While most library collections are printed or written on paper, hundreds of historic objects at the American Antiquarian Society — including broadsides, children’s books, and ribbon badges — were printed onto cloth. Often produced as keepsakes, souvenirs, commemorative objects, or teaching tools, cloth printings in the AAS collection include texts and images printed onto silk, cotton, muslin, or linen.

In 2024, AAS staff completed a conservation survey of 150 broadsides and newspapers printed on textiles. Curators and conservators reviewed these objects to assess housing needs and to plan for immediate and future conservation treatments. You can read more about that work in a Past is Present post by Library and Archives Conservator Marissa Maynard. As part of the project, every object was photographed. Those high-resolution images were then archived in GIGI, the Society’s digital asset system, making these textile printings freely available to researchers.

A gallery of more than twenty cloth printings is now available on the AAS website. This “sampler” provides images and brief descriptions of the objects, as well as links to catalog records. Some of the highlights of the resource include an 1806 membership certificate on silk designed and engraved by a woman in Newburyport, Massachusetts; a commemorative menu printed on silk in Saint Louis, Missouri; and a large advertising banner made in New York that promotes the work of poet Walt Whitman.

There are multiple ways to print designs on textiles, including block printing by hand, stenciling, and machine printing. The cloth printings in the AAS collection were all machine printed. The cloth on which they are printed is closely related to the yard goods used for bed linens, clothing, and draperies then being produced at mills across the country. Calico printers were set up in the colonies as early as 1712, running small mills and dye houses near Boston and Philadelphia. After the invention of both the spinning jenny and cylindrical copper plates for printing onto cloth in 1770, the textile industry in Europe and in North America expanded rapidly. By 1836, 120 million yards of printed fabric were being produced in the United States annually.

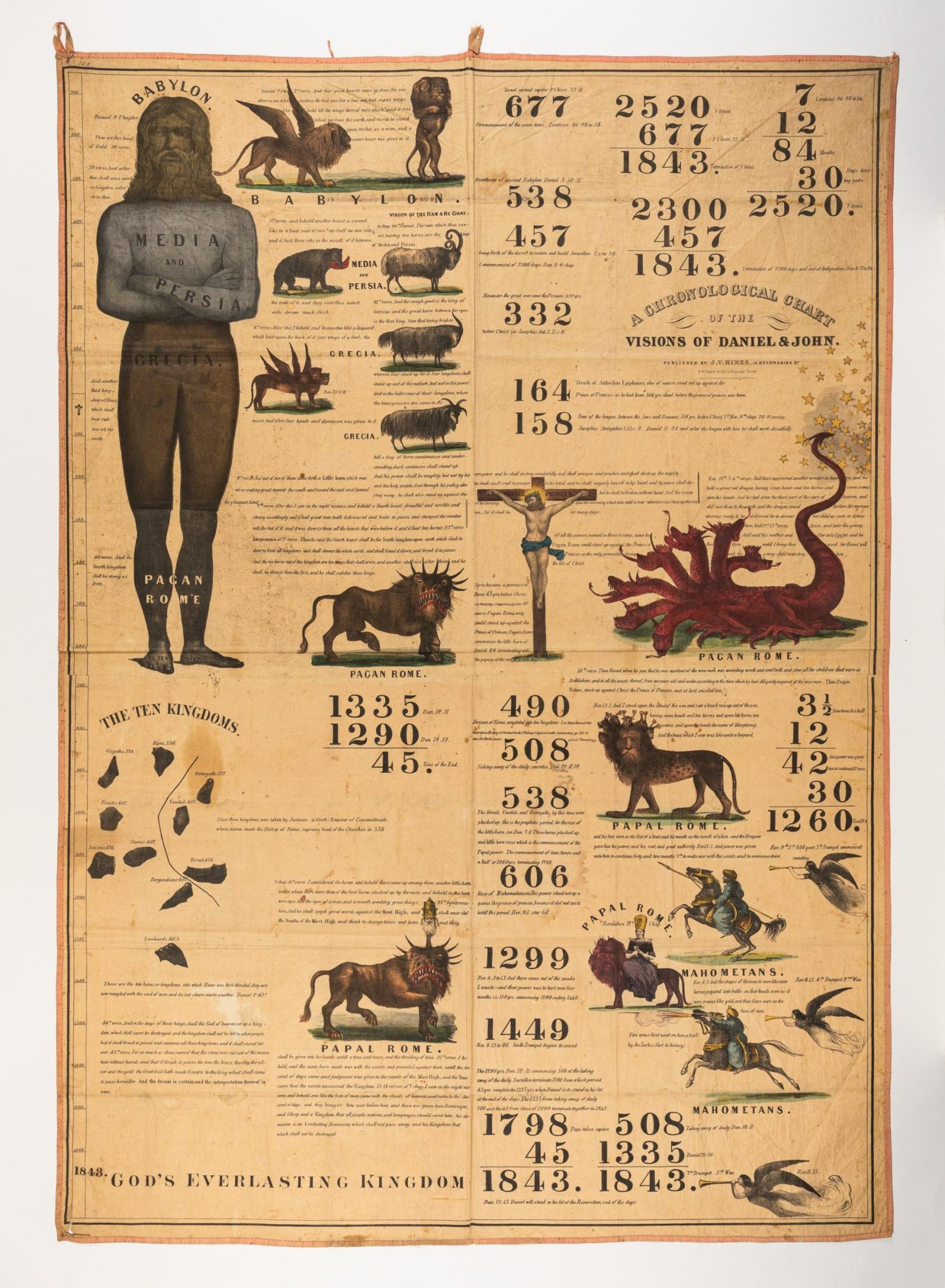

Unlike these mass-produced fabrics, most of the 150 cloth printings at AAS were created in small quantities in the newspaper shops and printing houses of urban areas from Boston to San Francisco. Why did printers choose to make these objects on fabric when paper was the standard and easier to procure? Practicality was often a factor. A religious banner used by Millerites to predict the end of the world was likely printed on textiles to ensure easy transportation from one camp meeting to the next.

“Indestructible” books for children printed on cotton or linen were also practical. Although they frayed when over-manipulated by young readers, they did not tear into pieces the way a paper book would have. Printing on fabric, especially silk, also could enhance the status of an object — silk was recognized as a luxury good in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. A framed membership certificate or memorial piece printed on it would glisten in lamp light, showing off the richness of the object (Insert Decatur memorial)

The examples selected for the new gallery also illustrate how textile printing changed over time as synthetic dyes replaced natural dyes. Because most of the examples at AAS were made locally in job printers’ shops, standard printing inks were used. These tended to fade or bleed more quickly than the dyes used in the textile industry. Some printers used the term “Fast Colors” to indicate that their inks would hold up to wear and tear.

The first synthetic dye in the textile industry (magenta) was introduced in 1864, followed in 1880 by a synthetic blue, which replaced indigo. Because they did not run or bleed and retained their brightness, synthetics quickly made their way into printing inks used by publishers of cloth books for children. One company in Ohio featured a baby chewing on a cloth book as a testament to durability of its products.

Want to learn about how these cloth printings reveal the cultural and technological shifts of their time? Explore the gallery to find out more.

Resources:

The Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife: Textiles in Early New England: Design, Production, Consumption. Boston: Boston University Press, 1999.

Herbert R. Collins, Threads of History, Americana Recorded on Cloth 1774 to the Present. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1979.

Florence H. Pettit, America’s Printed & Painted Fabrics. NY: Hasting House, 1970.