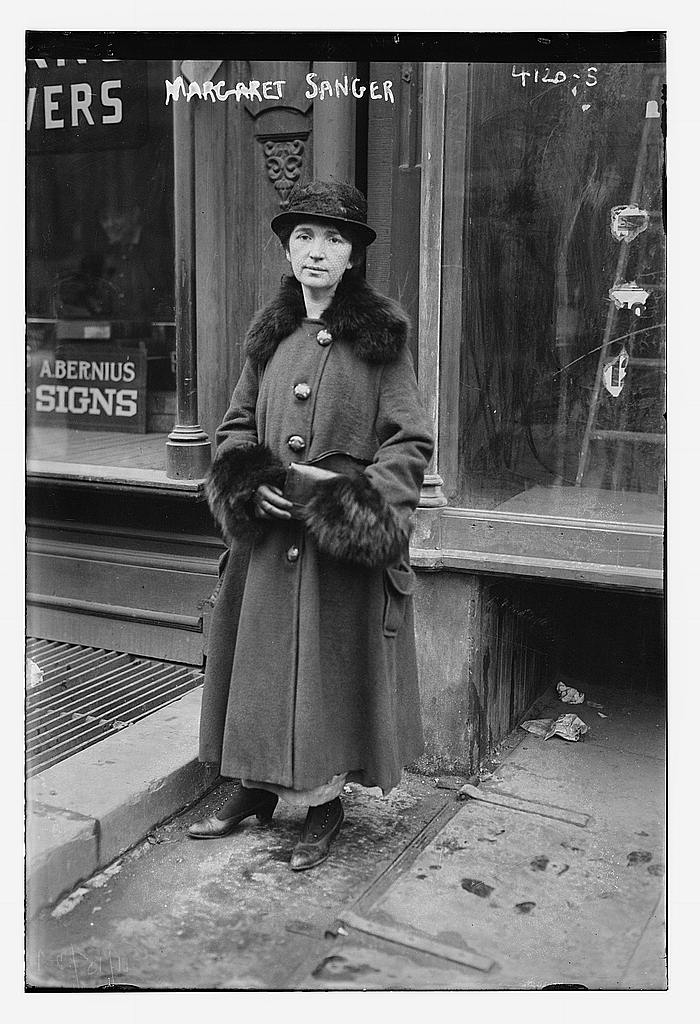

The letters are heartbreaking. Women who had borne three, four, five, or more children in as many years of marriage wrote to Margaret Sanger (1879–1966), begging her to “tell me how to keep from becoming pregnant.” Today, it’s hard to imagine how many American women in the early twentieth century, especially lower-income, less-educated women, were ignorant about birth control. One letter-writer told Sanger, “I, like many women, am interested in Birth Control, …that is exactly the reason I want you to help me.” Another said, “I am constantly living in fear of becoming pregnant again so soon.” Sanger’s mother was pregnant 18 times, delivered 11 live births, and died at age 49. Margaret devoted most of her life to helping other women avoid the same fate.

In a magazine she began publishing in 1914, The Woman Rebel, Sanger wrote:

“Is there any reason why women should not receive clean, harmless, scientific knowledge on how to prevent conception? Everybody is aware that the old, stupid fallacy that such knowledge will cause a girl to enter into prostitution has long been shattered. Seldom does a prostitute become pregnant. Seldom does the girl practicing promiscuity become pregnant. The woman of the upper middle class have all available knowledge and implements to prevent conception. The woman of the lower middle class is struggling for this knowledge.”

Sanger trained as a nurse before marrying and starting a family, but after a fire destroyed her family’s home, Sanger, her husband William, and their three children moved to Brooklyn, NY. There, Margaret began working as a nurse in the slums of New York and Brooklyn, where she saw first-hand the impact of women’s reproductive ignorance – frequent unwanted pregnancies, botched back-alley abortions, damaging self-induced abortion attempts, and premature death. Most of the women Sanger treated were married. They wanted to limit their family to a physically and financially manageable size.

Her experiences convinced Sanger that teaching women about their bodies and the best practices for blocking unwanted pregnancy was more important than strict adherence to misguided legislation. The Comstock Act, passed by Congress in 1873, prevented the distribution of obscene material through the mail. Birth control literature was defined by the law as obscene. Many states passed similar laws that prohibited the dissemination of birth control products and information about birth control.

Sanger opened the first family-planning clinic in the United States in Brooklyn on October 16, 1916. Within days, she was arrested in an undercover sting. While on bail, she continued to distribute birth control information and was arrested again. After authorities pressured her landlord to evict the clinic, Sanger was forced to close it. It had been open less than 30 days.

In a 1917 essay entitled Voluntary Motherhood, Sanger described her determination this way:

“I felt so powerless. I had no influence, no money, few friends. I had only one way of making myself heard. I felt as one would feel if, on passing a house which one saw on fire and knew to contain women and children unaware of their danger, one realized that the only entrance was through a window. Yet there was a law and a penalty for breaking a window. Would any of you hesitate, if by so doing you could save a single life?”

Sanger continued to ignore the laws against distributing information about birth control and how to obtain birth control products. She was arrested several times and once chose a 30-day sentence in a workhouse instead of paying a $5000 fine. Sanger spoke to many groups about birth control and even gave a lecture to the Women’s Auxiliary of a Ku Klux Klan local.

In her talks, she told the story of “Sadie Sachs,” a woman Sanger nursed who had developed a sepsis infection after a botched self-induced abortion. Sanger listened as Sadie’s doctor refused to give her birth control information. “I threw my nursing bag in the corner and announced,” Sanger told her audience, “… that I would never take another case until I had made it possible for working women in America to have the knowledge to control birth.”

Margaret Sanger’s legacy is complicated. Although she was instrumental in educating women about birth control, thus giving them more agency over their own lives, she was also a Eugenics supporter and member of the discredited movement aimed at improving the population by encouraging so-called superior people to have more children while discouraging others. She supported the United States Supreme Court’s decision in Buck v Bell when the court ruled that forced sterilization of mentally disabled women was constitutional. Planned Parenthood, the pro-choice organization that promotes family planning, sees Sanger’s Brooklyn short-lived clinic as the birthplace of their organization. Though the group supports abortion, Sanger did not. Her goal was to end unwanted pregnancies before they happened. On its website, Planned Parenthood “denounces” Sanger’s support of the Eugenics movement while celebrating her role in teaching women where babies come from.

Ray Tyler was the 2014 James Madison Fellow for South Carolina and a 2016 graduate of Ashland University’s Masters Program in American History and Government. Ray is a former Teacher Program Manager for TAH and a frequent contributor to our blog.