Preface for Not Even Past: What place do video games have in the history classroom? Until recently, most educators dismissed this medium as frivolous and sensational. But given the staggering time that students spend in these digital landscapes, and the increasing thoughtfulness and diversity of major games, it may be time for a reassessment.

My own experience in teaching a college class on late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century American history through the Red Dead Redemption franchise has convinced me that there’s tremendous future potential in the intersection of games and serious history. My experimental course at the University of Tennessee has seen unprecedented enrollments each semester, and student enthusiasm during class has similarly shot upward.

I’ve adapted the course into a book, Red Dead’s History, which has also convinced me that digital games can provide a bridge for professional historians to reach wider audiences and share the academy’s wealth of knowledge. The book has granted me opportunities for public engagement that I could never have imagined previously – many made possible by my audiobook’s narrator, actor Roger Clark, who played Red Dead Redemption II’s protagonist. Roger and I spoke to a packed auditorium at San Diego Comic-Con, and were interviewed by one of YouTube’s most popular game streamers. When Roger and his fellow actor Rob Wiethoff made a surprise visit to my college class, game news site IGN broadcast the footage to millions of viewers.

While this short-form public engagement often lacks the depth that academic scholars are accustomed to, it leads viewers toward a book that is very much a scholarly product, as Red Dead’s History is a synthesis of recent historiography in U.S. western, southern, and Appalachian history. And as early reader reviews indicate, new audiences are finding that scholarship fresh and illuminating. As video games continue their astronomical growth in future decades, historical games will remain central to the medium. How will professional historians leverage this public passion toward serious study of the past? The future is wide open

This article was originally published in “The Conversation” on 7.19.2024.

Q: What prompted the idea for the course?

This course was born during the COVID-19 pandemic. Confronting the lockdowns of 2020 and uncertain months spent at home, I rekindled a high school hobby that I had neglected for two decades – video gaming.

One of the first games I picked was “Red Dead Redemption II,” set in a fictionalized America of 1899. The game follows the Van der Linde gang, a diverse crew of idealistic outlaws, as they flee authority in an increasingly ordered and hierarchical world. Since its 2018 release, the game has sold more than 64 million copies, making it the seventh on the list of all-time bestselling video games – and the only historically themed one on the list.

While video games had been a mindless pastime in high school, this time around, I was playing as a professor who specialized in U.S. history since the Civil War. And though that made me a far more critical gamer, I was also genuinely surprised at how often RDRII – as it is often called – alluded to major topics that historians have spent generations debating.

These topics include corporate capitalism, settler colonialism, women’s suffrage, and the inequalities of race in an era that Mark Twain had called the “Gilded Age” – a period where the dazzling wealth of a small handful sharply contrasted with the misery of common people. These weighty topics were often on the game’s sidelines rather than at center stage – but they were present nevertheless.

Q: What does the course explore?

Given the centrality of violence to the video game, the course seeks to understand what really spurred bloodshed in the United States between 1865 and 1920.

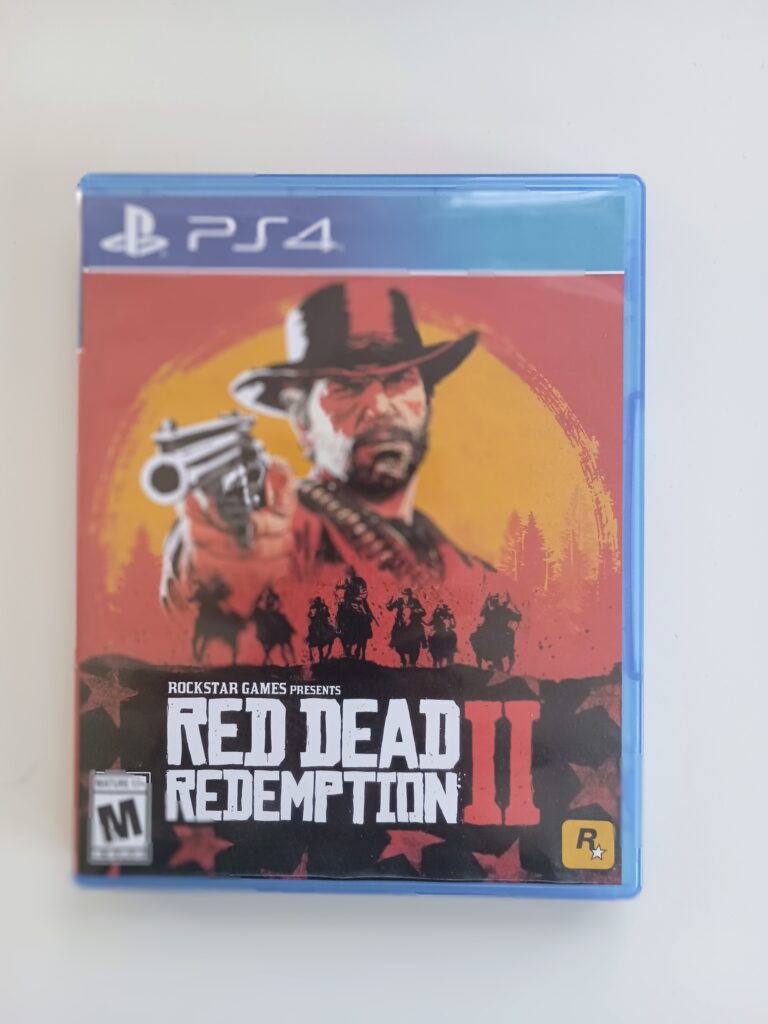

In RDRII, gunfire is usually sparked by personal grudges, robberies, or the overconsumption of alcohol. But in Gilded Age America, it wasn’t so simple. Instead, broader social problems were the primary catalyst of violence. First, Americans fought over the emerging regime of corporate capitalism. Should new businesses like U.S. Steel and the Union Pacific Railroad, who wielded never-before-seen power and influence, dominate workers and consumers alike? Many resisted such an idea through protests, strikes, and sometimes bloodshed.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Secondly, Americans came to blows over the unfulfilled promises of racial equality that were written into the U.S. Constitution after the Civil War. Especially in the South, where the vast majority of African Americans lived, the formerly enslaved and their descendants demanded inclusion in politics and a chance to progress economically. But many white Southerners resisted such efforts, often using terrorism to push their Black neighbors into subservient positions.

Q: Why is this course relevant now?

American society in the late 19th century was ruptured by inequalities wrought by capitalism and race – and so is ours today. In the wake of Black Lives Matter and Occupy Wall Street, it’s wise that we look back at the long road that brought America to its contemporary dilemmas of racial violence and the gap between rich and poor. A handy way to open that conversation with young Americans is through video games – an industry that has now surged in value to eclipse both music and movies and which might be the key to reaching this generation’s students, as studies are beginning to show.

Q: What’s a critical lesson from the course?

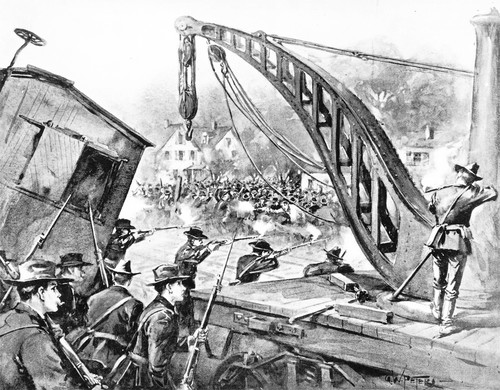

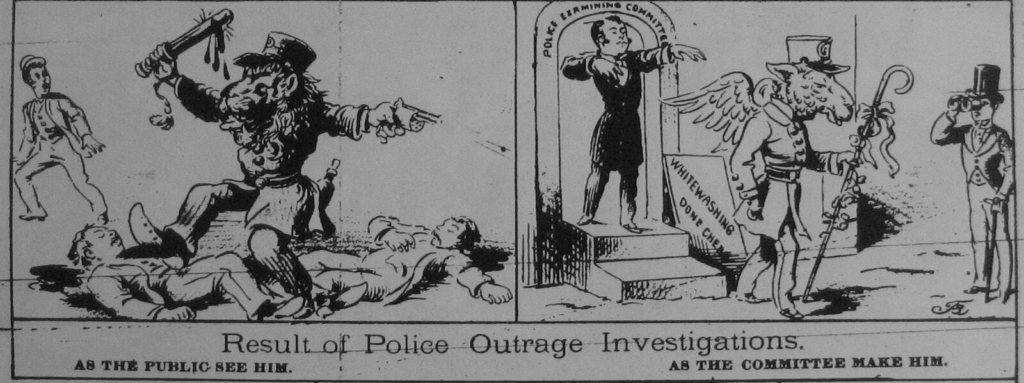

One key lesson is about the city of New Orleans, fictionalized in RDRII as “Saint Denis.” In the game, the outlaw protagonists trade fire with the city’s blue-coated policemen following a botched bank robbery, leaving bodies in the streets. Few gamers could guess that a similarly bloody firefight with the police riveted the actual city in 1900, just a year after the game is set, leaving seven officers dead. Yet here the outlaw was a Black man, Robert Charles, who took a violent stand against police abuse and the emerging system of Jim Crow segregation.

In response to his attacks on the police, white mobs roamed the city and indiscriminately killed Black civilians. Therefore, the explosion of violence in New Orleans was produced not by simple banditry but by one of America’s towering social dilemmas.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Q: What materials does the course feature?

I frequently begin course sessions with a brief video cutscene or gameplay footage from RDRII before we dive into the actual history that the games represent – or sometimes, misrepresent. For reading, students dive into scholarly monographs such as historian K. Stephen Prince’s “The Ballad of Robert Charles,” on the violent dilemmas of race in New Orleans. They also read various original sources, such as cowboy memoirs, train schedules, and a Texas newspaper from 1899.

Q: What will the course prepare students to do?

Anyone who has taken my class – or read my new book – will know that the big social problems we are wrestling with today have deep roots and took their modern shape during the same 1865-1920 period that is memorably captured in RDRII. They’ll also become much more discerning consumers of digital media and games in particular; they’ll be better able to assess and critique representations of history on the digital screen.

Tore Olsson is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Tennessee.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.