Associations are worth the effort

In February 2025, a number of Current editors attended the Christian Writers Conference at Grove City, which centered on the work and ideas of Wendell Berry. Being around people with shared interests gives one a sense of belonging—and belonging was at the heart of the conference, just as it is at the heart of Berry’s work. In Wild Birds, Wendell Berry writes about “The Membership” of the people in his fictional Port William: “The way we are, we are members of each other. All of us. Everything. The difference ain’t in who is a member and who is not, but in who knows it and who don’t.”

Most of us are, theoretically, members of many different associations. We are citizens of a country. We are residents of a county. Most of us have a workplace. We may be alumni of some alma mater. We may belong to a church or a club or a kickball league. We may be descendants of the Daughters of the American Revolution or the best fisherman in the region. These different memberships mean different things to us. They present different responsibilities and play varying roles in our sense of ourselves.

There are also communities to which we belong that barely exist to others. UnHerd recently published a story about “the secret world of hobbyists.” There are all kinds of people whose hobbies form part of their identity and give shape to a real community. Hobbyist magazines persist. There are men and women in England who still build and conduct steam engines (albeit on the small side). The world of hobbyists is like a world under the floorboards or behind a secret door—there are “clubs that no one would ever know were there if they didn’t accidentally come across them.” In these worlds, people pursue their passions, connect with others, and enjoy life beyond the ins-and-outs of daily production and consumption.

Some communities to which we belong are seemingly untethered from space. The eighteenth-century “Republic of Letters” is an example of this. Its members were writers and thinkers who regularly corresponded with each other on all topics and published books and pamphlets. As Humanities magazine explains, “In thousands upon thousands of letters, members tried out new theories, critiqued ideas, relayed the newest gossip, and chronicled the mundane matters of life. The more international your network, the more cosmopolitan you were thought to be.” Though not restricted by physical territory, it was a real entity in many ways—a source of connection, intellectual engagement among equals, and even sometimes a path to refuge from the state. To make the links clearer, Stanford has mapped the Republic of Letters. Wendell Berry fans are something like a paper republic, too.

Being a member of a community is bigger than being a customer. It requires engagement, often dues, and some level of responsibility. Wendell Berry writes about this in his essay “A Native Hill.” Once he settled back in Kentucky on a piece of land, he realized “I had made a significant change in my relation to the place: before, it had been mine by coincidence or accident; now it was mine by choice.” With that choice came familiarity and responsibility. He writes: “In this awakening there has been a great deal of pain. When I lived in other places I looked on their evils with the curious eye of a traveler; I was not responsible for them; it cost me nothing to be a critic, for I had not been there long, and I did not feel that I would stay. But here, now that I am both native and citizen, there is no immunity to what is wrong.” This includes not only the present, but also the past. He and his native hill were no longer separable.

Americans used to be good at voluntary association. Flip through a vintage Sears Roebuck catalog and be amazed at the variety of pins and such that people would purchase to represent their membership in various clubs and organizations. We had a grange movement, workingmen’s associations, and unions. As Putnam pointed out, we had bowling leagues. Some of those things persist, but many are aging and declining. We are surrounded by people who cannot commit to dinner plans and who believe that taxation is theft.

The decline in association and the rise of alienation are linked. Even non-religious people recognize that the decline of church membership is a bad indicator for people belonging to a place and to other people. Everyone talks about how “adult friendship is hard,” while also waxing shamelessly eloquent about how friendships are “for a season.” Those who manage to get outside their own heads and houses experience better lives. Group exercise doesn’t just make you better mentally and physically, it also gives you better social support.

No doubt much of our national political drama is linked to our inability to manage membership. Lack of engagement in the communities close to us has led us to focus too much on the national scene and consider it the only place where meaningful wins are possible. The unwillingness to accept the responsibilities that come with membership are plaguing us. We treat the country and the culture as though we can press a button and get a result we like. We want privileges and products, but we sidestep our obligations. We fail to see the interconnections between ourselves and others, because we are not very good at connecting. We drive the roads as though they belong to us alone, but we balk at the notion that we ought to be taxed to pay for them.

The way of membership is not easy. It comes with payments of all kinds. It requires keeping things going. It requires keeping up with things. A great community needs great community members. There is an episode of the television classic Northern Exposure where Maurice is complaining that the people of the town do not love their local newspaper enough. Someone objects that his paper “is a major snooze” and there isn’t anything to write about in their town. Maurice shoots back with an example of an interesting story and suggests that “a great newspaper needs a great reading public.” Great communities need great members.

For the last fifty years, we have been acting as though the burdens of membership are too much to bear. We do not want meetings or dues or any kind of expectations about attendance or assistance. We do not want responsibility, especially not for the past or for other people. We would rather drift a bit with the current and perhaps stay on the surface of things. We would rather continue to weigh our options.

As hard as membership is, not belonging anywhere is harder. Coral polyps drift through the ocean, but a recognizable piece of coral, much less a coral reef, requires connection. Not knowing where you are, because you know nothing about where you live, is to be unable to orient yourself in the world. Not having people to spend time with—even if you have to help them move—is to be lonely. Not having places to go where you can be recognized and known (and sometimes annoyed), is to be anonymous even away from screens. Life without the literal and metaphorical infrastructure formed by association is unpleasant. Having only your own life to invest in is having very little.

Membership is not easy or free, but it offers much in exchange for the effort. If we become better at membership, we will have better associations—and be more satisfied.

Elizabeth Stice is a Professor of History at Palm Beach Atlantic University. Her essays have appeared at Front Porch Republic, History News Network, and Mere Orthodoxy. She is the editor-in-chief of Orange Blossom Ordinary.

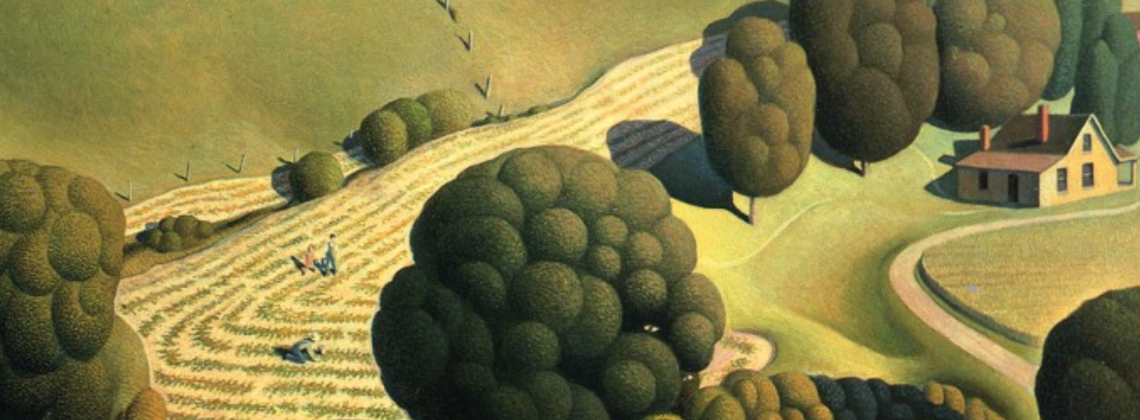

Image: Grant Wood, Young Corn, Cedar Rapids Museum of Art, c. 1931