Summer has begun, and hurricane season is in full swing. As

we keep a wary eye on the storms developing over the Atlantic, we continue to

look back 50 years ago as tropical storm Agnes made land fall over Pennsylvania.

As discussed in prior posts in our Agnes series, destruction of property and

lives was intense with tropical storm Agnes in Pennsylvania, leaving homes and

businesses in disrepair. Agnes imposed tremendous stress on the federal budget

with the passage of the Agnes Recovery Act which allocated nearly two billion

dollars for the relief effort to Pennsylvania alone. This led to changes in

flood disaster protection measures and the creation of Federal Emergency

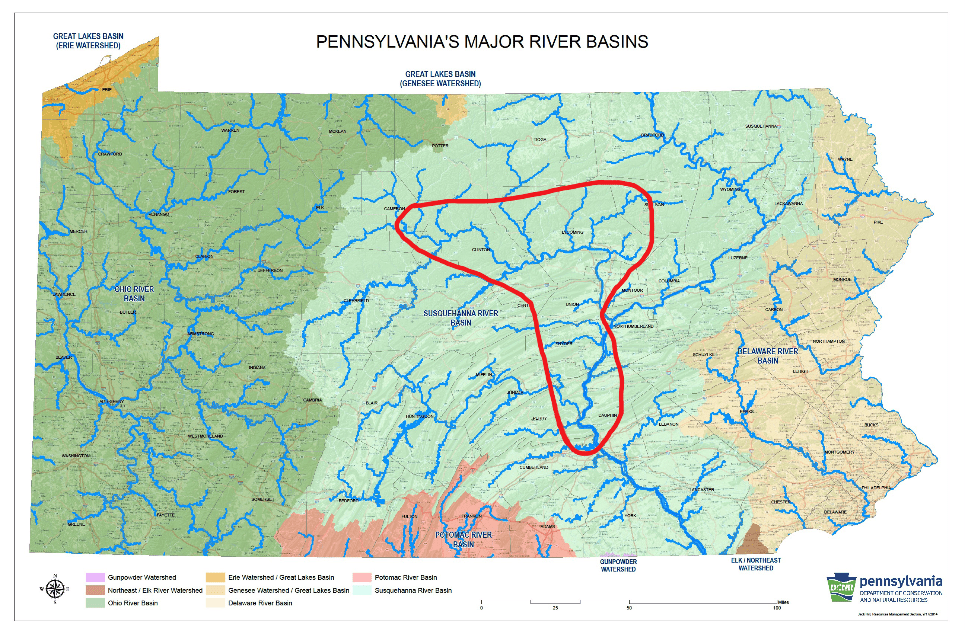

Management Agency (FEMA) (Grumbine 2017). Today we are looking at the results

of Agnes’ fury in the middle section of the Susquehanna River Valley.

June 25, 1972, just two days after the flooded Susquehanna

River crested at 34.1 feet in Williamsport, Pennsylvania an industrious doctoral

archaeology student set out to survey the region. William H. Turnbaugh, a driven

Ph.D. student, watched as the smaller tributaries to the Susquehanna subsided

and drained quickly into the river due to the steeply pitched watershed, not

allowing the river to recede (Turnbaugh 1977). Attributed to the 1955 levee

system built in Williamsport and South Williamsport these cities managed to

escape much of the extensive damage towns and cities further down and up the

river sustained. Deserted towns full of muddy homes, shops, and churches stood as

waters receded and those who fled the surging waters could return (Turnbaugh

1977). Roads were impassable, debris from homes and businesses strewn

everywhere, and farms fields and crops were destroyed.

Once the waters began to recede, Turnbaugh quickly realized

the most visible result of the flooding on archaeological sites was erosion. After

extensive survey throughout Lycoming County, three main types of erosion were

identified as affecting numerous archaeological sites. The first form of

erosion Turnbaugh identified is channel erosion, this is where small streams

would cut across areas to create shortcuts around their natural loops creating

channels through the soil. Sites that Turnbaugh identified as having been

channel eroded include Precontact sites 36Ly11, 36Ly45, 36Ly99 and 36Ly146, all

of which were nearly destroyed by channel erosion (Turnbaugh 1977).

The Late Woodland site (450- 1,100 years ago) 36Ly146 had a

channel running about 500 feet through it with depth up to three feet deep and a

large portion had been washed away. Due to the flood damage and large amounts

of deposited sand and stone very little was found on this site. A few Clemson

Island pottery sherds, believed to be from a single pot, were the main

archeological find at this site after the flooding (Turnbaugh 1972c).

|

| Pottery sherds found at 36Ly146. Image from the collections of The State Museum of Pennsylvania. |

The second type of erosion Turnbaugh identified is pothole erosion,

this is where potholes are created in the ground from eddy currents burrowing. The

site most significantly affected by this form of erosion the multi-component Precontact

site 36Ly74 (450- 10,000 years ago), where a 75 ft x 50ft x 5ft deep pothole

was created (Turnbaugh 1977). Artifacts recovered from this site during the

1972 survey included projectile points, net weights, and a trade bead.

|

|

A netsinker, trade bead and a bifurcate |

The third form of erosion identified by Turnbaugh is sheet

erosion, this is where soils are evenly eroded across a large area. A few of

the sites affected by this form of erosion include the Archaic (11500-4850BP),

Woodland (450-

2,950 years ago), and historic sites 36Ly83 and 36Ly86. The Cliffside

site, 36Ly86 (450- 10,000 years ago), had 90% of the site exposed by the flood,

allowing for numerous precontact artifacts such as stone tools and projectile

points to be found during a surface collection (Turnbaugh 1977). William

Turnbaugh recorded and updated numerous sites in north-central Pennsylvania

following the Agnes flooding, but this was just the beginning, as a larger

survey sponsored by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission continued

this work later in the year (Smith 1977).

|

|

Artifacts recovered from the Cliffside site, 36Ly86. |

The narrow valleys upriver from Williamsport on the West

Branch of the Susquehanna also caused extensive flooding. Sinnemahoning Creek

crested at 19.5 feet, flooding this region, and flowing downstream into the

Susquehanna. This and other creeks and streams in this narrow valley caused the

waters to surge into the river at pinch points flooding the areas that the

streams and creeks led to while also causing waters to rise further down river.

In Renovo, Pennsylvania the water rose and crested at 26.6 feet and in Lock

Haven, Pennsylvania, the water crested at 31.3 feet leading to significant

flooding in both areas (National Weather Service 2017). With widespread flooding in this region,

erosion occurred leading to additional archaeological finds. Included in these

finds are the Martin Whitcomb site (36Cm2), 36Cn49, and the Ramm site (36Cn44).

The Martin Whitcomb site, 36Cm2 spans from the Archaic

through the Woodland (450- 10,000 years ago). After the flooding from Agnes

receded artifacts such as projectile points, netsinkers and other stone tools

were found.

|

|

Stone tools and projectile points |

The Ramm site, 36Cn44 is a Late Woodland site (450- 1100

years ago). Flooding from Agnes led to deep grooves along the rows of planted

crops up to several inches deep. Numerous

artifacts were found after the water receded including Clemson Island pottery

sherds, triangular and other points (Turnbaugh 1972a).

|

|

Artifacts recovered from the Ramm |

The Archaic through Transitional (11500-2800BP) site, 36Cn49,

near Lock Haven, Pennsylvania also incurred extensive erosion due to Agnes. This

site produced projectile points, steatite artifacts, netsinkers and other stone

tools (Turnbaugh 1972b).

|

|

Artifacts recovered from 36Cn49. Image |

Down river from Williamsport, flooding was extensive as

smaller tributaries surged from their banks and inundated the towns, cities,

and the river. Lewisburg, Harrisburg, and numerous towns between were

overwhelmed with flood waters. As in Lycoming County, Northumberland, Union,

and Dauphin County archaeological sites were discovered and further explored

after the waters receded. Landowners, archaeologists, and amateurs worked

together to record and collect on sites. Some of the additional sites found

during the year following Agnes include Pre-contact sites 36Nb6, 36Nb8, 36Nb10,

36Nb61, 36Un10, and 36Da30. The Berrier Island site, 36Da30 (450- 2,950

years ago), was severely eroded by Agnes at the northern tip and western

edge of the island, with approximately 75 feet of the western edge washed away

(Douts 1976).

|

| Flooding of the Governor’s mansion in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania due to Tropical Storm Agnes. Image from Pennsylvania State Archives. |

Along with

sites found directly due to flooding and erosion, additional sites were

uncovered or updated in the process of flood mitigations. One of these sites

includes the Bull Run site, 36Ly119 (450- 10,000 years ago), in Loyalsock

Township found during an archaeological survey for the proposed project to

utilize the Williamsport Beltway roadbed to double as a levee (North Atlantic

Division Corps of Engineers, 1989). After extensive excavations at the

Bull Run site, it was found that a fortified village was located there. Due to

plowing activities and erosion, all occupation levels from Early Archaic to

Late Woodland (450- 10,000 years ago) were in the top 10-12 inches of soil,

indicating that only the bottoms of features remained intact (Bressler 1978). The

few artifacts found on the site represent small bands of people moving through

the area until the Shenk’s Ferry village was erected. Features in the Shenk’s

Ferry Village that were discovered included a stockade and trench, pits, hearths,

and post molds indicating the location of houses. One feature that is usually

indicative of Shenk’s Ferry villages that was not present, are keyhole

structures. This is thought to be the result of the missing topsoil from

erosion and plowing (Bressler 1978).

|

|

Artifacts recovered from the Bull Run Site, |

Another site

that was uncovered due to post flooding mitigations is the West Water Street

site, 36Cn175 (200- 16,000 years ago). This site in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, is

located upstream from the confluence of the West Branch of the Susquehanna and

Bald Eagle Creek causing this area to be prone to flooding (Custer et al.

1994). In 1979 the Army Corps of Engineers established a flood protection plan

around Lock Haven, but it wasn’t until the early 1990’s that the plan began to

be implemented. At the time archaeological work was done along the site the plan

of building a 17.7 foot high, and 100-foot-wide base levee was in place (Custer

et al. 1994).

|

| Lock Haven Levee and William Clinger Riverwalk in 2014. |

In the process

of preparing for the new levee to be built archaeological surveys were

performed, which is how the West Water Street site (36Cn0175) was found. Additional

excavations were conducted on the site, resulting in the discovery of artifacts

and features spanning from the Paleoindian period (10,000- 16,000 years ago)

through the Contact period (about 300-450 years ago). Features such as house

patterns, post molds, a stockade, hearths, and storage pits were all found on

the site. Numerous forms of projectile points and pottery, clay pipe fragments

and stone tools, spanning the long period of time this site had been in use,

were all recovered.

|

|

Pottery recovered from the Clemson Island (450- 1100 years ago) |

Flooding is a continual issue for Pennsylvania and erosion continues

to play a serious role in the loss of archaeological resources. Thanks to the landowners,

amateur archaeologists, and professional archaeologists alike, our cultural

heritage is being recorded and preserved. Numerous sites, beyond what are

listed here, have been recorded thanks to these dedicated individuals. Please

help us continue to preserve our past for the future by contacting your StateHistoric Preservation Office (SHPO) with any information regarding cultural resources and their locations.

Our series on Agnes will continue over the coming weeks as

we move across the Commonwealth and into the Lower Susquehanna Valley. If you missed our Learn at Lunch program on

the impact of Agnes on cultural resources, you can watch the recorded program.

References:

Bressler,

James P.

1978 Excavation of the Bull Run Site in

Loyalsock Township, Lycoming County, Pennsylvania. Report submitted to Pennsylvania

Department of Transportation Montoursville, Pennsylvania.

Custer,

Jay F., Scott C. Watson, and Daniel N Bailey

1994 Data Recovery Investigations of

the West Water Street Site 36Cn175 Lock Haven, Clinton County, Pennsylvania.

Prepared for U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Baltimore District. On file at The

State Museum of Pennsylvania, Section of Archaeology.

Douts, C.

1976

36Da30: Berrier Island Pennsylvania Archaeological Site Survey Form. PA-Share, https://share.phmc.pa.gov/pashare.

Grumbine,

Frank

2017 Inundation of the Heartland Tropical Storm

Agnes and the Landscape of the Susquehanna Valley. Electronic document, https://pa-history.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Grumbine-Pencak-Paper-2017.pdf,

accessed June 3, 2022.

National

Weather Service

2017 Hurricane Agnes: The 45th

Anniversary. Electronic document, https://www.weather.gov/ctp/Agnes, accessed

June 23, 2022.

North Atlantic Division Corps of Engineers,

1989 1989 Water Resources Development in Pennsylvania. Report on file at the University of

Virginia Law Library.

Smith, Ira F.

1977 The Susquehanna River Valley Archaeological Survey. Pennsylvania

Archaeology 47(4):27-29.

Turnbaugh, William H.

1972a 36Cn44:

Pennsylvania Archaeological Site Survey Form. PA-Share, https://share.phmc.pa.gov/pashare.

Turnbaugh, William H.

1972b 36Cn49:

Pennsylvania Archaeological Site Survey Form. PA-Share, https://share.phmc.pa.gov/pashare.

Turnbaugh, William H.

1972c 36Ly146:

Pennsylvania Archaeological Site Survey Form. PA-Share, https://share.phmc.pa.gov/pashare.

Turnbaugh,

William H.

1977 Man, Land And Time: The Cultural

Prehistory and Demographic Patterns of North-Central Pennsylvania. The

Lycoming County Historical Society. UNIGRAPHIC, INC., Evansville,

Indiana.

.