This year, Punxsutawney Phil saw his shadow on Groundhog Day, which (supposedly) means six more weeks of having to wear your winter coat. In this blog post, CHM costume collection intern Grace Koehler writes about a winter coat that represents retail, manufacturing, and fashion history.

At the turn of the 20th century, department stores played an important role in the economies of urban areas, especially Chicago. These stores originated in Europe and began cropping up in the United States during the 1830s. By the end of the century, they played a unique role in that both their target market and main workforce consisted of women. With the emergence of a middle class brought about by the Industrial Revolution making luxury goods and services more affordable, more women were able to stay home and maintain the household, relying on their husbands to provide. The new industries also enlisted the help of women as workers, and the idea of a woman having a job outside the home also became more acceptable. The department store offered employment for unwed women looking for a relatively “respectable” job in the city and offered a place to spend time (and money) for the married lady with a working husband and a disposable income.

Pedestrians viewing a Marshall Field & Company department store window display in the Loop community area of Chicago, 1910. DN-0008625, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

These stores offered a variety of goods at an unprecedented scale, especially ready-made clothing in fashionable styles for lower prices than those custom made for the wearer. These ready-to-wear garments in department stores and catalogues allowed more people access to rapidly changing styles, or at the very least offered them a chance to replace their worn-out wardrobes. Unlike today, however, the quality and attention to detail on these items was reduced relatively little compared to their bespoke counterparts. Though prices for these clothes were still higher than the cheap price tags on today’s fast-fashion items, those who made the clothing were similarly underpaid and overworked.

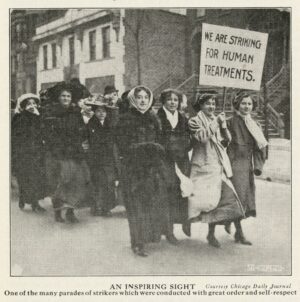

Garment workers on strike, Chicago, 1911. CHM, ICHi-067059

Instead of sourcing labor overseas as is common now, factories employed local working-class women and children, particularly immigrants. Unlike the women working in the department stores, these workers faced harsher conditions and rampant exploitation, particularly since unions and child labor laws were only just coming into play. They must have been efficient and highly skilled to have produced such quality goods at the rate needed to keep up with mass production and consumer demand.

Clothing made for department stores, such as this wool broadcloth coat (c. 1900), are impressive examples of goods made when mass-production was possible, but consumer expectations remained high. The coat has parallel lines meticulously stitched on its yoke and down its front and back, elongating its wearer’s silhouette. The faux double-breasted front is cut straight, and the back lightly fitted to accentuate the fashionable shape at the time and conveniently permitting it to fit wearers in a range of sizes. Large, round mother-of-pearl buttons and dusky brown velvet cross-stitched over the collar provide additional contrast and textural interest. The coat’s slim sleeves and simple, sleek cut stand in contrast to those from about a decade prior, which featured large, puffed sleeves and curve-hugging princess seams.

Left: Fashion illustration titled “Street Costume” by A. Izambard (St. Petersburg) in Coming Styles Designed by the Great Costumers of Europe, fall and winter 1896, published for Marshall Field & Co. by Rand, McNally & Co. CHM, ICHi-037454_h. Right: Sketch of coat on a wearer by Grace Koehler, 2024.

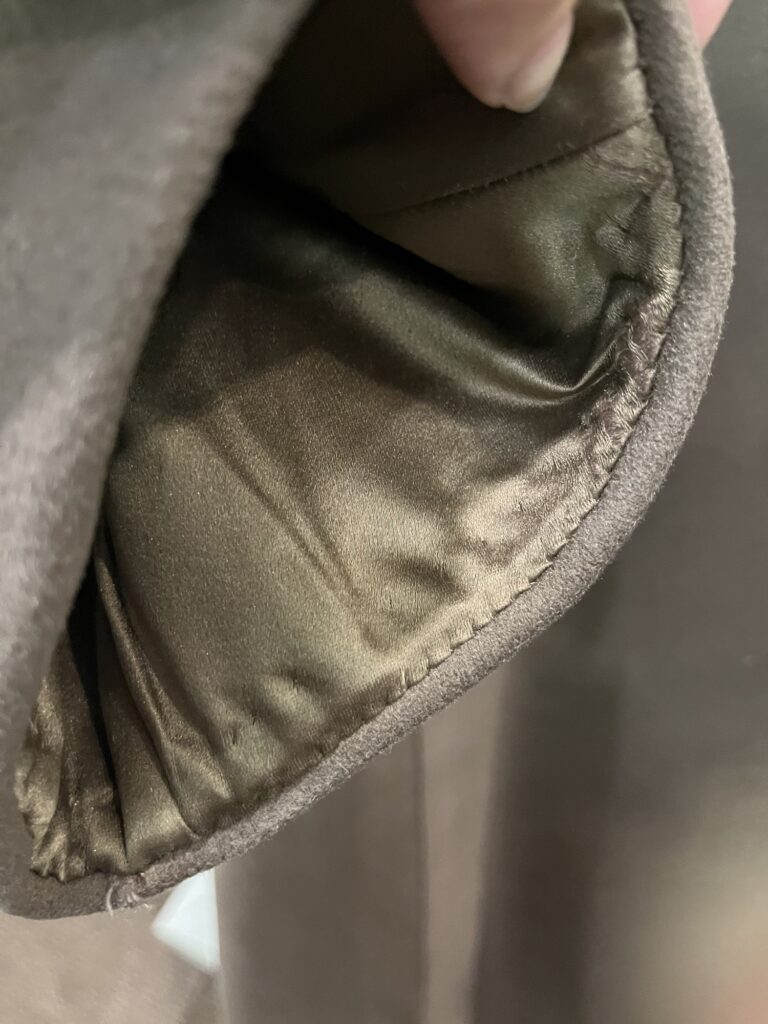

Closer inspection shows the thought put into the needs of the wearer, with a pocket neatly hidden in the self-fabric trim extending from the yoke as well as two breast pockets built into the front facing in a satin matching the fully lined interior. There is also a slit hidden in the back of the coat, also disguised by trim, perhaps to access a back skirt pocket?

The sleeves and hem appeared to be felled down with nearly invisible hand stitches.

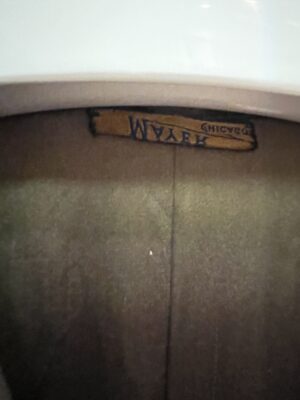

On the inside of the coat at the nape is a label that appears to have been resewn by someone with less deft hands than the coat’s maker, turned upside down and backwards. It reads: “MAYER Chicago.” This coat was most likely purchased from the department store Schlesinger & Mayer.

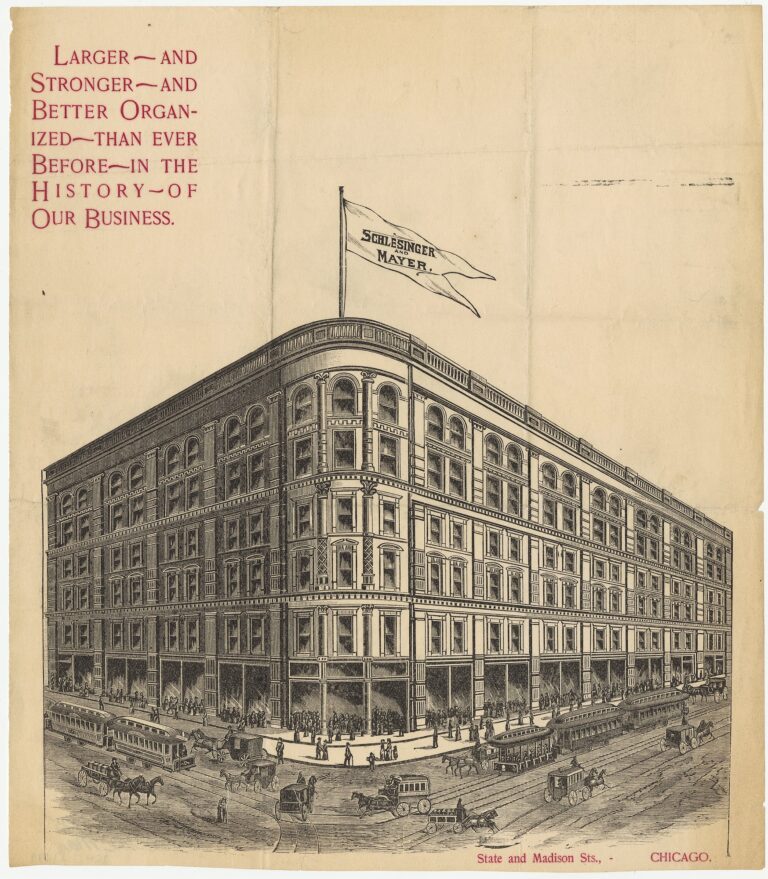

Advertisement for Schlesinger & Mayer, Chicago, 1873. CHM, ICHi-061679

Though the company had existed in Chicago since 1872, they commissioned architect Louis Sullivan to redesign their department store, which employed close to 2,500 people, at the corner of State and Madison Streets in 1899. After its completion in 1904, Schlesinger & Mayer could no longer afford to operate it, so they sold it to Carson Pirie Scott.

The coat’s owner was most likely a woman named Carrie Spooner Case, mother of its donor, Carolyn Case Norem. Carrie, with her husband Francis M. Case, was a Cook County resident around the time the coat was purchased. By the looks of her family photographs, she was an upper-middle or upper-class woman, making her an ideal customer at a department store. She may have visited the Schlesinger & Mayer storefront or flipped through their mail-order catalog until she found a coat that piqued her interest. Regardless, she certainly picked a practical, well-made coat that would last for years to come.