For decades, the story of how human pigmentation changed as Homo sapiens spread across Europe has been told in broad strokes. Early humans arrived from Africa with dark skin, and as they adapted to lower UV radiation in northern latitudes, their skin lightened—a simple narrative of evolutionary selection. But a new study, conducted by researchers at the University of Ferrara and published as a preprint on bioRxiv, challenges this oversimplified account. By analyzing ancient DNA from 348 individuals spanning 45,000 years, the researchers have reconstructed a far more intricate picture—one in which light pigmentation emerged gradually, in fits and starts, rather than in a smooth, inevitable progression.

Using a probabilistic genotype likelihood approach, the researchers examined DNA from well-known ancient specimens, including the 45,000-year-old Ust’-Ishim individual from Siberia and the 9,000-year-old SF12 from Mesolithic Sweden. Their goal was to infer eye, hair, and skin color from genetic data while accounting for the challenges of working with low-coverage ancient DNA.

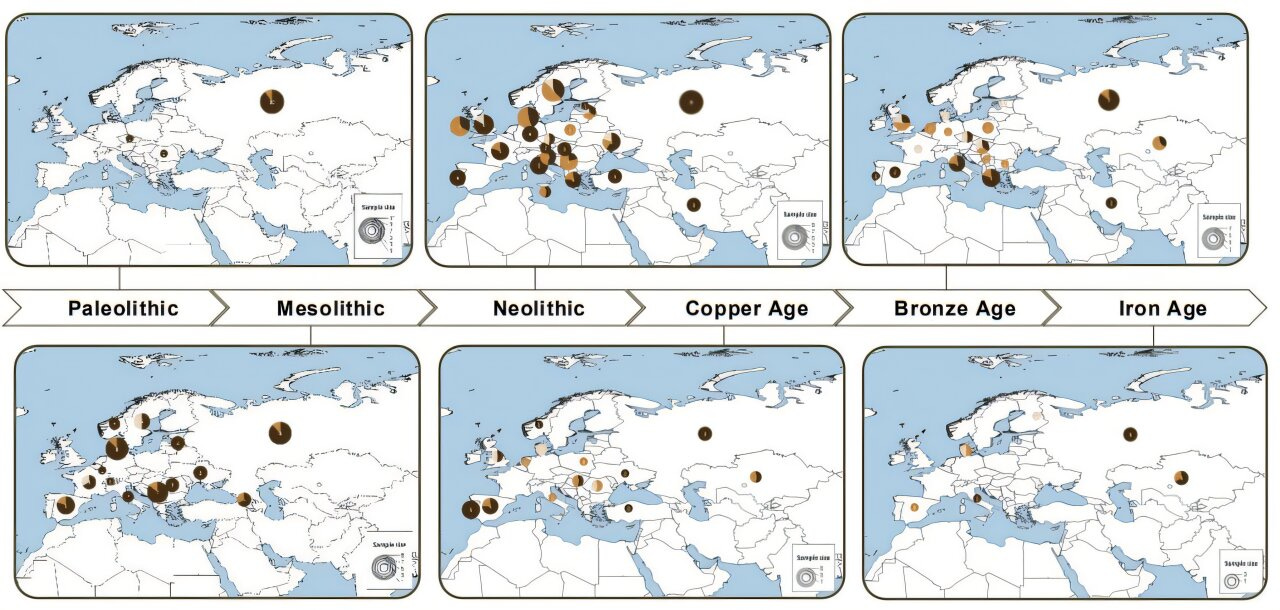

Their findings upend traditional assumptions. Dark pigmentation remained dominant across Europe for much longer than previously thought. Even well into the Copper and Iron Ages—thousands of years after farming spread from Anatolia—half of the sampled individuals still had dark or intermediate skin tones.

“The shift towards lighter pigmentations turned out to be all but linear in time and place, and slower than expected, with half of the individuals showing dark or intermediate skin colors well into the Copper and Iron Ages,” the study notes.

This contradicts earlier hypotheses that light skin became widespread in Europe soon after humans arrived from Africa. Instead, the researchers found that the first light-skinned individuals did not appear until the Mesolithic period (~12,000 years ago), and even then, they were rare. The shift to predominantly lighter skin did not take hold until the Bronze and Iron Ages.

One of the most unexpected findings concerns eye color. The study found that while skin lightened slowly, light eye color—especially blue—experienced a spike in frequency during the Mesolithic period, only to decline again in the Neolithic and re-emerge later.

“This spike in light eye pigmentation appears to be specific to the Mesolithic period. It suggests that, for a brief interval in human prehistory, there was a higher occurrence of the light eye trait compared to both earlier (Paleolithic) and later (Neolithic and Bronze Age) periods.”

Why did blue eyes become more common in the Mesolithic and then decline? The researchers speculate that it could be due to genetic drift, localized selection, or social factors that temporarily favored individuals with this trait.

The transition from hunting and gathering to farming reshaped the genetic makeup of Europe in many ways, and pigmentation was no exception. The study found that the major shift toward lighter pigmentation coincided with the arrival of Neolithic farmers from Anatolia (~8,000–4,000 years ago). These newcomers carried genes for lighter skin, and their migration triggered a transformation in European pigmentation.

However, the study cautions against viewing this as a simple replacement of dark-skinned hunter-gatherers with light-skinned farmers. Instead, it suggests that the change was gradual and shaped by complex interactions between migration, gene flow, and adaptation.

“Pigmentation changes appear to have been driven primarily by migration and gene flow rather than a linear pattern of selection,” the authors write. “The spread of Neolithic farming populations played a key role in shifting pigmentation traits across Europe.”

Surprisingly, even as late as the Iron Age (~3,000 to 1,700 years ago), darker pigmentation was still common in Southern Europe, Russia, and parts of Central Asia. This suggests that light skin was never an evolutionary necessity but rather one of many possible adaptations shaped by cultural and environmental factors.

To understand these changes, the researchers looked at specific genetic variants associated with pigmentation. They confirmed that two well-known genes—SLC24A5 and TYR—played a key role in the emergence of light skin. The SLC24A5 variant, in particular, is found at nearly 100% frequency in modern Europeans but was almost absent in the earliest samples.

Other genes, such as OCA2, influenced eye color, while MC1R and HERC2 contributed to variations in hair color. Interestingly, the researchers also found evidence of adaptive gene flow, meaning that some pigmentation traits may have been introduced through interbreeding with different populations rather than through direct natural selection.

This study adds to a growing body of research showing that human evolution is not a straight path but a complex web of interactions. The authors emphasize that pigmentation traits do not follow a simple north-to-south gradient; instead, they vary based on migration patterns, population mixing, and historical contingency.

“We do not think that the changes described in this paper can be regarded as the effects of a wave of migration proceeding at a regular pace,” the researchers write. “Rather, what we think we are observing is a process in which, above and beyond the major Neolithic demic diffusion over much of Western Eurasia, localized processes of migration and admixture, or lack thereof, played a significant role.”A Complex, Ongoing Story

The history of European pigmentation is far more intricate than previously thought. Rather than a straightforward adaptation to UV exposure, it is a story of migration, gene flow, and cultural shifts. Dark pigmentation persisted much longer than expected, light eye color fluctuated in unexpected ways, and genetic changes occurred in a patchwork pattern rather than a smooth transition.

This research challenges conventional wisdom and opens up new avenues for studying human adaptation. It suggests that many of our assumptions about how and why humans evolved certain traits need re-examining. If nothing else, it reminds us that the past was not a monochrome progression toward modernity, but a kaleidoscope of changing traits shaped by history, environment, and chance.

-

Jablonski, N.G., & Chaplin, G. (2000). The evolution of human skin coloration. Journal of Human Evolution, 39(1), 57–106. DOI: 10.1006/jhev.2000.0403

-

Fu, Q., et al. (2014). Genome sequence of a 45,000-year-old modern human from western Siberia. Nature, 514, 445–449. DOI: 10.1038/nature13810

-

Olalde, I., et al. (2018). The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe. Nature, 555, 190–196. DOI: 10.1038/nature25738

-

Sikora, M., et al. (2019). The population history of northeastern Siberia since the Pleistocene. Nature, 570, 182–188. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-019-1279-z

-

Lin, M., et al. (2018). Rapid evolution of a skin-lightening allele in southern African KhoeSan. PNAS, 115(52), 13324–13329. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1801948115