The Briscoe Center’s latest exhibit, History and Fate, is drawn from the personal papers of Richard (Dick) and Doris Kearns Goodwin. The pair met after their time in the Lyndon Johnson administration, in which Dick, a holdover from the Kennedy administration, had been one of Johnson’s principle speechwriters until 1965, and in which Doris was a White House Fellow in 1967 and a domestic policy staffer thereafter.

Despite the exhibit’s name, it is really just about Dick’s life, with the bulk of the displays focused on his time in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

Archivists at the Briscoe acquired the Richard N. Goodwin and Doris Kearns Goodwin Archives in 2022, further cementing the sense that there is no better place to study the LBJ administration than at the University of Texas at Austin. They are distinct from Dick’s government papers in the Kennedy and LBJ libraries.

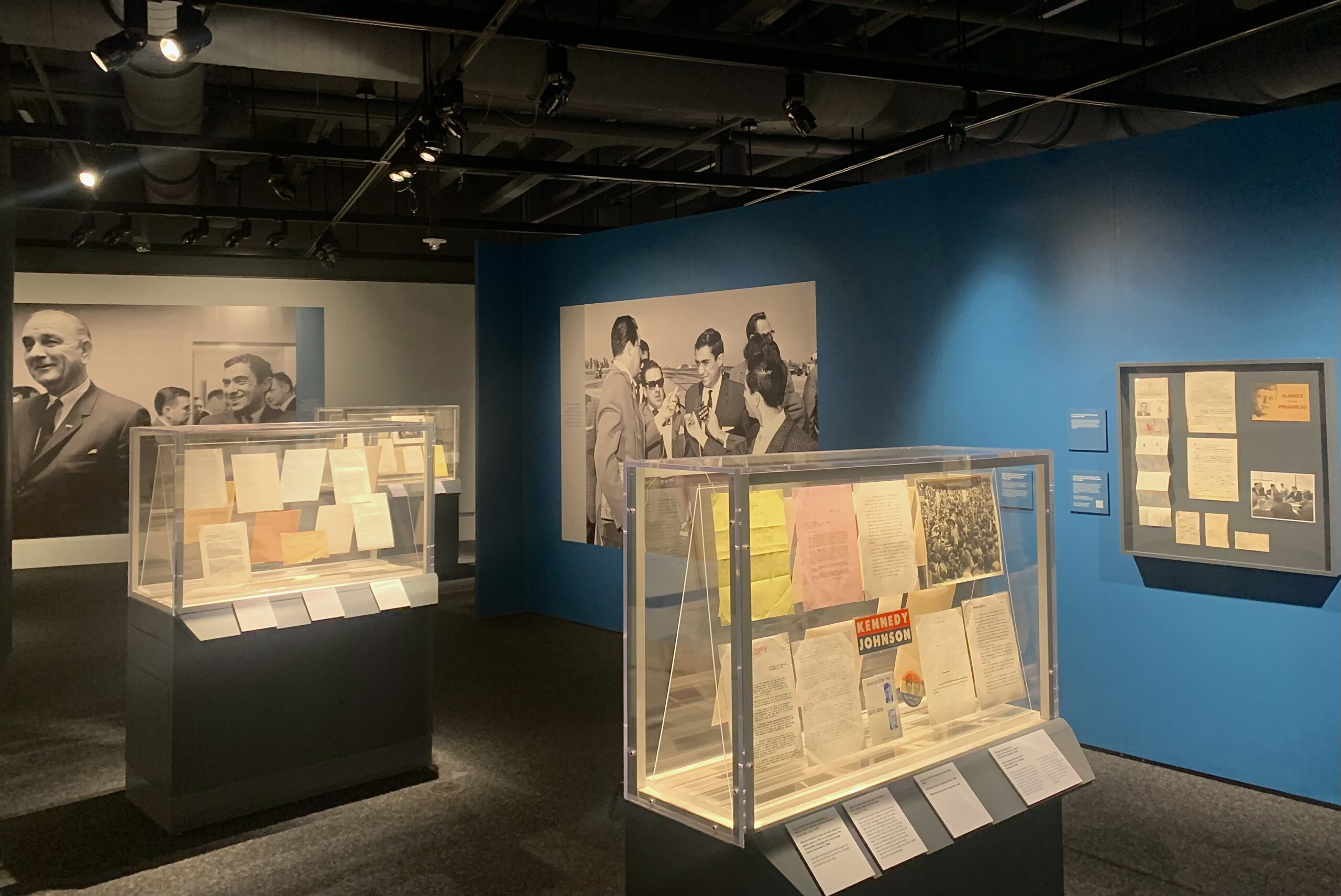

History and Fate is packed with Dick’s correspondence, memoranda of conversation, diary entries, and drafts of speeches. His typewritten diary entries are detailed, giving tremendous insight into how his days unfolded, sometimes down to the half hour. They will surely attract significant scholarly attention, as they offer insights into the inner workings of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations that have previously not been available.

After a brief section on Dick’s college years and early career, things get moving as he joined John F. Kennedy’s congressional staff as a speechwriter in 1959; The exhibit includes the letter offering his services to Kennedy, along with the cover letter of his first Kennedy speech draft. Dick ultimately played an important role in Kennedy’s 1960 presidential campaign, including drafting JFK’s first major civil rights address at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, California. Once Kennedy was in the White House, Dick worked in Latin American affairs, playing a pivotal role in the creation of the Alliance for Progress, a program aimed at developing economic cooperation between the Americas.

Perhaps the most entertaining parts of the exhibit are some of the materials related to Dick’s time working on the Alliance for Progress—particularly his infamous August 1961 meeting with Argentine Communist revolutionary and Cuban Minister of Finance Che Guevara in Punta del Este, Uruguay, where an Alliance for Progress conference was being held. You can see the memorandum of Dick’s conversation with Che, written at President Kennedy’s request, in the exhibit including marginalia, corrections, and such. (For a Brazilian account, see this diplomatic cable. Read Goodwin’s reflections on the meeting over 40 years later in this interview.) In the spirit of revolution, Che gifted Dick a beautifully-crafted cigar box, which is now on display in the exhibit. News of the meeting with Che leaked to the press, causing an uproar and prompting an inquiry by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee’s Latin America subcommittee. Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., a historian and special advisor to the president for Latin American affairs, jokingly sent a Western Union telegram to Dick ahead of the hearing: “Best of luck, old comrade. Give my warm personal regards to Commandante [sic.] Capehart. Che.” The quip about Capehart was a reference to Republican Senator Homer E. Capehart. Dick was transferred to the State Department because of the scandal.

The exhibit’s shift from the John F. Kennedy administration to the Lyndon Baines Johnson administration is, appropriately, quite abrupt. The first item in the LBJ portion of the exhibit is Dick’s diary entry from a few days after JFK was assassinated in Dallas, Texas, in which he recounts his experience of the day of the assassination (reproduced as typed): “It hit me like a shot. I fell to the floor and rocked back and forth saying oh no, oh no, oh no. my body shook with sobs. It cant be true, they cant do this to him. I was paralyzed with emotion.” It reveals the responses of other members of the administration. For example, Schlesinger remarked, per Dick, “what kind of a country is this. Those who preached hate and violence, the far right. This was their doing. Our fault was that we had never taken them seriously. I couldnt listen. I nodded agreement and moved off.”

But the business of government kept moving, despite the death of the Chief Executive, and as early as November 27—just five days after Kennedy’s death—Dick had a memo to LBJ about the Alliance for Progress. On December 6, he started the ball rolling on the creation of the JFK Library.

One item of particular interest is a letter Dick wrote to Jackie Kennedy—with whom he was close—about his decision to remain in the administration after her husband’s death, explaining that he thought “President Kennedy would have advised me to do it,” and that “it gives me an opportunity to do something, in a small way, to advance the things he believed in.” He also intended to leave government shortly after the 1964 election—evidence, in his view, that he was not accepting Johnson’s invitation to stay on as a means of advancing his personal interests.

Dick became Special Assistant to the President on December 10, 1963. In that role, he became one of LBJ’s primary speechwriters, as evidenced by a memo from Bill Moyers—another lead speechwriter—to Dick with a handwritten draft of what came to be known as the “War on Poverty” speech. Dick was forbidden to show the draft to anyone else.

This portion of the exhibit incorporates drafts of some of LBJ’s most important speeches, including State of the Union addresses, the “We Shall Overcome” speech (complete with a QR code to listen to the audio!), LBJ’s speech at Howard University in 1965, and, perhaps most famously, the president’s “Great Society” speech.

Almost as abrupt as the transition from JFK to LBJ, the exhibit rather suddenly introduces Dick’s resignation from the Johnson administration in 1965 with his notes and a letter on his reasons for departing. He felt unappreciated and that he did not have a seat at the table. Additionally, according to a blurb from Doris’ memoir printed on the wall of the exhibit, Dick had also become increasingly critical of the Vietnam War.

Despite his departure, Dick was brought back to draft LBJ’s 1966 State of the Union address, though he ultimately did not retain control over the editing process. So severe was his disillusionment that he never read the final speech and refused to let Doris read it to him.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The portion of the exhibit covering Dick’s work immediately after his time in the White House examines his relationship with Robert F. Kennedy, his brief stint as a part of Eugene McCarthy’s presidential campaign in 1968, and—in what is probably the most striking item in the entire display—his dramatic, unpublished diary account of a police raid on the Conrad Hilton Hotel in Chicago during the turbulent Democratic National Convention in August of 1968.

Coverage of Dick’s post-political career is relatively abbreviated, mostly focusing on his publishing of a memoir and a play, and some personal correspondence. The last panel in the exhibit includes his draft of Al Gore’s concession speech after the 2000 election and a picture of Dick’s meeting with Fidel Castro in 2002, for the fortieth anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Dick died of cancer in 2018 at 86 years old.

History and Fate offers a fascinating glimpse behind the scenes of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, and gives historians a taste of the rich materials of the Goodwin Papers. While the University of Texas at Austin was already the place to study the Johnson Administration—after all, it is home to the LBJ Library and the Briscoe Center also hosts the personal papers of LBJ’s attorney general, Ramsey Clark—the acquisition of the Goodwin Papers at the Briscoe Center further cements its status in this regard.

photo by Jay Godwin 08/21/2023.

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Despite the exciting research opportunities teased by the exhibit, it is not without its frustrations. First, as I wandered around the display, muttering notes into my phone’s voice memo app, I found myself repeatedly remarking that there was a frustrating lack of direction or linearity in the exhibit. While the general order of pre-Kennedy to Kennedy to Johnson to post-Johnson to post-government career was fairly obvious, the more specific timeline of the displays within the exhibit was not. For a chronologically-minded person, the lack of a clearer order was, at times, frustrating. Second, there was surprisingly little mention of Doris in the exhibit, which was confusing given her time in the Johnson administration and her work as Johnson’s preeminent biographer.

That said, History and Fate is a thoughtfully designed and intriguing exhibit that will fascinate both historians and the general public alike. The exhibit is open until July 25, 2025.

Benjamin V. Allison is a Ph.D student in History at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is also a Graduate Fellow at the Clements Center for National Security. His dissertation examines relations between the United States, the Soviet Union, and Arab “rejectionists” from 1977 to 1984. He also studies terrorism and has been published in Perspectives on Terrorism and by the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.