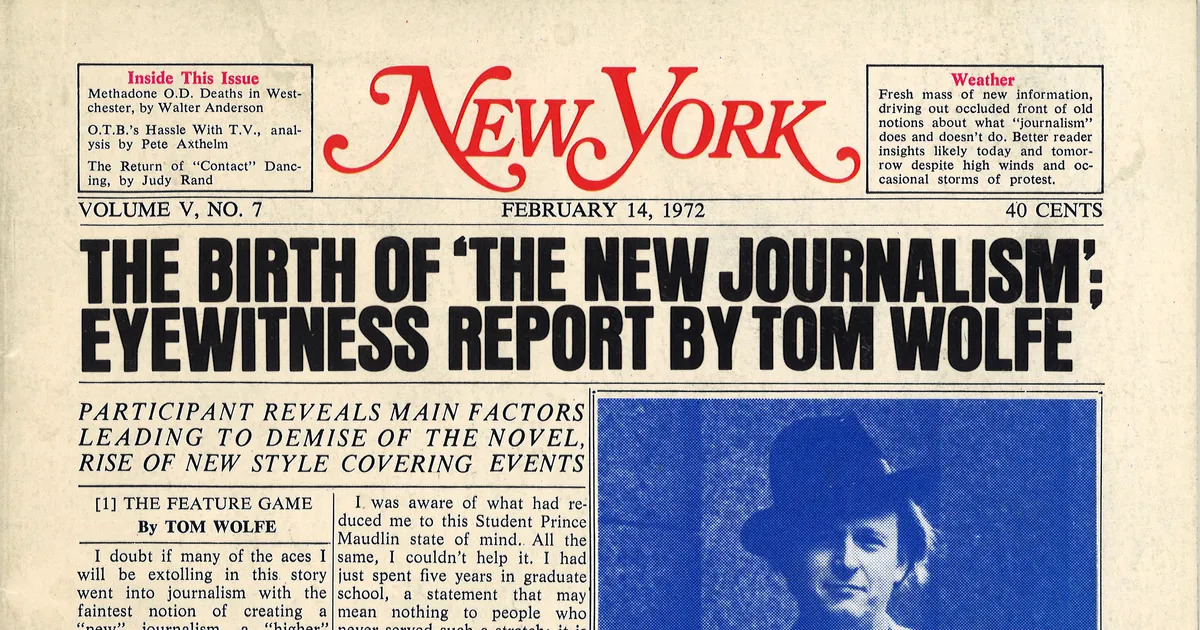

Check out Jeannette Cooperman’s essay at Common Reader on the late white-suited writer Tom Wolfe. She has some interesting thoughts on the so-called “New Journalism” of the 1960s and 1970s.

A taste:

Did Wolfe do such a good job capturing the present that he ruined our future? Consider the trajectory. [Walter] Lippmann urged objectivity in 1920 because he saw “everywhere an increasingly angry disillusionment about the press, a growing sense of being baffled and misled.” He worried about news coming at us “helter-skelter, in inconceivable confusion,” and readers “protected by no rules of evidence.” He was afraid of a time when people “cease to respond to truths, and respond simply to opinions—what somebody asserts, not what actually is.”

Here we are.

In the century between 1920 and 2025, journalists first tried for objectivity, then broke free from convention in the 1960s and 1970s with the New Journalism, named by Wolfe and led by him, Joan Didion, Truman Capote, Gay Talese, and Hunter S. Thompson. The shift would be defined by Marc Weingarten as “journalism that reads like fiction and rings with the truth of reported fact.” Its arrival rang out like a high, clear church bell, elating young feature writers. Its new freedom even colored newswriting, which began to set scenes for us, paint in vivid detail, and smuggle in the first person.

Wolfe was so immersed, observant, and detached that he often got it right. But many of the journalists who followed slid away from the heavy-duty reporting that was the only way to keep New Journalism honest. They learned to write “like” Wolfe, in terms of flourish, without taking the time he took to report the substance. Laden with multiple, rapid deadlines, even the most earnest journalists were unable to climb on a bus and ride cross-country with their subject for a year. Others were wannabe novelists or gonzo reporters hungrier for attention than for accuracy. A succession of journalists were caught plagiarizing; creating composites, glomming various people they had interviewed into a single, named character; hiring other reporters to go to the scene and feed them details; or, not to put too fine a point on it, making shit up.

But good, ethical reporters lost readers’ trust, too. They borrowed New Journalism’s techniques to liven up news stories—which then read like fiction. If someone said of a profile I wrote, “It was like reading a novel,” a thrill ran through me. Once I described the scenery and temperature on a group’s pilgrimage to Israel—interviewing each traveler at length and looking up weather stats and flora and fauna and the colors in the soil and sand—and a friend asked how my trip was. Again, I took this as a compliment. But I was less sure when I gathered bureaucratic background for a local political controversy, watched the long, tedious video of the council meeting, then wrote the piece present tense, carefully setting the scene of the meeting. One official called me and screamed, “You weren’t even there!”

Explaining that scene-setting was a convention of narrative journalism felt a little lame, even to me. Literary techniques make it easy to fudge, and readers sense that.

On the other hand, when someone demanded, “How could you know what he was thinking?” I always had a simple answer: “I asked.” If someone had grilled Wolfe about The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, they would have learned that everything he reported he had either seen or heard himself, found recorded elsewhere, or learned from people who were there. Often if a piece feels vivid and imaginative, people cannot believe it to be accurate. But New Journalism (now old and usually called literary journalism or creative nonfiction) makes the research invisible on purpose. The effort to be artful often means leaving a little wiggle room, not moving in blow-by-blow chronological order or including every detail and caveat. Wolfe’s work crackled with sassy, informed opinion; he was always interpreting, never laying it out flat. Yet he shied away from first-person, pointing out that most of his major writing was “completely about the lives of other people, with myself hardly intruding into the narratives at all. They were based on reporting, so a lot of it is impersonal and objective. It can be discouraging to see it described as implausible, personal, and unbelievable”—just because it is lively.

Read the entire piece here.