Labor historians in the United States and Canada often rely on familiar sources, union and company records, newspapers and oral interviews, to name a few. The Moving Past: A Collection of Archival Film is an invitation to consider another source – film.

Canada was the first jurisdiction in the world to have a government-sponsored motion picture bureau. The Ontario Motion Picture Bureau (OMPB) was created in 1917 with a mandate to make films as “educational work for farmers, school children, factory workers and other classes,” and to “give instruction in all branches of agriculture, etc., fruit growing.” The OMPB was also directed to “advertise the resources of the province and to encourage the building of highways and other public works, and other subjects if made more useful with motion pictures.”[1] The following year the Canadian Government Motion Picture (initially under the name ‘Exhibits and Publicity Bureau”) was created to “to advertise abroad Canada’s scenic attractions, agricultural resources and industrial development.”[2] With these mandates it is not surprising that a large number of films featured workplaces in various industries. These films were immensely popular in Canada and there is considerable evidence that they were widely viewed by Americans as well. Though each bureau operated for less than twenty years, a remarkable moving picture collection has been left for historians. Yet it has been underutilized and largely ignored.

There are good reasons for this. Very little of the collection has been digitized. Those interested in screening the films must order them in advance from Library and Archives Canada in Ottawa. Many of the film catalogue descriptions are too brief, vague or occasionally inaccurate. Drawing conclusions about specific films can be difficult. Films must then be screened on poor quality VHS tapes which are brittle and occasionally break.

But the challenges do not end there. If a digital copy of the film is wanted, it is sent to a private lab, which does excellent work. But this is paid by the researcher. Costs vary between $90 to $150, per film, depending on its length of the film and the desired resolution. This is a process for historians who have lots of patience, budget and time.

Yet, this film collection is worthy of our attention, and labor historians, especially, can learn from them. The Moving Past is a new website that features 15 of what is at least a 1,000-film collection. These productions were very popular in Canada in the 1920s as movie going exploded. In fact, one of the reasons these two bureaus were churning out productions was to provide a more “British” product that was educational and appropriate for young viewers and families. There were concerns about movies coming from the U.S. More than two decades before the Hays Code was implemented in the U.S., there was an Ontario Board of Censors that ensured that films produced and screened in Ontario met a certain standard. This three-person tribunal judged the morality of every film shown in that Province. Canadian productions met with the approval of women’s organizations in the United States, and many groups sought them for U.S. screenings. In 1931, only 17 percent of American made films being screened in Ontario were found to be “suitable for children”. [3]

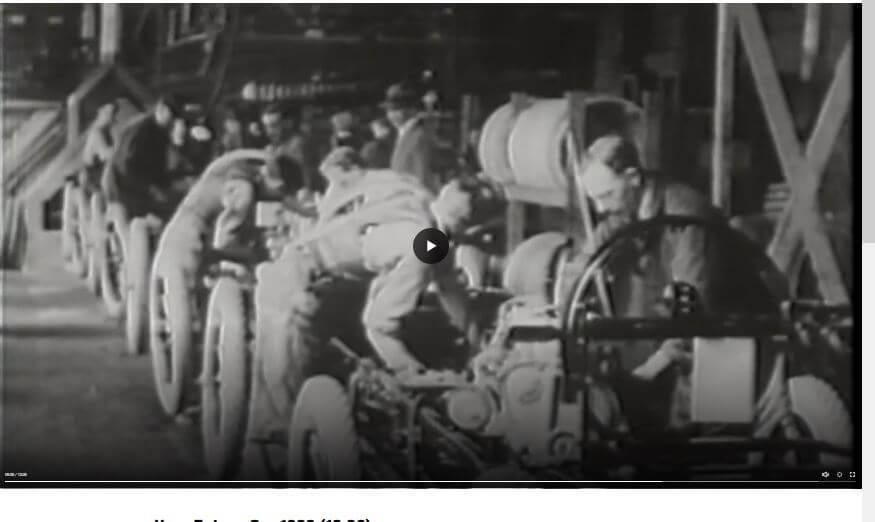

Ontario authorities also believed that while films could be a source of entertainment, their true value was educational. The result was that a sizable proportion of the films are industrial documentaries which depict work and its organization. For example, “Your Future Car” (1922), features the building of a car at Durant Motors in Leaside, then a suburb of Toronto. Technology and the organization of production varied significantly between plants and manufacturers in the auto industry, when the sector was still relatively young. This narrative is sufficiently detailed to document hazards and capture how the organization of work was based on gender and age. For example, we see that the upholstery department is comprised entirely of women. These scenes suggest that Ford’s famous assembly methods were not fully adopted across all manufacturers across all plants. Both Taylorism and craft methods coexist in the same factory. Just a few years after this film was made, Left led unions sought to organize factories in this industry.

Another film, called “The Drive” (1925) is a tale of independence, risk and skill among loggers as they travel down a Northern Ontario river. Felled timber is taken down the Mattagami, a Northern Ontario river. The men who guide the logs on “the drive” are “famous for their dexterity,” as poling and burling are demonstrated. In an amusing sequence, the men are described as “proverbial for their appetite”: one has allegedly eaten a ten-pound bologna, while another consumed 45 eggs, shells and all. The product eventually finds its way to a lumberyard in Toronto to be sold. Ontario’s “treasureland” of forest, mines, and streams helps make Canada prosperous, the film concludes.

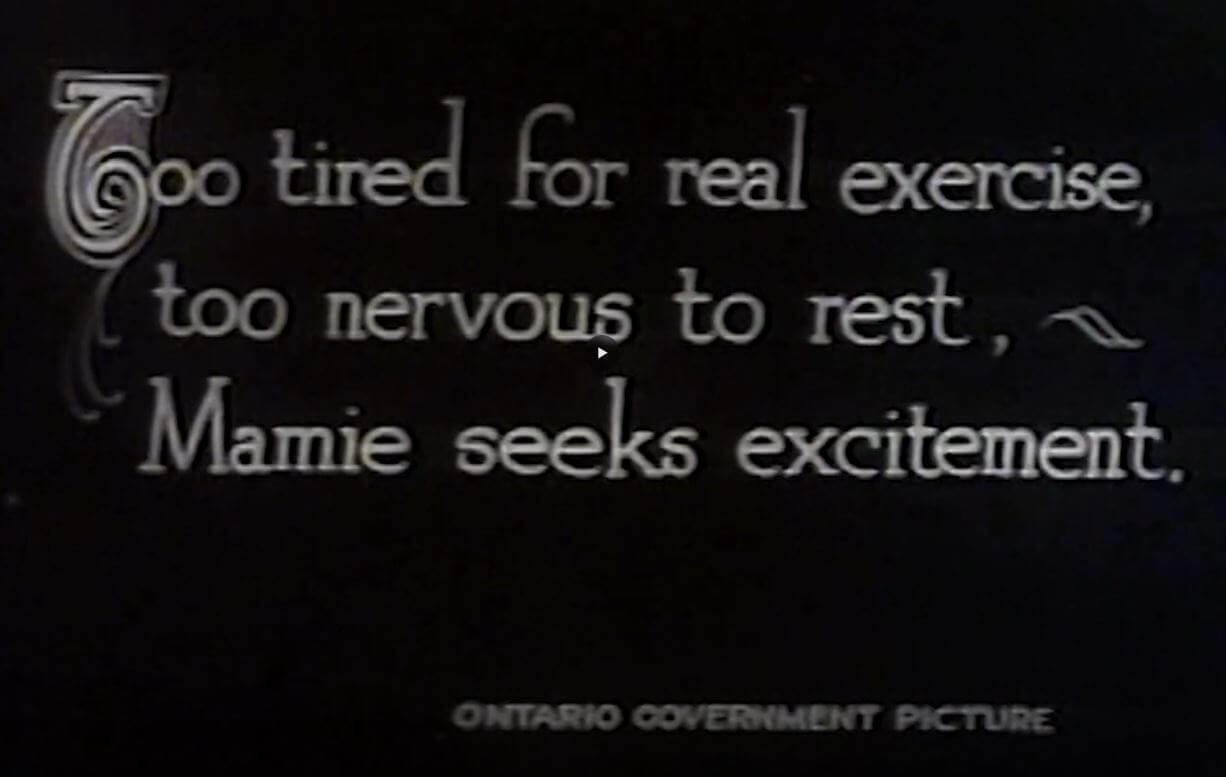

Many films follow this structure, describing the work and its organization. Others are didactic narratives. One called “Her Own Fault” (1922) is especially useful for understanding perceptions of women working in industry. [4] The story depicts living arrangements and work habits as a morality play. The film stars a “good” factory girl and “bad” factory girl, both employed making heels for shoes at the Gutta Percha Rubber Factory in Parkdale, Toronto. The girl who is promoted to “forelady” is also rewarded with a budding relationship with her male supervisor. The “bad” girl “does less each day” and contracts tuberculosis. The film reflects the growing concern that young, unmarried women working in cities would be tempted by the vices that urban life offered. It also suggested the kinds of behavior that would be rewarded if a ‘factory girl’ wanted to achieve success.

In a similar vein, “Someone at Home” (1925) is about workplace safety. It seeks to explain that the real root of industrial accidents, “worker carelessness”, a message that still echoes today. In the film, an electrical lineman named Jim is planning to marry on this day but “won’t take safety seriously.” He’s a bachelor who lives in a boarding house and is late for work. The more fastidious and conscientious worker is married, has two children, and is very safety conscious – a comment on class and respectability and the taming effect of marriage. When an automobile knocks out an electrical pole, power is cut to the hospital, imperiling the life of a little girl. Jim is dispatched to restore the power and is seriously injured. Not taking safety seriously almost costs Jim his fiancée. The film ends with a one-word message: “Think!” It suggests that fatalities and accidents occur because workers are inattentive when it comes to safety.

Finally, there are films that sought to attract American tourists to Canada and Ontario specifically. “When Summer Comes” (1922) was to promote the province to tourists and “sportsmen” by featuring its abundant lakes, forests, and fish. Americans were an important audience in this effort. “Native lore” is used to explain the beauty of the Thousand Islands region. The ease of travel to this wilderness is communicated to wealthy travelers in Canada and the United States through onscreen maps. Georgian Bay offers welcoming hotels and lodges. The accommodation is comfortable, and the food is delicious. Indigenous guides, using their “instincts,” help guests catch fish. This racist trope, along with a disturbing image of a Black woman, illustrates attitudes of this era through a government-sponsored film.

The Ontario Motion Picture Bureau did not rely solely on commercial theaters to build a viewership. A sophisticated distribution and borrowing infrastructure that engaged schools, clubs, churches and community halls made access to the bureau’s film relatively easy. After 1925, the Canadian National Exhibit, a massive event that had been attracting hundreds of thousands in the late summer, furnished the Ontario bureau with its own pavilion after 1925 to show its productions exclusively. [5]

In the case of these Canadian bureau, many titles were shown to conference and exhibit audiences in the U.S. These films also played a role in attracting tourists to Canada’s wilderness, noting both the luxury of the resorts and their proximity to major American cities. For example, in 1926, the film bureau partnered with the Ontario Tourist Board and showed films at the National Automobile Show in New York City. The films were designed to attract American tourists to Ontario, with a reported 200,000 attending the Ontario film screenings.[6]

The Moving Past website launched less than six months ago and currently features 15 short films made between 1918 and 1929. These films offer rich insights into factory and agricultural work, gender relations, and how technological change was presented. While these were state-sponsored films, the perspective is decidedly that of management. Workplaces are wonderful places and workers are satisfied to do their jobs in the manner prescribed. Taylorism and scientific management operated in Canada, just as it did in the United States, which is why these films are useful to American labor historians as well.

Conclusion

The Moving Past is a history project that is designed for academic historians and educators. But it also has value in labor and broader political education that is conducted by unions. Discussions about what is happening to workplaces today need a starting point.

While these films are heavily varnished stories of workplaces and daily life, they are useful in understanding the period. This is what government wanted us to see and ultimately think about. The films fit into the nascent creation of mass communications products. Worker struggles and resistance to how the workplace was changing are absent from the screen.

To appeal to non-specialists and younger undergraduates, period music was added as a soundtrack to what were silent films. As the pacing of century-old films is very slow for contemporary audiences, some very minor editing of long pans and closeups was also undertaken.

As noted earlier, these films are difficult to access and rarely used in history research and teaching. The films are deteriorating and will be lost in a few more years. The Moving Past, then, is also a recovery and restoration project. It hoped these efforts will draw attention to the collection and bolster efforts to preserve them through digitization. Access to The Moving Past is currently open, but this will change sometime later in 2025. There are costs associated with the digitizing of the films, the music syncing and the operation of the site itself that cannot be borne by the author entirely. A low-cost subscription model is being developed to make the site sustainable. This will allow more films to be added on a regular basis, which it is hoped American labor historians will visit.