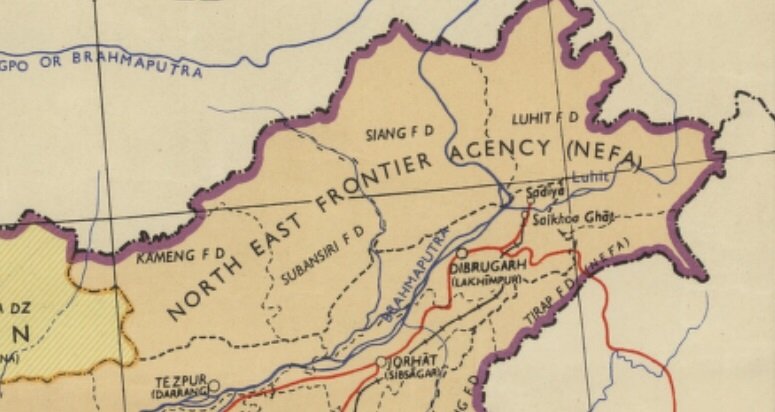

The North-East Frontier Agency in 1954.

The Integration of Northeast India

The history of NEFA, and by extension Arunachal Pradesh, is deeply intertwined with the broader narrative of India’s struggle for independence and its subsequent nation-building efforts. The northeastern territories, with their strategic significance and rich cultural diversity, presented a unique challenge to the nascent Indian state. As the British Empire began its retreat from the Indian subcontinent, the future of these remote regions became a focal point of India’s territorial consolidation efforts.

Following the Partition of India in 1947, the integration of the northeastern territories was pursued with vigor. The region, characterized by its complex ethnic tapestry and relative isolation, had largely remained unadministered during British rule. This lack of formal governance left a vacuum that the Indian government sought to fill, albeit with significant resistance from the indigenous tribes.

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, recognizing the strategic importance of NEFA, emphasized the need for its integration, stating, “We must win the hearts of the frontier people and make them feel a part of India.” However, this approach often clashed with the aspirations of the local tribes, who viewed these efforts as a continuation of colonial domination.

Early Life and Leadership of Tako Mra

Tako Mra was born in 1925 in the rugged hills of NEFA, an area teeming with the vibrant cultures of its various tribes. Growing up in the Sadiya region, Mra was exposed to the rich traditions of the Tani people from an early age. His education, marked by brilliance and an innate sense of leadership, set him apart. From his youth, it was evident that Mra was destined for a path that transcended the ordinary.

The tumultuous backdrop of World War II brought Mra into the fold of the British Indian Army. In 1943, he enlisted and soon found himself leading an infantry in the dense jungles of Yangon (present-day Myanmar). His strategic prowess and courage in the face of adversity earned him high honors from the British. However, the war left a lasting impact on Mra—both physically, as he suffered paralysis in his left arm, and mentally, as it sharpened his resolve for the autonomy of his people.

Reflecting on his wartime experiences, Mra later wrote, “The forests taught me resilience, and the war showed me the cost of freedom. We, too, must fight for our own freedom, not against a foreign empire but against the loss of our identity.”

The post-war period was a transformative time for Tako Mra, marked by his political awakening and growing involvement in the struggle for indigenous autonomy. A pivotal moment in this journey was his encounter with Zapu Phizo, the charismatic Naga leader who championed the cause of a free and autonomous Northeast. The relationship between Phizo and Mra was not merely one of ideological alignment; it was a deep and strategic partnership forged in the crucible of shared struggle and vision.

Phizo, known for his sharp intellect and persuasive oratory, saw in Mra a kindred spirit—a leader with the military acumen and grassroots connection necessary to galvanize resistance. For Mra, Phizo represented a broader framework for the aspirations of the Northeast. Their discussions, often held in secret amidst dense jungles and remote villages, touched on the preservation of tribal cultures, resistance to forced integration, and the dream of a unified hill tribe nation.

Mra’s later writings reveal the profound influence of these exchanges: “Phizo opened my eyes to the possibility of unity among the hills. He believed in a nation not defined by borders but by the spirit of its people.” This partnership was instrumental in shaping Mra’s political strategy, as he began to envision a Northeast where cultural preservation was not just a goal but a right.

Buoyed by his alliance with Phizo, Mra’s growing concern for the cultural and political future of his people led him to engage in correspondence with key Indian leaders and colonial authorities. In 1947, Mra wrote to the Viceroy of India, advocating for the exclusion of the hill tribes from the Indian Union and their establishment as a Crown Colony. He argued that the unique cultural and geographic realities of the region necessitated a different approach, warning that forced integration would only lead to unrest.

In 1948, Mra followed this with a letter to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, cautioning against the incorporation of NEFA into the Indian Union. He warned Nehru that if India persisted in its efforts to incorporate the Abor Hills, his people would resist. Mra’s words were unambiguous: “If India pushes to incorporate the Abor Hills, my men will fight back. We cannot go from being ruled by an elite in Britain to one in New Delhi.”

These letters underscore Mra’s foresight and his deep-seated belief in cultural preservation and political autonomy. His assertion that NEFA was never Indian to begin with highlighted the distinct identity of the region. Scholars today recognize this as an early articulation of what has become a persistent tension in Indian nation-building—the challenge of integrating diverse cultural identities without erasing them.

The 1953 Achingmori Incident

The tensions between the indigenous tribes and the Indian government culminated in the Achingmori incident of 1953, a defining moment in the history of NEFA. The incident occurred when a group of Daphla tribals from the Tagin community, under Mra’s leadership, attacked an Indian government party. The assault resulted in the death of 47 individuals, including Assam Rifles personnel and tribal porters, during an administrative tour in Achingmori, present-day Arunachal Pradesh.

Mra’s leadership in this incident was shaped by his military experience and his unwavering commitment to the autonomy of his people. His war-time tactics were evident in the precision and coordination of the attack, reflecting his deep understanding of guerrilla warfare.

To many in NEFA, the Achingmori incident was not merely an act of rebellion; it was a statement of defiance against the imposition of external authority. It was, in Mra’s words, “a fight to ensure that our children inherit a culture, not a colony.”

Prime Minister Nehru, addressing the Parliament in 1953, acknowledged the complexities of administering such remote regions. He stated, “The fact that that place is not an administered area does not mean that it is outside the territory of the Indian Union. These are virgin forests in between, and the question does not arise of their considering in a constitutional sense what their position is.”

The aftermath of Achingmori saw further internal strife among the tribal communities. The Galong (now Galo) tribe, who were also affected by the massacre, sought retribution. In a tragic turn of events, Mra was betrayed by a Galo girl who poisoned his drink. This act of betrayal, possibly stemming from the complex inter-tribal dynamics and the perceived short-lived victory of Achingmori, led to Mra’s untimely death in 1954 at the age of 29.

His death marked the end of an era, but it also cemented his place in the annals of history as a symbol of resistance and the quest for autonomy.

Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

Despite his premature demise, Tako Mra’s legacy endures as a symbol of resistance and the quest for autonomy. His warnings about cultural assimilation and the loss of identity resonate with contemporary struggles faced by indigenous communities across the globe. The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the ongoing push for greater autonomy under the Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution are contemporary manifestations of the tensions Mra foresaw.

Mra’s vision of a unified, autonomous hill tribe nation remains a poignant aspiration. His life serves as a reminder of the importance of cultural preservation and the right to self-determination in the face of modern state-building efforts. His story, though often relegated to the margins of history, offers valuable insights into the broader narrative of nationhood and the enduring quest for identity.

As historian A.K. Baruah aptly puts it, “Tako Mra was not just a leader of the Tani people but a visionary who understood the fragility of cultural identity in the face of political assimilation.” His life and vision underscore the importance of self-determination and the preservation of cultural identity in the ever-evolving narrative of nationhood.

Find that piece of interest? If so, join us for free by clicking here.

Suggested Reading

-

“Escaping the Land” : Mamang Dai

-

The Assam Rifles Securing the Frontier, 1954–55.

-

The Battle of NEFA–the undeclared war : Bhargava