California State University’s Professor of Latin American Studies, Ericka Verba, has published a highly engaging volume entitled, Thanks to Life: A Biography of Violeta Parra. The Chilean folk musician and graphic artist, Violeta Parra (1917–1967), was indeed as the dust jacket claims, “an inspiration to generations of artists and activists across the globe.” She was also very important to me, personally. Let me explain why .[1]

On a warm Saturday morning in 1985, in the period when massive protests against dictatorial rule had just begun to ramp up in Santiago’s peripheral poblaciones, I had a fortunate, unique, and transformative experience. I had taken the bus, guitar in hand, from the población where I lived in La Florida on the southeast edge of the city for the two-hour journey to Pudahuel, on the northwest edge of town. That was where el Mingo lived. He was my partner in a musical duo. Saturday was our rehearsal day.

Our act had become mildly popular on the semi-clandestine protest circuit. Church communities, embattled labor unions, and university students put on shows to raise money for soup kitchens and families of persecuted resistance operatives. We performed for mulled wine, sopaipillas, and bus fare, if we were lucky. Mingo’s crowded home was at the end of the line. Mingo’s family had moved to the capital after the death of his father. Mother and father had been cantores—country musicians—the kind who played and sang for three days at a time for weddings, baptisms, and funerals, before electricity, phonographs, and cassettes. Mingo’s mother didn’t perform anymore. Back in the day, she had played until her fingers bled, while her husband had died of alcoholism—an occupational hazard for los cantores. She had had enough, but her children inherited her the musical talent. Mingo was the youngest, and the most gifted of the all.

That day, on the last leg of my bus ride, I heard music coming from a bike shop on Calle Serrano, the last paved street on the edge of town. It sounded familiar, so I got off before my stop to check it out. There was Mingo, playing and singing with the bike shop owner, whose five wiry sons—under their father’s supervision—repaired the bicycles and cargo tricycles on which working men depended for their livelihoods. Their clever mechanical solutions helped maintain an essential material component of survival.

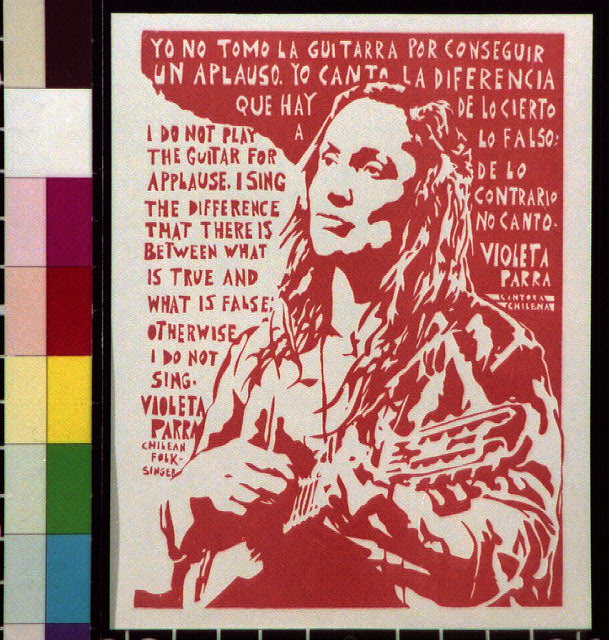

The bike shop’s owner was Don Lautaro Parra, one of the many surviving siblings of the late Violeta Parra. People remembered Violeta as a renowned folklorist, and arguably one of the most influential women that Chile had ever known. Her recordings of Chile’s folk music, as well as her many original compositions in the traditional style, had guided my understanding of how our resistance to the Pinochet dictatorship fit within a much longer struggle for the dignity of working men and women. Since the early days of the republic, they had been oppressed by the predatory inclinations of an unbridled oligarchy. In this context, song was a survival mechanism for the soul.

Don Lautaro was a tall man, expert in bike repair, and honored as working class nobility. Like his famous sister, Don Lautaro played instruments and sang in the authentic, traditional style. He had invited Mingo to join him at the Cementerio General on the anniversary of Violeta’s death, along with friends and family, for an informal a sidewalk singalong—he called it an esquinazo—to honor the godmother of the Chilean soul. He called her, la Chicoca, the little one, a term of endearment, and also, a reference to her short stature in a family of tall brothers. They rehearsed Parabienes al revés, a wedding song about a poor country bride who arrives at the church riding in an oxcart all covered in flowers.[2] Don Lautaro invited me to join, assigning me some very intricate harmonies. He encouraged us to “let our ears grow” until we had mastered the complex possibilities that lurked just beneath the surface of the simple but clever tune.

I missed the homage at the cemetery. I can’t remember why. Communication was not easy. There were no cell phones, and poor people didn’t have ground lines, either, so we might have just missed a signal. But it had been my privilege to sing with a man that Chileans considered royalty, because of his lovely sister, that day.

Violeta Parra was a figure of mythical dimensions for us. Under the dictatorship, people tended to hide or discard her recordings, lest they spark rumors of subversive inclinations. As such, a whispered oral tradition had condensed the memory of Violeta Parra into a few bare essentials. Only a one-dimensional version of the woman who meant so much to us had survived. Ericka Verba’s biography recovers the lost details, the subtle nuances, and the dizzying evolutionary process of the gifted and impassioned artist who created and recreated herself, giving shape, verse, and melody to the common people of Chile.

Verba leaves no stone unturned, using interviews, recordings, and images from Santiago to Paris and Helsinki, to piece together a monumental human endeavor. Violeta’s unique style brought a dying cultural tradition back to life. She thought of herself not as a star, but as the silenced everywoman without whom Chile made no sense. However, not everything Verba has to say is flattering, including a discussion of Parra’s theatrical arrogance, her unbridled temper, and her sense of self-importance. Because of that sincerity, the overall picture stands out as far more reliable than the frequent lionizations that tend to circulate in artistic and political circles. This biography combines rigorous historiographical methods with fine aesthetic and musical sensitivities to formulate an authentic version, with all its symphonic dimensions and awkward dissonances.

Verba frames her lively narrative as the artist’s quest for authenticity. The world of folk music in Chile and abroad had a growing tendency, in the increasingly mass-produced world of music for profit, to lean into an overly polished and often stylized version of itself. The commercial folksingers, like Los Huasos Chicheros, reminisced about an idyllic hacienda experience that affirmed the oligarchic status quo.[3] On two long sojourns in Paris, Violeta even encountered a naive fascination with staged exoticism. She recalls sharing a venue with a duo of upper class women from Buenos Aires, who dressed up as indigenous women from the Argentine pampa, to perform Andean music from a completely different region, for a Parisian audience that couldn’t tell the difference.[4]

As a young woman, Violeta had done her share of barroom singing to survive, With her sister Hilda, they performed whatever the people wanted to hear. But in her early 30s, Violeta experienced an awakening. With the help of her brother, the poet and physicist, Nicanor Parra, she discovered the profound artistic value in the authentic traditions of her own people.[5] She became a collector of the people’s poet-songs, and then a composer, in a style that she knew by instinct from her childhood. Verba points out the paradox of “becoming authentic,” but she shows that the artist herself lived that paradox. Performance, by nature, involves artifice, but Violeta’s brand of artifice found its beauty in truth.

A pivotal paragraph at the end of Chapter 3 captures her struggle for authenticity:

“In her newfound vocation as folklorista, Parra assumed the role of intermediary between the pueblo or folk and her cosmopolitan audience…. A number of factors—some unintentional, others deliberate—contributed to the blurring of lines between folklorista and folk informant: Parra’s claim to authenticity as a birthright… her lack of formal training in music or folkloric studies, her untrained singing voice, unassuming stage presence, and a repertoire of ancient poet-songs that allowed per public to experience her not a s a performer but as the “real thing”; her offstage appearance as everywoman… and finally, encompassing all the other factors, her steadfast identification with the pueblo. Within this context, Parra’s turn to folklore in the early 1950s may be considered the first step in a process of authentication that would span the rest of her life.”[6]

Her careful biographer signals the cultural and technological tipping points that situated Violeta Parra strategically so that she could voice Chile’s broader quest for authenticity. The possibility of recording provided a way to preserve folk traditions from extinction, but they also threatened those traditions with an overwhelming and market-friendly foreign supply. Modernity pushed musical culture—including folk traditions—toward a global standard of success, but that could drown out the front porch style of not for profit musical production. Violeta depended on rooted people, who had lived for generations in the same place, but she herself became a wanderer. Her many years abroad helped her to identify, define, and embrace her local roots.

Violeta Parra found herself in a borderland between the erudite world of artists and intellectuals—her father’s world—and the uneducated country of her mother’s upbringing. Verba points to Violeta’s longing for market success. She thought it was not only her right, but the rightful place of her brand of artistry. In fact, her work, though always critically acclaimed, remained niche. Even in my time, the poor Chileans who appreciated Violeta’s work, and honored her as their champion, could not afford to but it. By then, cassette tapes had made it easy to pirate her recordings—and even easier to hide them from prying authorities.[7]

One recurrent flaw of Verba’s book might not undermine the overall argument of this biography, but it could affect her credibility with Chilean readers. The author tends to make erroneous assumptions about details of local culture. Verba narrates how the Parra children, in a period of extreme poverty, would sometimes steal and drink the chicha they found in people’s sheds. Verba explains that chicha is a fermented drink made from maize. True, Quechua women in the Peruvian altiplano have made it from maize for centuries, and they still do. But that chicha is not particularly sweet or attractive for mischievous children. Moreover, the common chicha found in Chile’s central valley is a cider made from grapes. The “chicha de uva” has been, and still is, the traditional drink for Chilean Independence Day celebrations on every 18th of September, and no Chilean would assume that the mischievous Parra children snuck off with anything other than that.[8]

Additionally, Verba describes how some of Parra’s earliest recordings of the cueca came with the traditional animación, improvised shouts of encouragement that musicians and bystanders tend to provide as part of the usual ritual. The point is that Violeta wanted to demonstrate folk music in its most authentic form, with all of its improvisations and rough edges. But Verba assumes that the encouragement is directed to the singers; It is not. The cueca is dance music: animators encourage dancers to put extra energy into their steps.[9]

Verba’references a special interest that Leonard Berstein showed in Violeta’s performance at an afterparty of the New York Philharmonic’s performance in Santiago. But she doesn’t mention the fact that Bernstein’s wife, Felicia Montealegre, was Chilean. This might partly explain why the world-renowned conductor paid attention to Violeta at all.[10] These details in no way affect the validity of Verba’s research or her arguments, but they merit correction, particularly if an eventual, and probably long-awaited, Spanish version is forthcoming.[11]

More importantly, Verba argues that Violeta Parra pushed the boundaries of gender roles in Chile. She longed to be a star, and she had the right stuff, but the patriarchal system held her back. I suspect that represents a reading of Violeta Parra’s experience from the perspective of first world women, trying to make a name for themselves in a toxic masculine world that thwarts their efforts and achievements. And, that might be a valid reading, if we were talking about the beautiful, protected, and submissive women of the Chilean upper crust, some of whom have broken the mold in courageous ways.

But I would argue that Violeta Parra comes from a tradition of impoverished women who have survived and raised their children over the centuries because of their tenacity, their audacity, and their implacable fighting spirit. Thus, she was not an outlier. Instead, she was a spokesperson for her class. She struggled, not to create a modern space of gender equality, but to preserve a traditional space of feminine prerogative that modernity had begun to eradicate.[12] Perhaps, Violeta is the most prominent, and the most expressive, of this brave and fearless sisterhood, but we need look no further than the Chilean “Families of the Disappeared”—the courageous mothers, wives, daughters, and girlfriends of the men that the Pinochet dictatorship—erased from history, to find the same pattern of fearlessness exemplified in the life and work of Violeta Parra.

In spite of these minor defects in the details, I would recommend Verba’s Thanks to Life not only as a gripping read that puts chronology back into the narrative of a cultural icon on the verge of becoming just a one-dimensional symbol. The humanity of Violeta Parra as a Chilean woman and a world class artist shines through. Moreover, Violeta’s world might serve as the ideal prologue for a syllabus focused on Chile’s impending revolution.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

[1] Erika Verba, Thanks to Life: A biography of Violeta Parra, (Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2025).

[2] See Verba, Gracias, 224. This one of the songs that Violeta depicted visually in a painting that would be included in her one-woman show at the Museum of Decorative Arts in the Louvre, in Paris, in 1963.

[3] Verba, Gracias, 149.

[4] Verba, Gracias, 103.

[5] Verba, Gracias, 68-71.

[6] Verba, Gracias, 91-92. Pueblo, here, means the common people.

[7] Verba frequently notes that Parra was “good at being poor,” but she was not unique in that regard. Her most faithful followers were good at it, too.

[8] Verba, Gracias, 19.

[9] Verba, Gracias, 56.

[10] Verba, Gracias, 161.

[11] This kind of thing is not uncommon. The very prestigious historian, Karin Rosemblatt, in her monograph, Gendered Compromises: political cultures & the state in Chile, 1920-1950 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), situates the action of Nicómedes Guzmán’s novel, La Sangre y la Esperanza, in the neighborhood of the Estación Central, because it mentions a train station. In fact, it is in the neighborhood—in which I lived for a year—of the old streetcar station, which is no longer there.

[12] Chilean anthropologist José Bengoa argues that the sphere of powerful feminine prerogative dates back to precolonial Mapuche communities. See José Bengoa, “El Estado desnudo. Acerca de la formación de lo masculino en Chile,” in Sonia Montecino and María Elena Acuña, eds., Diálogos sobre el género masculino en Chile, (Santiago: Programa Interdisciplinario de Género, Universidad de Chile, 1996), 63-81.