local 5 website, in which case 7.5 percent of your purchase goes to the ILWU Local 5 Strike Fund.