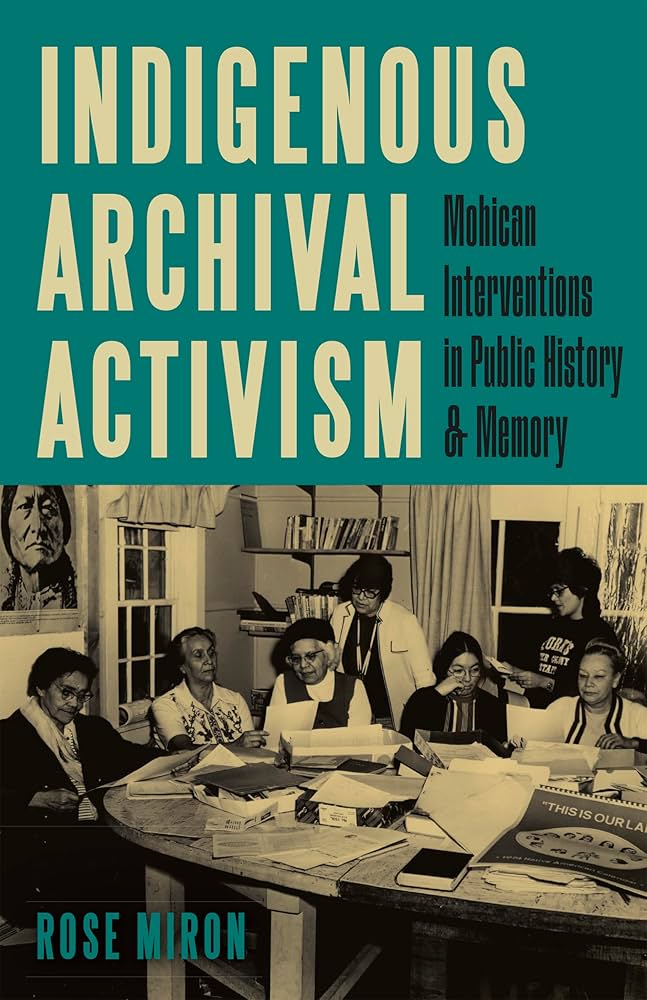

Rose Miron is Vice President of Research and Education at the Newberry Library. This interview is based on her new book, Indigenous Archival Activism: Mohican Interventions in Public History and Memory (University of Minnesota Press, 2024).

JF: What led you to write Indigenous Archival Activism?

RM: I started working on this book in 2010 when I was an undergraduate student. At that time, I was introduced to an oral history video project that the Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican Nation had recently debuted. As I began learning more about the project, I was struck with the tribe’s clear resistance to erasure narratives, especially the famous Last of the Mohicans myth that falsely predicted the tribe’s disappearance. With an oral history project titled “Hear Our Stories” and a final feature in the series titled “We Are Still Here,” I was struck by the way the community was proudly proclaiming not only their survival, but their right to tell their own stories. As I began watching the oral histories at the tribal library and archive, I began talking with the women who led the project — tribal members who served on the Stockbridge-Munsee Historical Commitee. As I talked with them about the Committee’s history and its current initiatives, I realized that the oral history project was only the tip of the iceberg in a much larger effort to recover and reclaim Mohican history. I began working with the tribe to document that history, and we established a reciprocal relationship that led to the publication of the book 14 years later.

JF: In 2 sentences, what is the argument of Indigenous Archival Activism?

RM: Indigenous Archival Activism argues that the creation and strategic use of tribal archives constitute important types of Indigenous political activism and nation-building that fundamentally change how Native history is accessed, represented, taught, and written. The book groups these activities as “Indigenous archival activism” to show how Indigenous nations are working to make their histories and historical materials more accessible to tribal members, to exercise their sovereignty over the retrieval, organization, and description of their records and knowledge, and to contest existing and create new narratives of Native history.

JF: Why do we need to read Indigenous Archival Activism?

RM: This book is ultimately a story about how Indigenous history gets collected, written, and represented in public spaces. By tracing one nation’s engagement with that process, it shows how Native people have been excluded from the telling of their own histories and faced significant barriers to accessing the historical materials that are most relevant to their histories and cultures. At the same time, it shows how much Native communities benefit when they can access these materials and tell their own stories. For tribal nations, I hope the Stockbridge-Munsee story is a model of historical recovery projects, and for those who work in institutions who hold or tell Native histories, including libraries, archives, and universities, I hope it emphasizes that Native nations are the best representatives of their own history. I hope all readers walk away with a sense for how Native history has been misrepresented and erased in public spaces, and what Native nations are doing (and have been doing) to rectify those misrepresentations.

JF: Why and when did you become an American historian?

RM: For a long time, I thought I would be a high school history teacher. But when I started working on this project as an undergraduate, my faculty mentor, Jean O’Brien, encouraged me to consider graduate school, and a career as a historian. I had no idea that path was even an option, but as soon as I started doing research in the archives for this project, I was hooked. As I moved further into the project, I realized that what I love most about being a historian is helping to shift the preconceived notions that people have about American history, particularly the way in which Native people are usually absent from or misrepresented in those histories. I always say that taking a Native history course and doing research in relevant archives turned the way I understood American history upside down, and I wanted others to have that experience too. In working directly with the Mohican Nation and in having the opportunity to engage with some public institutions in graduate school, I came to realize that my favorite way to do that work is through public history, so that is how I ended up at the Newberry working on more public facing projects.

JF: What is your next project?

RM: In the fall of 2024, I helped launch a major public history project called Indigenous Chicago. Alongside a team of community collaborators and other staff members, we spent nearly five years designing a multi-faceted project that tells a new history of the city centering Indigenous people. As we worked on this project, I ended up conducting a lot of the primary source research for Chicago’s early 17th, 18th, and 19th century histories, and I was astonished by how different my findings (and those of our larger project team) were from how this early history is typically represented. I especially noticed that the stories about Chicago’s so-called “founding” were very skewed toward European and American historical actors. I have started working with Eric Hemenway, who is the Director of Repatriation of Archives for the Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa, and who also served on the Advisory Council for the Indigenous Chicago project, on a new book project that would re-tell the history of early Chicago. We hope to co-author the book and have just started talking with relevant Tribal Historic Preservation Officers (most of whom already worked on the Indigenous Chicago project as well) about their priorities for the project, and will be starting to dig into the research soon.

JF: Thanks, Rose!