Happy 100th!

2025 marks the centenary of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. It is one of a few contenders, and perhaps the frontrunner, for the title of “the great American novel.” It was something everyone was trying to write in the 1920s and many suspected that Fitzgerald had done it. He believed he had. It was certainly a fear of Hemingway’s that Fitzgerald had. The centenary of the book’s publication is an invitation to consider a number of things.

First, The Great Gatsby brings to mind the nature of greatness. Despite the admiration of many other writers, Fitzgerald died not very well off in 1940. The Great Gatsby was not widely regarded as a masterpiece and Fitzgerald did not make much money from it. Though it was a book written in the aftermath of World War I, it was World War II that helped make the book. The Great Gatsby was one of the books distributed by the Council on Books in Wartime. It continued to gain traction after that, later becoming required reading for generations of high school students. Today we know it as one of the most important and best novels in modern American literature. Even people who have never read it have some vague sense of its story and may well have seen one of the film adaptations.

What does greatness look like? If the case of The Great Gatsby is any indicator, it may not be immediately apparent. It may be something of a slow burn. It may be a later realization. It may not be recognized in time for the author to enjoy it.

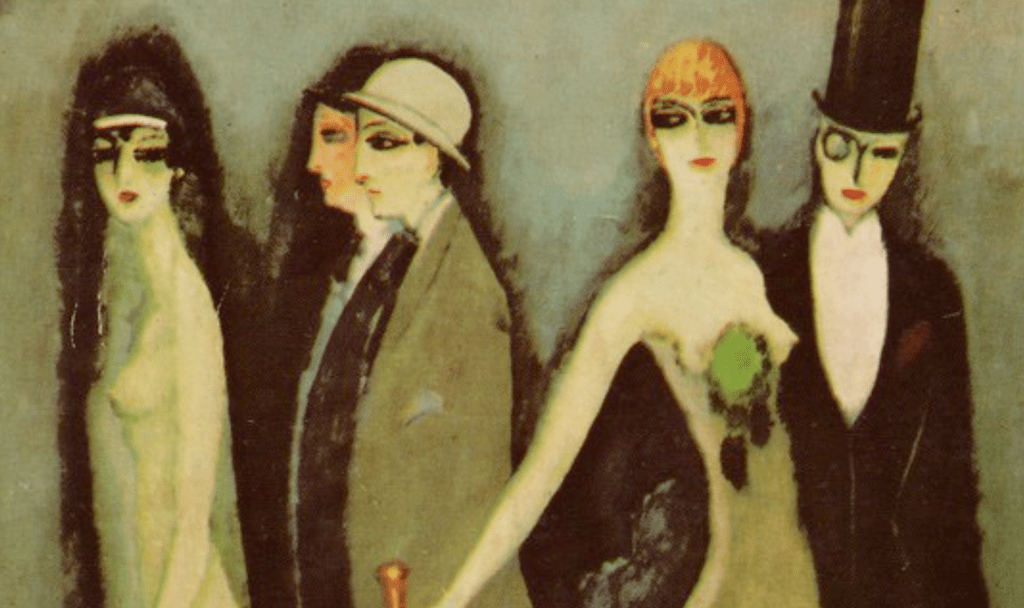

It is also possible that being “great” has made it harder for us, coming along later, to see The Great Gatsby as it is. Its fame may have obscured some of its true greatness. That’s the argument Sarah Churchwell recently made in “How We Misread The Great Gatsby” in The New Statesman. She points out that the yellow cabs and the flappers and the 1920s slang we associate with it and have put into the movies are essentially absent in the book. The style is not that of the flappers, the prose is special but not slangy and dated, and the cabs range from yellow to violet. We have taken a great book and wrapped it in cliché, turned it into a nostalgia piece about the 1920s rather than embracing it for what it is. It brings to mind the last sentence of the first chapter of the book: “When I looked once more for Gatsby he had vanished, and I was alone again in the unquiet darkness.”

Being “great” has also made The Great Gatsby more challenging for people to get excited about. There is nothing like being assigned a great book in high school to spoil the thrill. This is why The Catcher in the Rye is no longer seen as subversive. If you put something on a syllabus, you just may kill the spark. Every good high school student knows that The Great Gatsby is about “the American dream” and features a famously “unreliable narrator.” Do they know that its prose is so good that Hunter S. Thompson allegedly typed out the whole book himself to internalize its rhythms? Doubtful.

Yet for all the ways we misapprehend it, The Great Gatsby has staying power. One hundred years after initial publication it still feels fresh in many ways. It continues to represent the “American dream.” And we continue to chase that dream. We continue to pursue wealth while shaking our heads at the carelessness of the wealthy. We watch The White Lotus and judge the characters while we also wonder what it would be like to stay at that type of resort and have that much money. We like fast cars and parties and wealth and getting what we want, and we are not surprised or dismayed when the people who have it all get what’s coming to them.

The Great Gatsby is also a good example of the challenges that face a cautionary tale. When it comes to Gatsby’s funeral, “Nobody came.” And yet the book is considered a sound basis for a party theme. We do not read it and think about staying in the Midwest and staying out of trouble. We read it and think about an excuse to dance on some tables or use a cigarette holder. The same is probably true of all kinds of American “cautionary tales.” Whether or not the end justifies the means, we want our fun now, and we won’t let the end bother us in the meantime. People watch Fight Club and think it may be a good gameplan. People watch The Wolf of Wall Street and don’t think about getting ruined—they think about getting rich. Like Gatsby, we believe “in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms further . . . And one fine morning—”

In 2025, The Great Gatsby feels a bit on the nose. Some people wonder if we are dancing on the precipice of disaster. Do men like the man who fixed the World Series in 1919 circulate among us? Are we under the surveillance of advertising like the eyes of Dr. T. J. Eckleburg? Do we try to overlook the ash heaps produced by our economy and drive too fast around corners? We seem to have all of that without the pleasure of the “yellow cocktail music.” Is it an argument for the circularity of history? Or support for a static view of our country’s culture?

One possibility to consider is the way The Great Gatsby is like Fitzgerald’s story “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button”: It may have been born in 1925, but it has, perhaps, in some ways, been aging in reverse. Initially it was understood and embraced by relatively few. It became more widely appreciated over time. And the closer we get to our present, the fresher it appears to be, despite its associations with nostalgia. There were more movie adaptations of it in the second fifty years of its life than the first fifty. We can imagine it all happening now because it says something we may have suspected, and now know to be true about our nature and our national culture. The further we get from its birth, the better we see that it is a beautiful book.

Elizabeth Stice is a Professor of History at Palm Beach Atlantic University. Her essays have appeared at Front Porch Republic, History News Network, and Mere Orthodoxy. She is the editor-in-chief of Orange Blossom Ordinary.

Kees van Dongen, Comedia Montparnasse Blues, c. 1925