What happens when musicians set their sights on home?

This is an excerpt from Singing from the Heart: The Dady Brothers, Irish Music and Ethnic Endurance in an American City by Christopher Shannon. 338 pp., $15.00

***

By 1979, John and Joe had agreed to quit their jobs at DuPont and pursue music full time. This, in turn, required doing something to show that they were moving beyond the level of a part-time bar band. In the 1970s, there was only one way for them to do this: They had to make an album.

Given today’s digital technology, it is hard to imagine the technical and financial challenges posed by the task of recording an album in the analog era. Rochester had several recording studios capable of producing a professional-quality recording, but the whole undertaking was cost prohibitive for most struggling musicians, especially for those without the steady income of a day job. John and Joe needed someone to back them on a project with no clear guarantee of a return on the investment. They turned to their dad. William, or “Hank,” had always been supportive of his sons in their pursuit of music, but this was different: the desire to produce an album came at the same time that John and Joe were making what, from the perspective of a life-long DuPont employee, could easily have seemed like an irresponsible decision to throw away the security of a steady, good-paying job.

Joe recalls their surprise at their father’s reaction:

We thought he was gonna say: “You’re gonna give up your pension, etc.?” But he says “Ok, go for it.” [I think it was] because he was a musician. And I think, in his mind, if he had his druthers, [if he didn’t] have six kids, he would have become a professional musician himself. So he put up four grand for us for the record. That’s what we needed for the package at Recording Concepts.

Hank made it clear that the money was a loan, not a gift; he expected repayment. John and Joe took the obligation seriously: “So we diligently sold those first thousand records. We sold the records off the stage. We had the money. Put it in the bank [and] wrote him a check.” The sons proudly presented their father with the refund check. He promptly tore it up, saying: “Put it back. Just wanted to give you a little business lesson.” Hank was afraid that John and Joe would end up giving away copies to their friends and fans without making any money.

Perhaps to signal the great leap forward in their careers, John and Joe titled the album, Mind to Move. Choice of material was an issue. Like all musicians, John and Joe got their start playing the songs and tunes of established performers. Keeping bar crowds happy meant playing songs that people recognized. Folk and bluegrass offered one alternative to pop covers, for those genres saw no shame in recording new versions of canonical songs and tunes. Reflecting John and Joe’s experience with these genres, the album included some traditional old-timey tunes, including “Way Downtown,” “Grandfather’s Clock” and a fiddle-tune medley.

Still, John and Joe were not purists. They envisioned the album as a way to set them apart from other music acts; the only way to do this was through original compositions. Aside from a cover of a somewhat obscure Nick Gravenites/Mike Bloomfield song, “Drive Again,” the rest of the tracks were original compositions, most of them written by John. These originals included the title track, “Mind to Move,” as well as “Elaine” and “Hitchhiker’s Lament.” Hinting at John and Joe’s future musical direction, the album also included “Minstrel Man,” an Irish-inflected composition by John. The Irish instrumentation on the album remained limited to Joe’s tin whistle.

The album was very much a family affair. Additional musicians included [John’s wife] Carol Dady and her sister Rose on backing vocals, along with their brother John Culligan on piano. The back of the album cover includes a dedication: “To Hank and Brian”: the Dadys’ father, who had advanced them the money for the recording; and Carol’s brother Brian, who died of cancer at the age of fourteen in 1979, the year the album was recorded.

With a self-produced album, the next professional step would have been to start touring and shopping the album to a record label. The Dady Brothers Band did not take that step. The refusal to tour seemed to undermine the purpose of abandoning their day jobs to go all-in on the music; it even added a note of irony to the title of their album. John and Joe had a mind to stay, for a variety of reasons. John explains:

We never tried to get a contract. I look at it in a few ways. I was married with kids. I married young, I was nineteen. And I’d always hear the horror stories of guys going on the road, coming home and their kids had grown. So I was always afraid of going on the road for more than a couple of weeks. I set that rule many, many years ago. Never wanted to do an extended tour. I don’t know if it was from lack of ambition or fear of success, or the fear that once you sign [a recording contract], you’re under their control and you have to do what they say. If you’re independent you can do whatever the hell you want to do, on your terms. That was always a big thing with us, so I just never felt motivated [to get a recording contract].

Aside from his commitment to Carol and his children, John also made a clear commitment to staying in Rochester and the Tenth Ward: Soon after the release of Mind to Move, he bought his childhood home on Lakeview Park. After five years of living in apartments on and off Dewey Avenue, the family settled down on the street where both John and Carol had grown up.

The house became available due to some major changes in the life of John’s parents. Hank had had serious heart surgery in 1973 and decided to retire from DuPont in 1978. His funding of Mind to Move came at a point when he and Evelyn were planning the next stage of their life: They ended up selling their house in Rochester and moving to Ft. Myers, Florida. All seemed well. Hank was following the American Dream of his generation, John was dreaming a new dream for himself and his family, yet the generations were able to share the continuity of a family home. Hank never got to return for visits to the family homestead: his heart troubles persisted and he died at Ft. Meyers Community Hospital on Monday, December 14, 1981, at the age of sixty. John and Joe had lost their biggest fan and greatest supporter. Grief aside, Hank’s passing must have raised questions about the momentous life choices John and Joe had just made: Why play it safe when you can still lose everything at any moment? Sudden death had denied Hank the comfortable, prosperous retirement men of his generation had come to expect. On the other hand, if one could play it safe with a factory job and still have everything taken away, what worse fate might befall those who took the risk of pursuing a career in music? Only time would answer these questions. As they began the new stage of their life, John and Joe knew only that they had their father’s blessing—and were, in a sense, living out his dream.

By the early 1980s, John and Joe were opening for many of big-time musicians as they passed through Rochester on national tours, while still building up a loyal fan base within Rochester itself. John in particular seemed to have accomplished the extremely rare feat: He was living the life of the Minstrel Man without having to sacrifice the stability of home and family life.

Joe’s situation was a little different. He was not married or in any long-term relationship that would have tied him down to Rochester. Joe’s banjo virtuosity had provided the initial spark for his partnership with his older brother. Musically curious and precocious, he was always picking up and learning new instruments, most importantly, the fiddle. Top-level musicians had high praise for his playing. For a brief moment he considered taking to the road to make it on his own.

I got a call from a guy from Newfoundland in 1982, right after our dad passed away. [He was the leader of] a group from Newfoundland, The Sons of Erin. They were playing at the [Rochester] Irish festival. [The festival] hired John and I to do our gig plus play back behind [The Sons of Erin]. Then he says “Hey guys, you want to go on tour with me? We’re going to freakin’ Los Angeles. I got some gigs out there, I’m gonna pay you this much per week.” John says no, he’s got the young kids. I went. I was freakin’ twenty-one, twenty-two yrs. old. It was kinda like, I got starry eyed. I was in Burbank. [He said]: “Come on down to Paramount.” He had friends down there. I met all these different people. Erin Moran, Henry Winkler [from the hit television show, Happy Days], they’re hanging around. But the other side was he was all for him and you’re a follow up guy. I’m supporting him. One thing I found out is what they say they’re gonna do and what they do are two different things. That’s what I found out then: get a contract. Someone’s gonna hire you on, make sure you get it on paper. But it was a good experience for me.

For The Dady Brothers, the long-term “good” of the experience was to cure Joe of any wanderlust or dissatisfaction he may have been feeling as the junior partner of a brother act.

The door to the road may have closed, but other changes were afoot. The wandering minstrels stayed close to home but still had a mind to move. With life roots firmly planted in Rochester, John and Joe’s pursuit of music roots would take them on a journey across the ocean from America to Ireland.

Christopher Shannon is associate professor of history at Christendom College in Front Royal, Virginia. He is the author of several works on U.S. cultural history and American Catholic history, including American Pilgrimage: A Historical Journey Through Catholic Life in a New World (2022).

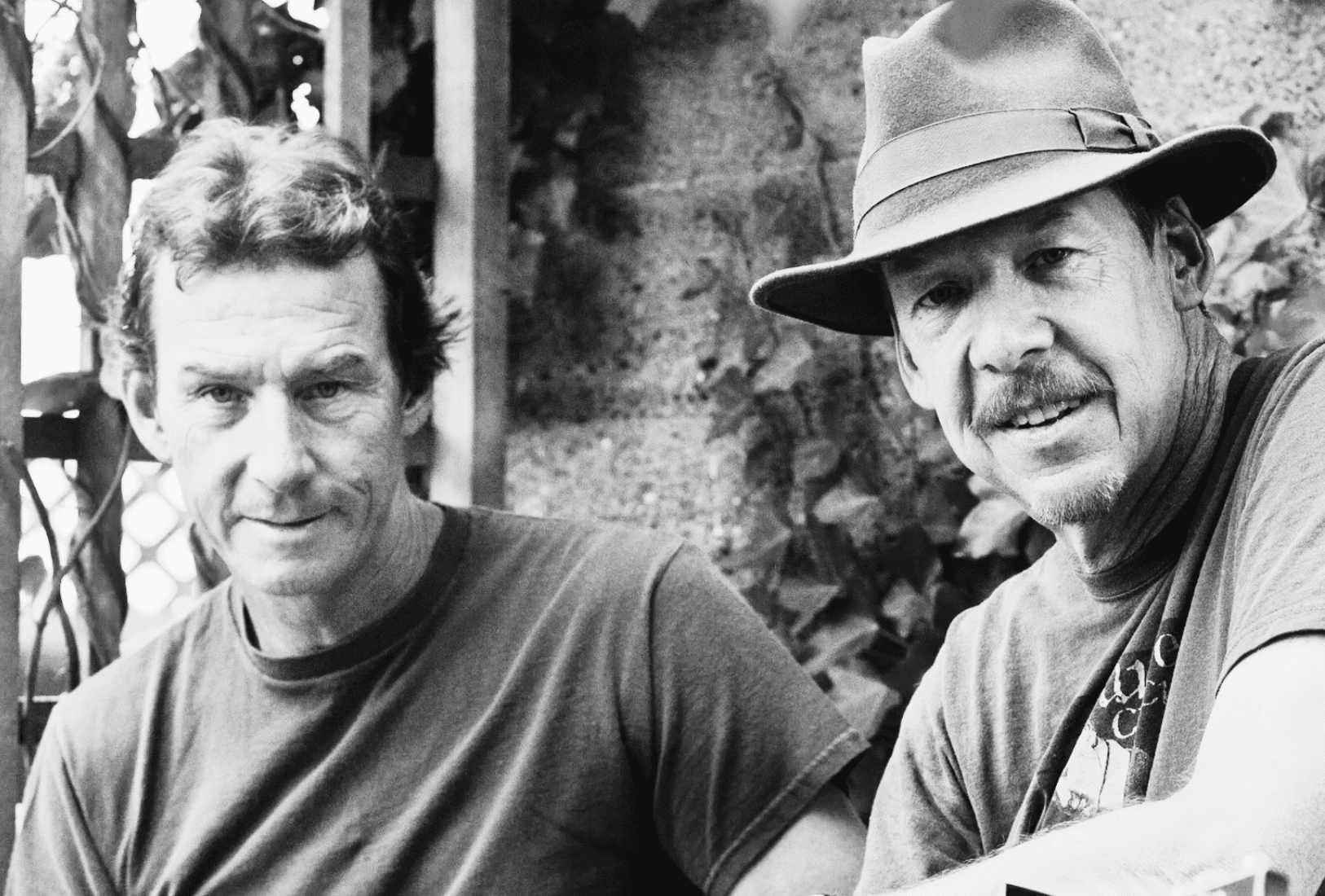

Photo credit: The Dady Brothers