By Vikki Bynum

My forthcoming book, Deep Roots, Broken Branches, contains two chapters about my childhood in Tampa, Florida, from 1952 to 1958. In those chapters, I mention sunny days and long vacations at gorgeous beaches, but nowhere do I discuss hurricanes. Quite simply, although hurricanes threatened Florida throughout these years, none swept through Tampa during my family’s years there. But for sure we endured plenty of storms and rainy days. I well remember the fearful excitement I felt whenever the house went dark from loss of power, especially those nights when Mom playfully converted her face into a shadowy, eerie apparition by holding a candle just below her chin. Even more vividly, I remember one hot summer day when the streets of Tampa flooded after thunderstorms pounded the city for an entire week. Once the rain stopped, the neighborhood belonged to us kids! Dogs chased us as we struggled to pedal our bicycles down the center of empty streets turned into rivulets. When two teenaged boys paddled by our house in a canoe, I laughed in delight.

Today, as I absorb news reports of the deaths and destruction wrought by hurricanes Helene and Milton, it’s hard to imagine a flood being the source of so much fun. So hard that I found myself questioning childhood memories and deciding to research the history of hurricanes and floods in Florida during the years of my youth. Turning to the 1950s Tampa Tribune, I was soon gratified to find an article dated August 6, 1957, that dovetailed perfectly with my memory and the location of the flooded streets of Tampa. After describing “rain-flooded streets, yards, and highways”, the Tribune reported there was “no scientific explanation for the chain of thunderstorms that doused Tampa for the past week.”

As I continued searching, I found the Tribune‘s reporting of hurricanes and tropical storms over the years more interesting than Tampa’s 1957 flood. I was especially struck by one article that questioned whether humankind might one day control, even defuse, hurricanes. In “You can’t Argue with a Hurricane”, published October 2, 1955, author Roger D. Greene likened men’s inability to control women to the deadly hurricane “sisters” of 1955, “shy Alice” and “vicious Janet,” surmising that “mankind” might never succeed in “throwing a halter on these dangerous ladies from the tropics”. Analogizing women and hurricanes is an old trope that didn’t exactly fascinate me. But the heart of Green’s article was a theory that proposed dropping Atom bombs on hurricanes. That grabbed my attention!

Although a fear of hurricanes wasn’t part of my childhood, as an Air Force brat, fears of atom bombs certainly were. Beginning in 1947, the year of my birth and the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, tensions over the possible use of atom or hydrogen bombs permeated my world. In Deep Roots, I recall the unannounced air raid siren tests that regularly pierced the air, warning citizens of a communist invasion. Those sirens, along with bomb shelters, promised to keep us safe. Still, just in case our bodies were burned to death in an explosion, the schools provided kids with dog tags so that we might be identified. This was nuts! As an adult, I learned that atom and hydrogen bomb threats between the “free” and communist world were used to deter an actual “hot” war of mutual annihilation. Maybe so, but in 1961, during the standoff between President John F. Kennedy and Premier Nikita Khrushchev over the Cuban missile crisis, fears of an atomic war shot to new heights.

Remembering my Cold War fears, I was perplexed to learn from the Tribune that some people of the fifties called for an atomic “deterrence” of hurricanes as well as communism: “Why are we hoarding our atomic bombs? Drop an A-bomb into the hurricane and destroy it before it destroys us!” were the purported words of a citizen to the U.S. Weather Bureau. Even before the fifties, as reported in the Miami Herald on August 23, 1945, Miami’s Mayor Herbert Frink urged President Harry Truman to launch a bomb into the next hurricane that threatened Florida’s shores. Truman demurred, but as tensions mounted between the United States and the Soviet Union, the idea gained traction. In 1950, Paul H. Kutschenreuter, a regional director of the U.S. Weather Bureau, warned that bombing a hurricane would be “hazardous to say the least”, but in 1955, North Carolina Senator W. Kerr Scott, a Democrat, called again for its consideration. On August 25 of that year, the Tacoma News Tribune reported that a Texas petroleum geophysicist presented the idea to Democratic Senator Lyndon B. Johnson, who prudently passed the query on Dr. Francis W. Reichelderfer, chief of the U.S. Weather Bureau. “It would take 1000 atomic bomb explosions a minute to match the kinetic energy of a single moderate-size hurricane”, responded Reichelderfer. “The inherent dangers of such an experiment puts it beyond consideration at the present time.” [Italics mine] A bit more emphatically, Theodore Gleiter, head of the bureau’s hurricane warning system, stated that “radioactive fallout from an atomic explosion in a hurricane would kill 10 to 1000 times as many people as the storm itself.” Well, that was the end of that, I thought to myself with relief. The learned men of science had prevailed over the political anti-communist hysteria of the times.

Not so, I soon learned. In a 1961 speech to the National Press Club, bureau chief Reichelderfer announced that scientists, including himself, were “hopeful” that the bombing of a hurricane might occur during the next two or three years. Still, Reichelderfer assured his audience that more studies of “side effects” were needed and that the project was still in the “think stage.” He seems publicly not to have addressed the matter again before his retirement in 1963. Periodically, others did, however. On August 25, 2019, the American news website, Axios, reported that then-President Trump repeatedly questioned senior administration officials about the feasibility of “nuking” hurricanes. Trump pronounced the Axios story “fake news”.

During the late sixties and early seventies, which I describe in Deep Roots as my “earth mother” years, times seemed to be changing. Had I known about earlier calls to bomb hurricanes to smithereens, I would have considered them a relic of 1950s anti-communist rhetoric. But not now. In 2024, I see them as a harbinger of the international campaigns of mutual destruction that dominate the world today.

************

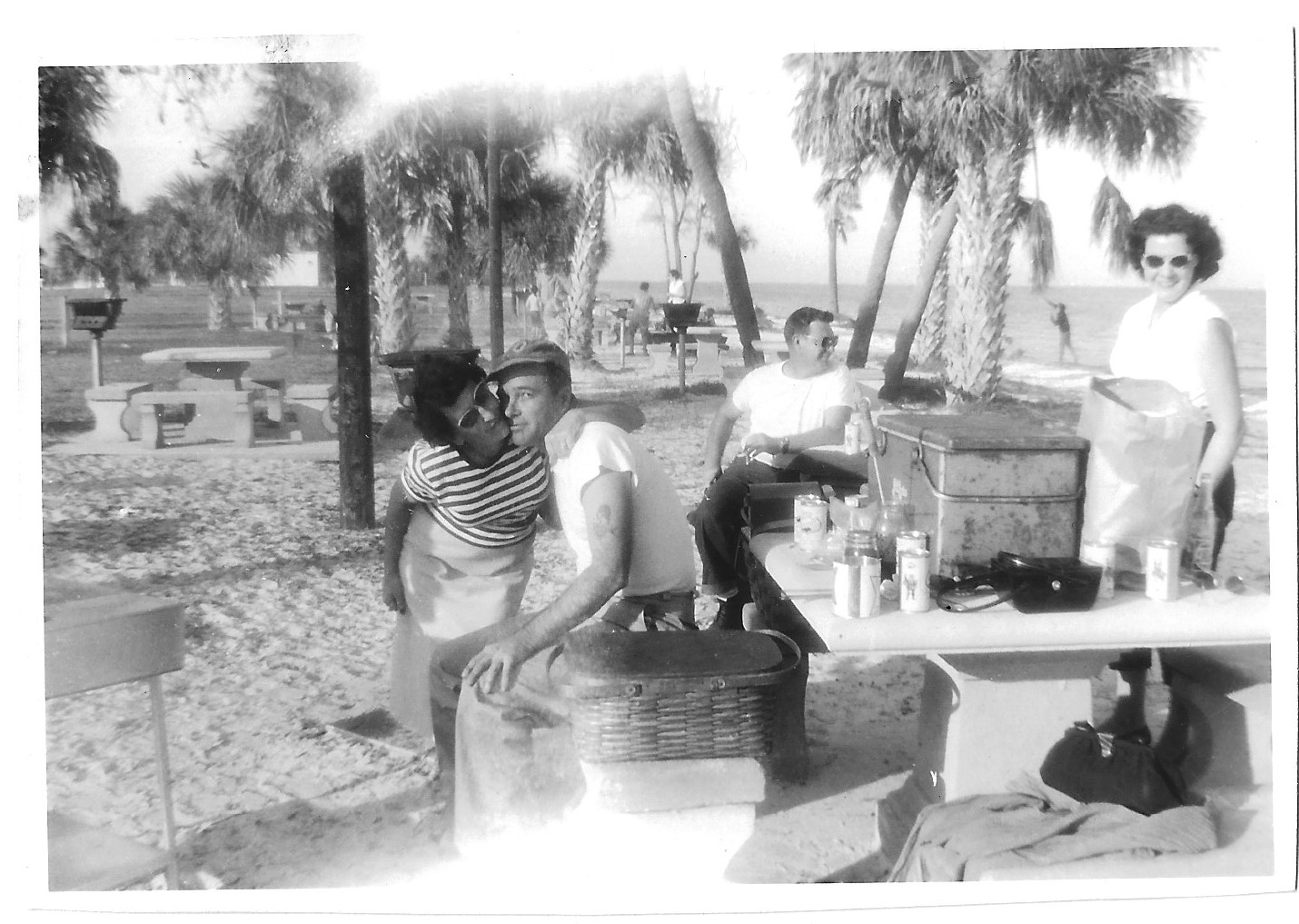

A Florida Beach Party, 1956

NOTE: For more information on Deep Roots, Broken Branches: A History and Memoir, forthcoming February 2025, see University Press of Mississippi