A little backstory. For the last few years, I’d been thinking a lot about Phil Mulloy’s snarky films. Why? Because satirical attacks on society were lacking in animation, with animators becoming increasingly insular, turning the gaze a tad too intensely on themselves, and assorted neurodivergent issues. All of that is fine and necessary, but I kept wondering: where were the animators staring outside at the chaos around us?

Those thoughts came and went over the years, but it was when Animafest Zagreb gave a lifetime achievement award to Mulloy in 2024 that I decided… Okay, enough, let’s write a book about him.

So I did — and because of that, I was lucky to have seven or eight hours of conversations with Mulloy this past winter. In March, he told me he was sick. I was asked to keep it private, and honestly, I had no idea how treatable or serious it all was anyway.

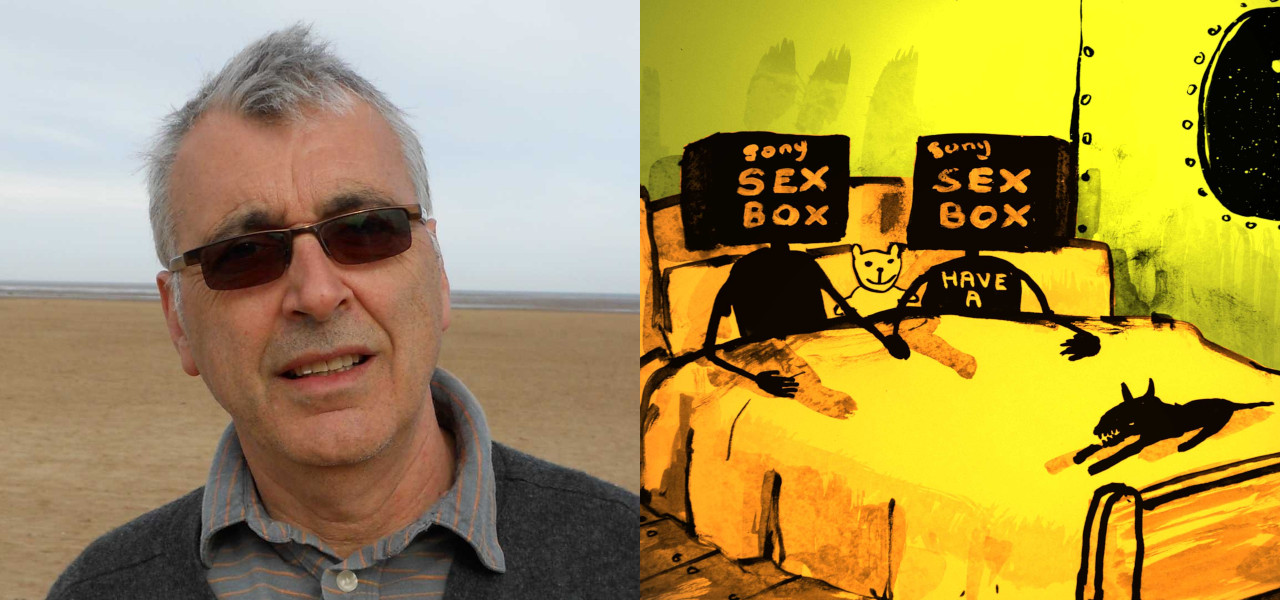

Phil Mulloy died on July 10, 2025, at age 76. He leaves behind a unique, provocative, and unyielding body of animated films that relentlessly challenged societal norms, exposing hypocrisies in religion, politics, and culture with raw, minimalist aesthetics and biting wit. Mulloy was animation’s provocateur—a satirist who wielded ink and paper like weapons, confronting viewers with uncomfortable truths in a medium too often associated with comfort and innocence.

Born in Wallasey near Liverpool on August 29, 1948, Mulloy’s early years were marked by the strict discipline of the Irish Christian Brothers at St. Anselm’s College, an experience that forged his lasting skepticism toward institutional authority and moral hypocrisy. He later described these formative years succinctly: “Anything that beats you into submission, you question forever.”

Though initially inspired by copying Disney cartoons, Mulloy quickly abandoned polished mainstream aesthetics. His awakening as an artist came during his years at Wallasey Art College, where he began exploring intense, unsettling imagery—a passion further fueled by discovering Picasso’s raw woodcuts during a pivotal trip to Paris. At the Royal College of Art in London, he created his first animated short, Allow Me (1970), a stark, energetic blend of live action and spaghetti-style animation, but soon turned away from animation, disillusioned by the laborious process.

After nearly two decades working in documentaries and live-action shorts, Mulloy returned to animation in 1988, encouraged by his wife, animator Vera Neubauer. Working alone in a barn studio in rural Wales, equipped only with paper, ink, and a salvaged Steenbeck editing machine, he created Eye of the Storm (1989), a nightmarish meditation on childhood fears, using accidental sounds and first takes to maintain authenticity. “All I needed was paper and a camera,” Mulloy told me. “I didn’t have to please anyone.” This return marked the beginning of his uncompromising method: no storyboards, no re-draws, no polishing of edges. Mistakes, Mulloy insisted, “are part of the work. They’re the truth.”

His breakout came with the Cowboys series (1991), comprising six fierce, three-minute shorts drawn in jagged black ink. Through brutally minimalist imagery and dark humor, Cowboys dissected toxic masculinity, mob mentality, and media-induced violence. Mulloy described it as “animation as punk rock,” a statement of rebellion against the smooth aesthetics that dominated the medium.

The Sound of Music (1993), not to be mistaken for Rodgers and Hammerstein’s classic, followed soon after, a grim satire of class inequality viewed through the lens of a window cleaner named Wolf. Alex Bălănescu’s edgy violin score underscored scenes of grotesque indulgence and hidden cruelties.

Between 1994 and 1996, Mulloy produced The Ten Commandments, a series of ten razor-sharp shorts in which his skeletal figures struggle with each biblical commandment. Mulloy explained that these shorts weren’t mere provocations but moral mirrors designed to highlight society’s absurd contradictions. They underscored his belief that true morality lies not in rigid doctrines but in the genuine complexity of human behavior.

At the turn of the millennium, Mulloy began the ambitious Intolerance trilogy (2000–2004), which he described as a spontaneous creative eruption: “I just started drawing, and one film became three.” Over more than seventy relentless minutes, Intolerance foresaw a society saturated by conspiracy theories, misinformation, and spectacle. In it, alien Zogians invade Earth to expose humanity’s bigotry, cosmic warfare intersects with pornography, Olympics distractions hide underlying fanaticism, and ultimately, reality itself becomes a distorted farce involving Elvis worship and Disneyesque torture. Mulloy’s prescient satire prophetically anticipated the cultural anxieties of the coming decades.

His next major project was The Christies, beginning in 2006 and extending into a trilogy that combined surrealism, dark comedy, and scathing family drama. Eleven shorts commissioned by the BBC became a profoundly uncomfortable feature about a grotesque family whose lives were caricatures of societal decay. Goodbye Mister Christie (2008), Dead But Not Buried (2010), and The Pain and the Pity (2013) formed a biting meta-commentary on narrative, authorship, families, and societal obsessions.

Mulloy’s final period was highlighted by the short films Endgame (2015) and Once Upon a Time on Earth (2023), which explored war, climate crisis, and societal complacency.

Mulloy had almost always been his own producer, crew, and audience. It was a lonely but fiercely independent space. “It was just me,” he recalled. “I wanted to make something. I wanted to say something. But I also wanted it to be simple. I never knew where it was going. Sometimes you went down the wrong street and had to walk back. But then you put the sound on, and it came alive.”

Even as he shifted styles—cowboys, commandments, Zogs—he often kept the same black-and-white visual rhythm. Not out of stubbornness, but because it freed him up. “It was like handwriting,” he said. “I didn’t need to think. I could just turn it out.”

But eventually, he knew he needed to change. The Christies were a turning point: color, new textures, looser rules. “I thought, I’ve kind of milked this cow,” he said, deadpan. It was a classic Mulloy line—dry, self-aware, a little dismissive, but with real clarity underneath. He’d pushed one approach as far as it could go. Now it was time to move on.

So he made things even simpler. “I thought, go the whole hog—give them nothing. Let the audience do the work.” He found constraint opened doors. “You can make humor if you set very tight parameters,” he said. “You came up with solutions I found fascinating.”

But digital tools came with their own challenges. “Everything’s smooth now. I liked things that flickered and jumped. I found them more alive.”

There was something punk about his resistance to polish. Not in style necessarily, but in spirit. He resisted gloss. Resisted ease. Resisted anything that made the work too clean, too safe, too predictable.

And he was deeply uninterested in the machinery of the industry. “These days, it all comes out of graphics. I came from painting—experimenting, trying things out. It was looser.” The idea of a packaged script, pitched and polished? “I thought that was kind of foolish.”

Money had never been the motivator. “Maybe I was an idealist,” he once said. “I tried to keep my work free from money—filthy lucre. I was more interested in earning money in other ways, separate from my work.” Even back when arts funding was more generous, he often sidestepped it. “I didn’t get any money for Ten Commandments. I just made them.”

There was a stubborn freedom in that. It meant making the film was the reward. The process was the point. “If you wanted that kind of freedom—where you didn’t need a script, where you could just go somewhere and see where it took you—you had to work differently.”

And that’s what he always did. Worked differently.

Still, there was a limit to what satire could do when the real world became its own grotesque cartoon. “It was like a satire of itself,” he said. “But it was a satire that was also a threat, which made it pretty scary.” His work had gotten bleaker. More stripped down. Less pointed commentary, more existential dread. “I’ve always been bleak,” he recently recalled, almost proudly.

But it wasn’t cruelty. It was critique. “Everything I did, even if it was aggressive, came from a place of calling out how things were organized. It wasn’t against people. I wasn’t interested in putting down the little man.”

And maybe that was the thread. Across all the films, from the raw ink-splattered early shorts to the darkly formal Zog sagas, Mulloy tried to strip things back. To scratch off the surface and look at what was underneath: the systems that shaped us, the habits we repeated, the rules we didn’t even realize we were following.

It was clear, though, that the shift to digital tools had changed the tone of his work. Phil wasn’t blind to the advantages that technology brought—sophistication, smoother results, more control—but he always resisted the sheen that came with perfection. “Everything in digital cinema was smooth now,” he said, with a note of frustration. “I tried to prick that bubble of slickness. To show what was underneath.” For Mulloy, the simplicity, the rawness, the flicker of imperfection—it was where the pulse of the work lived. He didn’t want the polished surface that digital could deliver. He wanted something with a little more life, something with edges, something you could feel.

It was a statement on the nature of art, and maybe on the world itself. There was something inauthentic about the constant push for smoothness. For perfection. Mulloy didn’t have time for it. Not when there was something raw, something underneath that needed to come out. In times like these, that underneath—whether it was in the work, or in the world—deserved to be seen.

Mulloy is survived by his wife, Vera Neubauer, and their children, Daniel and Lucy.