This is the third part of our [I, II, I don’t know, a few more?] part series looking at Rings of Power‘s Siege of Eregion from a military history perspective. Last week, we discussed the remarkably bad siege preparation of both sides: Adar’s complete lack of a fortified siege camp and Eregion’s complete lack of scouting arrangements. As with everything else in Rings of Power, both are quite bad by the standards of The Lord of the Rings but don’t matter because nothing actually seems to matter in Rings of Power.

That theme continues this week as Adar begins his attack on the capital, Ost-in-Edhil, opening with a catapult barrage that first defies design sense, before it defies tactical sense, before it defies physics. It really is an impressive encapsulation of so much common broken Hollywood thinking about pre-gunpowder warfare that we’re going to spend an entire post on it.

Now film loves catapults for its pre-modern battle scenes. I think the reason for this is likely to be the enduring influence of post-gunpowder warfare on how film-makers imagine battlefields: something has to take the visual and story place of (gunpowder) artillery, so it has to be catapults. However, as we’ve discussed, the sophisticated siege playbook existed before the invention of catapults and for most siege attackers, a catapult was less a ‘siege winning weapon’ and far more simply a tool to make the engineering tasks that would actually enable an assault easier by suppressing defenders. I think – and we’ll get more into this in the next post – that actual siege tactics could be made dramatically resonant, but filmmakers rarely try, instead reproducing the same handful of lazy and tired battle tropes over and over again.

But first, as always, sieges are also expensive! If you want to help out with the logistics of this blog and my scholarship more broadly, you can support me and this project on Patreon! I promise to use your donations to build some actual working catapults (I actually do have a miniature model of a trebuchet that throws ping-pong ball sized projectiles). If you, like Eregion, completely lack scouts or information gathering of any kind and are thus regularly surprised when posts like this appear outside of your walls, ready to sack your homes free time, you can get a bit more warning by clicking below for email updates or following me on twitter (@BretDevereaux) and Bluesky (@bretdevereaux.bsky.social) and (less frequently) Mastodon(@[email protected]) for updates when posts go live and my general musings; I have largely shifted over to Bluesky (I maintain some de minimis presence on Twitter), given that it has become a much better place for historical discussion than Twitter.

Orc Catapults

Let’s start with the design of the orc catapults. We’ve actually talked in more depth before about trebuchet design and the features back when we looked at the Siege of Gondor, so I don’t want to spend too much time rehashing those points. In this case, Rings of Power has replicated basically all of Peter Jackson’s mistakes with the orc catapults, but without the saving grace of having quite sensibly designed Gondorian trebuchets to offset the problem. So here we have our orc catapults:

But if you had just built out one normal working trebuchet – a task hobbysts do all the time – you wouldn’t have this problem!

Unlike Peter Jackson’s orc catapults, here we have no problem determining the way these are meant to function: they’re counterweight trebuchets, albeit badly designed ones. The way this works is simple: when the long (firing) arm is released, the shorter (counterweight) arm, with its counterweight (the bag of rocks) accelerates downward, with the entire machine functioning as a large lever. The much longer length of the firing arm (anywhere from three to five times longer than the counterweight arm) gives the counterweight a lot of leverage to accelerate the projectile. The greater you can make that difference, the more leverage you can apply, so you want a quite short counterweight arm and a long firing arm.

Now the first problem is that these catapults – which are going to perform very capably on screen – are just visibly shoddily constructed. They’re built, for some reason, from unsawn, unplaned timber rather than planed wood, lashed together with rope. The thing is, the forces that the A-frame of a large trebuchet – much less its firing arm – undergo are considerable, so you want this to be well-constructed and study. Which means you want the joints between the wooden beams to themselves be quite precise and firm: if your frame has a lot of wobble because its only rudely lashed together, that’s lost energy. Catapults were precision machines, the height of engineering in their day and they needed to withstand and direct a lot of force and do so with precision (because you need to hit something with your big rock) and as a result, catapults tended to be quite carefully made. Of course what is absolutely inexcusable here is that if you look closely, the beam (that is, the firing and counterweight arms) are already bending visibly even at rest. If these things can’t stand up to the force of sitting still, I can’t imagine they’ll actually stand up to the force of shooting anything.

Also, I have broken bread with Lee Brice and he never told me he had a class build a working trebuchet, so I feel betrayed.

But design problems don’t stop there: the counterweight is a bunch of rocks, suspended in a bag from what I think we’re supposed to read as a thick, tightly coiled rope. Now I am sure such crude counterweights existed somewhere at some time, but in the historical artwork I’ve seen, the overwhelmingly vast majority of trebuchet counterweights are made the same way: a large, top-topped wooden box, often with something of a bell-shape to it. These are generally suspended just below the counterweight arm by an axle, so they can fall straight down even as the lever rotates. And here I know that these counterweights aren’t designed properly because we can see when they fire that the rope coil (?) remains rigid, meaning that the counterweight doesn’t really drop so much as it ends up twisted under the A-frame.

The reason it seems to be made this way, so far as I can tell, is that the catapults are not tall enough for the length of their counter-weight arm and the long coil of rope that suspends them. As you can see above, if that coil wasn’t (somehow) rigid, the bag of rocks would simply slam to the ground and stop long before the firing arm reached full elevation (assuming the force of the sudden stop didn’t simply shatter the whole thing). Instead, the way real trebuchets handled the forces of firing was to allow the counterweight, once released, to swing freely: the shot was released from the firing rope (we’ll get there in a moment) at the top of the arc naturally, at which point the great weight of the counterweight naturally brings the entire machine to a stop on its own, without any sudden shocks.

Meanwhile, the firing arm is also quite bad. It’s hard to see clearly in most shots – but then, everything is hard to see clearly in most shots of Rings of Power – but the firing arm terminates in what is simply a big iron bowl that is then filled with (burning) rocks:

However, the sling-release on a trebuchet is not really an optional part of the design. The way the sling-release on a trebuchet works is that the sling is attached firmly at one end to the firing arm and on the other end is held in place by a pin which it can slip off of. As the firing arm reaches the apex of its swing, the forces naturally push the pin-end of the sling off of the pin, opening the sling bag and releasing the projectile on an ideal arc. Making the sling longer so that it can rotate around the end of the firing arm even as that rotates around the axle of the trebuchet, allows for more time for the projectile to accelerate along a wider arc and thus more energy to be imparted. But what I want to focus on here is the release part of the release.

Because these catapults do not have a ‘stopper bar’ the way that the Siege of Gondor catapults did, there’s nothing to make the arm stop while the projectile keeps going. Given the deep buckets, it seems pretty likely that the end result here is going to be a catapult that fires its rocks directly into the ground a short distance in front of the catapult as rather than getting a nice, high arc of fire, by the time the projectile exits the bucket (in this case, now caused by the bucket decelerating due to the counterweight), it is now moving downward on the arc.

The final problem is that these catapults have wheels. Wheeled catapults are a standard in video games, but were relatively uncommon historical and to my knowledge counterweight trebuchets were never wheeled. There are a few obvious reasons why. The first is in the firing process: while the balancing of the lever and the lack of a stop-bar means trebuchets don’t ‘kick’ the way some torsion catapults (the onager in particular) did, you still want a really steady base for the machine, typically accomplished by building a wooden base for the catapult rather larger than the footprint of the A-frame.

But that leads into the second reason you don’t put wheels on this thing: why would you want wheels on it? These machines are very obviously too big to simply roll down the road to wherever you are going to do a siege. Instead, trebuchets were almost always constructed on-site; normally, you’d transport the trebuchet deconstructed (and loaded into carts) and then assemble it on site like a giant Ikea War Engine. That, of course, allows you to design the weapon with a nice, wide, stable base to absorb the forces of firing without any danger that the thing is going to start rolling.

Now to be fair, I get the desire by the showrunners here to have a catapult design that is visibly less refined than the very well-made and evidently working trebuchet models that the Gondorians got in Return of the King. But the result here is a design that I suspect most viewers can recognize isn’t quite right and shouldn’t work well, even if they can’t necessarily pinpoint why. I think there’s an obvious solution to this problem of a less-refined, but still effective version of this machine, on that communicates the power of the orcs in raw numbers: the traction trebuchet.

The popular conception, often mirrored in video games, tends to assume catapults developed from two-arm ancient torsion designed, associated with the Greeks and Romans, to single-armed torsion designs assumed to be common through the Middle Ages (often inaccurately named mangonels), which then coexist in the later Middle Ages with counterweight trebuchets. Part of this error, I think, goes into assuming first incorrectly that catapults were essential for sieges (they were not) that therefore every era after their invention must have some sort of common catapult. But in fact the single-armed torsion designs (the onager) are a mostly Late Roman design, replaced by the more powerful and much less complex traction trebuchet (actually what a mangonel is), invented in China, which reaches the Middle East and Europe in the 6th century. The counterweight trebuchet is then invented in roughly the eleventh century, likely in the Middle East.

Whereas the familiar counterweight trebuchet uses a counterweight to drive the short arm of the catapult, a traction trebuchet uses muscle power, by connecting the short arm to a large number of ropes on which many people could pull on at once. The ratio here still favored the firing arm, so the folks pulling the ropes still had a ton of leverage and with a lot of people pulling at once, traction trebuchets could still hurl large rocks substantial distances, though they were less powerful (but faster firing) than counterweight trebuchets. Having these catapults operated by having a few hundred orcs heaving in unison, I think, would be a pretty striking and memorable scene and one that would reinforce the themes the show is trying to create about Adar’s treatment of his ‘children.’

Instead, we get the standard ‘barbarian catapult’ remix, with a design I am fairly certain wouldn’t actually work – and certainly wouldn’t work well. Which is odd, because these catapults then proceed to do impossible things.

Fire Catapults

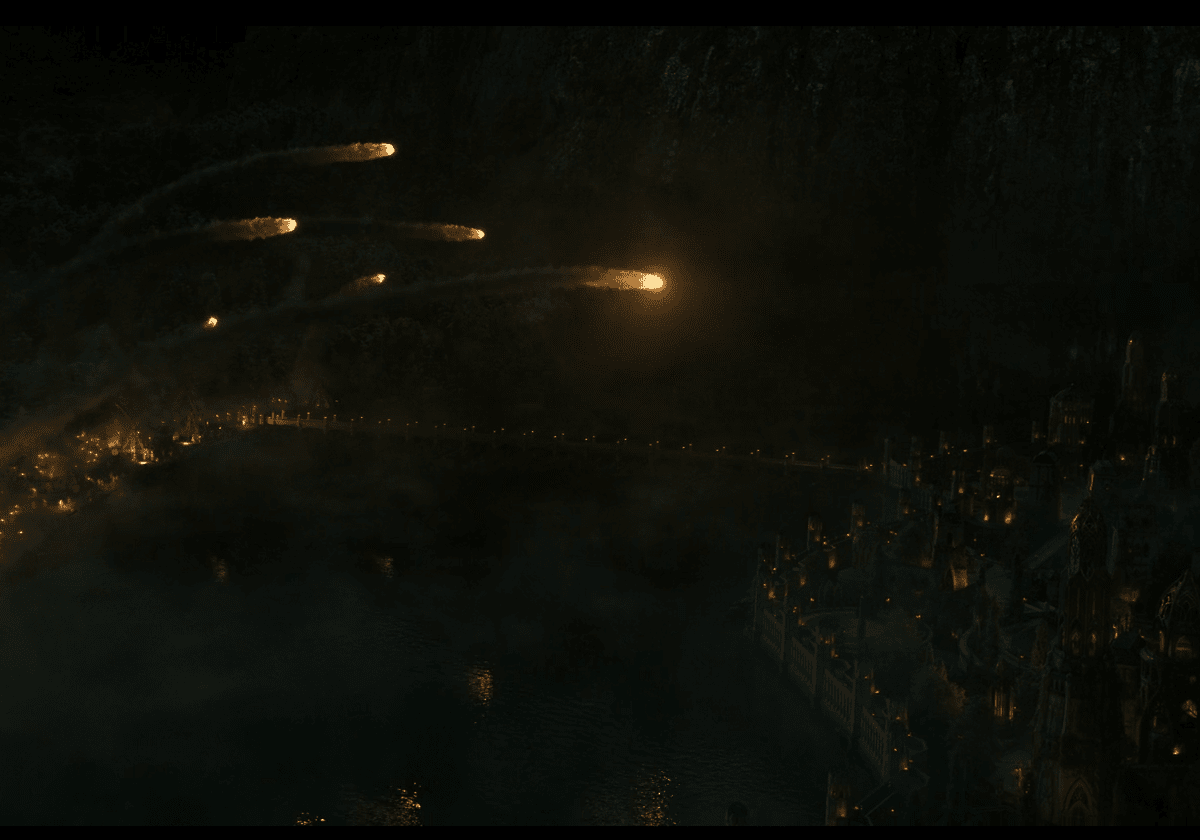

Adar opens his assault by using these catapults to hurl flaming munitions into Ost-in-Edhil, destroying buildings and lighting fires. He makes no effort to try to target the defenses (walls, defensive towers) but instead rains fire directly into the city.

Now, there are two sets of problems here: a tactical problem and a munitions problem. Let’s start with the tactical problem.

Adar’s plan does not involve getting Ost-in-Edhil to surrender. At no point does he, say, demand they just turn over Sauron so he’ll leave. Instead, his very stupid plan from the beginning involves storming the city in the hope that his orcs get lucky and manage, in the sea of fleeing Elves, to accidentally murder the one Maiar-disguised-as-an-elf they’re after. But given that plan, what purpose does bombarding the city for hours with catapults serve?

Now it is the case that during medieval sieges, attackers might intentionally use the high firing arc of trebuchets to fire over the walls, rather than into them. We’ll get to burning projectiles in a second, but this is when you might actually use them: trying to set fire to the densely packed buildings within a walled city or castle. The purpose of doing so was to tie down defenders fighting fires so they couldn’t challenge an effort to breach or scale the walls. But Adar lights the city on fire and then dams the river and then waits for the river to subside, by which point presumably the fires have largely burnt out and then launches his assault.

The other reason to target the city interior would be to demoralize the defenders into surrender. You might, for instance, smash up building and light fires to try to cause so much damage that a town would rather sue for peace than put up with a long siege. Equally, armies might use catapults to fling diseased or decaying corpses over the walls to demoralize defenders and potentially spread plague. But all of that only accomplishes anything if the defenders have an option to surrender (or the siege is going to last long enough that a disease outbreak might matter). That’s not a factor here: Adar has committed himself to a strategy of killing everyone in the city, so there’s little to be gained from surrender and thus little to be gained by trying to demoralize the defenders.

I think the show’s suggestion is that the purpose of this barrage is actually to create lots of smoke in order to darken the skies, though this is never communicated by anyone. Adar looks up at the smoke-filled skies before ordering his catapults to change targets, so perhaps this is what we are to assume. If so, this is an effort to echo the ‘broil of fume’ (RotK 89) used by Sauron to shield his armies from the sun in Return of the King. But Sauron, crucially has a volcano to work with; getting regular fires to equal the amount of dust and smoke a volcano can produce requires massive wildfires burning tens of thousands of acres of forest. Needless to say, a few square miles of city – mostly made of stone – isn’t going to do the job. Sauron is also a magical being with great and undefined powers that might include directing his volcanic ash strategically to cover a region; Adar has no such supernatural abilities. If Adar wants to darken the sky with for his army, he needs to somehow get the entire (quite green and not at all dry) forest behind him burning for something like a dozen miles in every direction and then hope the wind blows the right way (but not too much the right way, or his army will end up feeding the fires rather more directly than intended). Good luck with that.

Meanwhile, we have the munitions problem, which is both that these incendiary catapult shots are absurdly destructive and also that I have a hard time keeping track of how destructive they are – or perhaps more correctly, the showrunners have a had time keeping track of how destructive they are.

In the first case, incendiary ranged weapons – flaming arrows, javelins, and catapult shot – were certainly used on the ancient and medieval battlefield, but as is typical in these sorts of productions, their destructiveness has been vastly overstated. In particular, nothing an ancient or medieval army could hurl would explode, not even the famed Greek fire. For most societies, the incendiaries they were working with were things like pitch, resin and oils (animal or vegetable, not petrochemical). Anyone who has seen a cooking oil fire knows these can, under the right circumstances, burn pretty intensely, but they do not explode: an explosion is not necessarily heat but rather an expanding shockwave caused by a rapid expansion of gasses. You can absolutely have a fireball without an explosion.

As an aside, I think filmmakers tend to blur this distinction because Hollywood tends to love the bright, orange flames of gasoline fires (and the like) to represent all sorts of incendiaries and explosions, both for much less energetic reactions (like ancient or medieval flaming arrows and catapult shots), but also for much more energetic reactions (like modern high explosive battlefield munitions). Modern high explosives of the sort you’d see on a battlefield don’t usually produce much of a fireball at all, unlike in the movies: they’re almost all shockwave and very little ‘fire’ because it is the shockwave, not the heat, of a high explosive that does the killing. But in movies, everything is just a big orange fireball.

Adar’s munitions here are also a Hollywood staple, what I am going to call the “explosive fire-rock” – a catapult munition that somehow maintains all of the smashing power of a super-dense rock while at the same time burning brightly as it passes through hundreds of meters of air to then ignite whatever it touches on the other end, even things – like stone buildings – that are not generally particularly flammable. This is a nice munition to have access to when you have already suspended the laws of physics. We’ll deal with the impact part of this in a moment, so let’s focus on the incendiary component here.

Adar’s shots slam into the city, smashing (or blasting?) apart large stone structures and setting basically the whole city to light. They appear to be shooting large rocks covered with some kind of blackish goo – perhaps pitch. That would…simply be extinguished flying through all of the air they are throwing these things through. In practice, historical incendiaries tended to either be delivered at short ranges and low velocities (to avoid the movement through the air putting them out) or basically as grenades: breakable containers filled with the flammable material with a lit fuse that might break out and ignite on impact (and of course, rarely, sprayed in liquid form, as with Greek fire). The former is actually more common than the later: we see all manner of specialized incendiary arrows and javelins beginning in at least the Roman period, if not earlier: these usually have some design to enable a wrap or cord soaked in something flammable oils or pitch to be wrapped around them, ignited and then shot.

These sorts of incendiaries had pretty sharp limits: the amount of thermal energy they could deliver wasn’t all that high, meaning they were only going to set something on fire if it was already fairly flammable. Fortunately for ancient and medieval pyromaniacs, their ships were built of wood and cities were often mostly wooden buildings, roofed with very flammable thatch. It might still, with these weapons, take quite a few tries to get anything to actually catch fire, but in a siege context the attacker had more than enough time to keep trying to get a fire going which would then become a distracting liability for the defender.

Instead, Adar’s catapult shots are so destructive they reduce large stone towers to piles of brightly burning rubble, apparently almost immediately. Here, for once, we do have something of a ‘clock’: Adar begins his barrage at night and by morning apparently has enough smoke to contemplate an attack on the city. Or, in a piece of the show’s tremendously bad writing, a “ground assault” (Sauron’s words) which raises the question of what other kinds of assault are there in Middle Earth? Were the Elves of Eregion otherwise preparing for an orcish air assault? So in just a few hours, Adar raises a sky-blocking curtain of smoke and reduces much of the city to rubble, as we see here:

Except wait, does he? Because Arondir shows up three minutes (of screentime) after that shot of ruined, burning towers and looks out at the city – the river now draining – and sees this:

Apparently just a few scattered fires, a number of smashed roofs, but most of the city still standing just fine, with relatively little smoke and no damage at all to the city’s fortifications (something we’ll return to next week because this is what the catapults ought to have been doing). I realize we’ve already had respawning orcish armies, but I think a respawning Elvish city may be a bit too much. In any case, these sorts of scattered fires and limited smoke are rather more what I’d expect a barrage of pre-modern incendiaries to produce, rather than the enormous damage we see in the scenes preceding this.

But I think it speaks to the degree to which these weapons and their effects aren’t being treated as real by the showrunners: they’re merely events in a script. So they appear and seem to accomplish something (the burning destruction of large portions of the city) which then vanishes two scenes later, because the folks making the show don’t seem to feel the need to maintain the sense that this is a real physical place where, for instance, massive destruction in one scene ought to still be reflected in the next. The problem that poses, of course, is a loss of the sense of physical consequence. Adar’s army respawns, humans and Elves walk unharmed out of volcanic eruptions, armies teleport around the world: nothing matters. And if nothing matters…why should we care?

But of course we also have to talk about:

Dam Catapults

However much of the city Adar was going to burn, once he is finished burning it, he turns his catapults away from the city. His plan is to enable a breaching attack by draining the riverbed of the Sirannon, by using his catapults to collapse a stone mountainside to make a dam.

By which point, yeah, if Adar has shown up with the main battery of HMS Majestic (1894), I think he may be able to bring down this mountain but also at that point, probably doesn’t need to.

Just about every part of this plan seems to defy physics and worse yet – as we’ll get into more next time – the whole thing is entirely unnecessary as there’s a much easier way to get over the river and to the base of the wall.

First, we need to start with the catapults. Fantasy filmmaking in general has a hard time keeping straight how powerful even the largest catapults – like large, counterweight trebuchets – are and how to express that visually. As I noted back in the Siege of Gondor series, Peter Jackson himself struggled a bit with the physics of catapults and their ranges and shot-weights. But the upshot of all of this is that trebuchets are not gunpowder artillery and do not have anything like the range and power of even relatively early gunpowder artillery.

We have a range of estimates for the range of late medieval counterweight trebuchets – the largest, most powerful catapults built – both from historical reports as well as from modern reconstructions. Sources report large counterweight trebuchets throwing 100kg projectiles 400m and 250kg projectiles around 160m. That’s quite a bit of distance for some very big rocks. The Warwick Castle trebuchet, a modern reconstruction, was in theory designed to throw projectiles up to 150kg up to 300m; its record shot was a 13kg projectile hurled 249m with a launch velocity of 55 meters per second, but I’ve seen higher launch velocities, as much as 70m/s reported.

Now, launching a 150kg projectile at 70m/s is quite impressive. If that hits you, it is going to hurt quite a lot. But we want to put both the range (150-400m) and the energy into perspective.

The first thing we want to note is the range, which you may note is suspiciously just a hair beyond effective bowshot. That’s not an accident: your catapult loses power the more of its range it has to use (because these big projectiles are slowing down in flight) so to smash walls, towers and crenelations, you want to get your catapult as close as possible, and so you’re designing for what is, effectively, the closest safe range. Naturally that is going to mean ‘just outside of bowshot’ since a bow is the longest ranged weapon the defenders can use short of having their own catapult. ‘Bowshot’ as a distance varies based on the bows and archers used, but for the very best bows, effective bowshot – where arrows retain substantial lethality – fades out around 200m.

Two hundred meters certainly isn’t no distance at all, but it isn’t the miles of range we generally see catapults fire at in film. 400m, after all, is just 0.4km or just about a quarter of a mile. A fit person can run that distance in under two minutes. That of course has implications which loop back to our lack of circumvallation: siege engines cannot be placed so far from the enemy as to be beyond fear of attack. At 200-400m, the attackers do, in fact, have to worry that an enemy might suddenly sally out, dash the one to two minutes it takes to reach the catapult, overwhelm the defenders, destroy the catapult and dash back in before the full force of the besieging army could respond. That’s precisely the sort of thing your own field fortifications are meant to prevent.

The second point is about the amount of energy these catapults are delivering. To take something like the Warwick Castle Trebuchet – which is, I should note, quite a big example of the type and so serves as an ‘upper end limit’ to a significant degree – a 150kg projectile launched at 70m/s is leaving the sling with an impressive 367,500 joules of kinetic energy (though of course it won’t deliver anything like that many to the target, because of air resistance and the high firing arc). That is massively more than the launch energies of war bows – around 80-150 joules.

But it is a lot less than gunpowder artillery. How much less? To take a late example – because I can find complete statistics on it – the M1857 12-pounder ‘Napoleon’ (Canon obusier de campagne de 12) was a middle-weight field gun, much smaller and lighter than the siege guns of its day, and fired a 12lbs (5.4kg) shot with a muzzle velocity of 453m/s. That’s 550,000 joules for a relatively light field gun. It could throw that shot, by the by, 1,500m. Finding reliable ranges and muzzle velocities for earlier siege cannon is more difficult; Mons Meg, a 15th century siege cannon, fires a 160kg projectile with an estimated muzzle velocity of 315m/s – firing at a staggering 7,938,000 joules, a full order of magnitude more energy than the largest trebuchets.

The Meg that Says, “No, you shut up.“

(By the by, this is a great example of a hoop-and-stave cannon, an early production method of building up the barrel of a gun).

And we know that is basically right, because whereas the invention of the trebuchet did not really force any great revolution in castle design (castle walls get a bit thicker, but only marginally so), the arrival of gunpowder artillery in Europe absolutely did, because relatively thin castle walls that could stand up to trebuchet strikes simply could not stand up to cannon fire. The point of this exercise being: if your frame of reference for the destructiveness of artillery is gunpowder artillery, you are going to vastly overestimate the range and power of trebuchets and other catapults.

Which of course brings us to the point I suspect most people realized simply by watching this scene: there is no way these trebuchets can even get a projectile this far, much less this high, much less with the power required to actually cause any kind of collapse. Having had to watch this scene a few times, you can actually see this quite clearly in watching: the stones come off of the catapults at angles far too low to get very high up on the mountain and then when we see them flying, their trajectories are pretty clearly impossible – they seem to float upwards like leaves carried by the wind, rather than like very heavy objects moving in ballistic arcs. Meanwhile, it takes a LOT of energy to move a mountainside made of solid rock.

At the very least, even with his cannon-pults, it is going to take Adar a long time to collapse the mountainside, especially because counterweight trebuchets are quite slow firing, taking anywhere from half an hour to an hour to fire once. The reason for this is pretty simple: all of the energy of a counterweight trebuchet is still coming from muscle power – it is merely being stored in the counterweight. After all, it is muscle power that is going to lift that counterweight into the air. And naturally, if you have a bunch of humans putting a couple hundred thousand joules of kinetic energy into that counterweight, it’s going to take them a while (and a way to get a bunch of mechanical advantage). So each of Adar’s catapults is delivering relatively little energy (those rocks are impacting at the top of their arcs, so they’ve lost a lot of speed) and quite a slow rate. In practice, I suspect long before Adar would have dammed the river just by filling it with large rocks long before he triggered a cliff-face collapse. In a note that will become a theme next week, Adar would have been much better served by sending orcs with pick-axes and shovels to simply fill the river.

The worst part is, even if Adar somehow had high explosive ground-penetrating ‘torpedo shell’ catapult shot that he borrowed, presumably, from the First World War, this plan still wouldn’t work!

The idea here is to dam the river in order to enable his army to cross it to reach the wall. Now, there’s already the problem that damming the river doesn’t create dry flatland but silted, wet riverbed, which would be terrible ground to try to attack across (but more on that next time). But we don’t even reach that problem. Damming a river does not make the water go away, it merely begins to back up behind the dam, the water-level rising until it surmounts some part of the dam and begins discharging again. This is a very big river so that water is going to build up behind this makeshift dam very quickly. I suspect in actual practice, it would violently wash those stones away – or at least enough of them to force a passage – and Adar would have succeeded in creating rapids, not a dam (and still be very much stuck on his side of the river, but now with better options for higher difficulty white-water kayaking).

But assuming the effort to dam the river somehow succeeds, the water has to go somewhere. Now, what we see is the dam comes down between the shoulders of two mountains (so upriver, ever so slightly from the city), so the water is simply going to rise until it gets over the dam (which is a lot lower than the mountains) and then overflows the dam…right back into the riverbed. How quickly this happens, I suppose, depends on the height of the dam; I am not a hydrologist. But my sense here is that Adar is unlikely to be able to actually drop rocks in this river faster than the water level rises, which is to say I don’t think he’s going to get much – if any – window of dry passage to the walls. Eventually, if his dam is high enough, the water will instead discharge into the city, which would be bad for the Elves (though the city backs into the mountain, so they have high ground to go to) but also bad for Adar, because all he’ll have managed to do is move the impassable river to a spot where there are no bridges and where the rapid flow and choppy water behavior make building one nearly impossible.

Conclusion

Ironically, with a little planning ahead, this plot point might have been fixed. Instead of placing a dam upriver from Ost-in-Edhil, you could have placed a large dam downriver and have Ost-in-Edhil sitting on the reservoir that created. Adar could then blow the dam, rapidly draining out the resevoir and perhaps reducing a vast lake to a small enough stream that it could be forded. But of course this is, as you will recall from last week, a series that forgot in Season 1 to add walls to the city they were going to do a big siege sequence of in Season 2, so that kind of planning is almost certainly out.

Instead, to my mind the underlying ‘sin’ here is once again the attempt to be ‘clever’ with tactics and try to surprise the audience. I wonder if this isn’t an effort to recreate memorable moments like Saruman’s blasting the Deeping Wall or Tyrion’s use of wildfire in the Battle of the Blackwater. But – and brace yourself because I am about to say something nice about Game of Thrones – those moments work because they make sense and they make sense because they are based on actual historical tactics. Undermining and using explosives (like black powder) was a standard feature of siege warfare from the early modern period through to the First World War (and almost certainly more recently). Likewise, I suspect the inspiration for something like the Battle of the Blackwater lies in Byzantine use of Greek fire to defend Constantinople, as with the 7th century Umayyad siege of the city. While the fantastical setting can heighten the event – Westerosi ‘wildfire’ is even more destructive than Greek fire, for instance – it remains grounded because it is grounded in a historical event.

But that means the best way to create believable moments of surprise for an audience, where a character can be shown to be innovative by having them be innovative, the best way to do that is to read a whole bunch of history! It is to develop a familiarity with historical tactics and weapons, so that you have a scrapbook of historical tactics you can draw on and heighten for these key moments. What I always find so striking is that these ‘clever’ a-historical solutions both batter suspension of disbelief but are also a lot less actually clever than the historical solutions. Actual siege-craft required a lot of specialist know-how and often a lot of engineering to produce fairly clever solutions: armies collapsed walls by undermining, tunneled under them to gain access, suborned traitors to sneak in, damaged gatehouses so they couldn’t close, built pontoon bridges to cross water, towers and ramps to access walls and systems of defensive barriers (mantelets) to be able to safely approach walls. All of those ‘neat tricks’ are interesting and plausible (because they actually happened). But you have to study history to know about them!

What I am going to do now is watch The Empire Strikes Back, to wash away the taste of Rings of Power.

Next week, as Adar begins his “ground assault” we’ll look at some of the clever engineering a historical army might have employed to try to crack the defenses of Eregion.