I met Jon Marks in 2015, when I enrolled in the Master’s program in anthropology at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. I had just finished a Bachelor’s degree in anthropology and philosophy at East Carolina University, full of ideas but unsure where they might lead.

I was lucky to have been mentored by Linda Wolfe at ECU, a biological anthropologist with sharp instincts and a habit of cutting straight to the point. When I mentioned that I was weighing a few graduate programs, she cut me off mid-sentence and said, “You’re going to UNCC, and you’re going to work with Jon Marks. He knows everyone, and it will make your life easier.” I didn’t know if that meant my work would improve or if I’d just suffer more efficiently, but either way, I was in.

Early in that first semester, I found Jon in his office and asked if he’d be willing to advise my thesis. He didn’t know me well, but he agreed with little coaxing. He suggested I check in with the department’s only primatologist first, just to avoid stepping on toes, but made it clear he was open to working with me if it wouldn’t cause conflict. He didn’t know me yet, and certainly didn’t have to agree, but he took a chance on me.

I began studying free-ranging rhesus macaques in Central Florida, trying to understand how their social behaviors were shaped by life in a swamp in the US. Jon supported the project, but our conversations kept drifting to topics I (and presumably he) found more intellectually stimulating: how science works, what kind of knowledge anthropology produces, and why it matters who gets to ask the questions. By the time I left for a Ph.D. program at the University of Texas at San Antonio, I was no longer just studying primate behavior. I was trying to understand how humans and wildlife—particularly javelinas—live together in messy, contested landscapes, shaped as much by perception and politics as by biology.

Jon was always there when I needed him, but he never hovered. He had a way of making you feel trusted—like you were capable of figuring things out on your own, and he’d be there if you couldn’t. That kind of support built my confidence more than any direct advice ever could. What mattered to him was that I was thinking clearly and asking good questions. When I did need help, he was quick, direct, and thoughtful. No drama, no performance. Just real mentorship, grounded in trust and respect. The message was consistent: do the work, keep perspective, and don’t take yourself too seriously. He was allergic to pretense, but deeply invested in helping his students think better and more ethically.

That trust extended far beyond the classroom. In 2019, when a student opened fire in one of my classes—killing two students and injuring four others—Jon and his wife, Peta (a brilliant anthropologist and an even better person), became an anchor. Jon had been teaching a graduate seminar just across from the shooting and hunkered down with his students as the campus locked down. In the days that followed, my partner and I spent every evening at their house. There wasn’t any plan or script. They just made space. We ate dinner, talked about baseball, sat in silence when that was what I needed. They didn’t push me to process anything or try to make sense of it. They were just there. That quiet, generous steadiness is one of the main reasons I was able to keep going. It wasn’t therapy. It wasn’t avoidance. It was care, offered without conditions, at a time when nothing else made sense.

That kind of care shaped how I came to understand what anthropology could be. Jon reminded me—sometimes explicitly, often just by example—that good anthropologists don’t just know things. They stay curious, ask better questions, and try not to bullshit themselves. That’s still the standard I try to meet.

And that shift didn’t happen all at once. It happened in long office hours, marginal comments on my writing, and the slow realization that anthropology, done well, isn’t about having the right answers. It’s about learning to interrogate the assumptions we too often treat as given. For me, that meant rethinking not just what counted as knowledge, but what it meant to do the work with integrity, clarity, and care.

And then there was baseball. Jon was a Yankees fan, which was unfortunate, and I’m a Red Sox fan, which is correct. We spent years lobbing petty insults at each other about pitching rotations, blown leads, and cursed franchises. He’d message me mid-season just to gloat, lately with “All rise,” in reference to Aaron Judge’s prolific power.

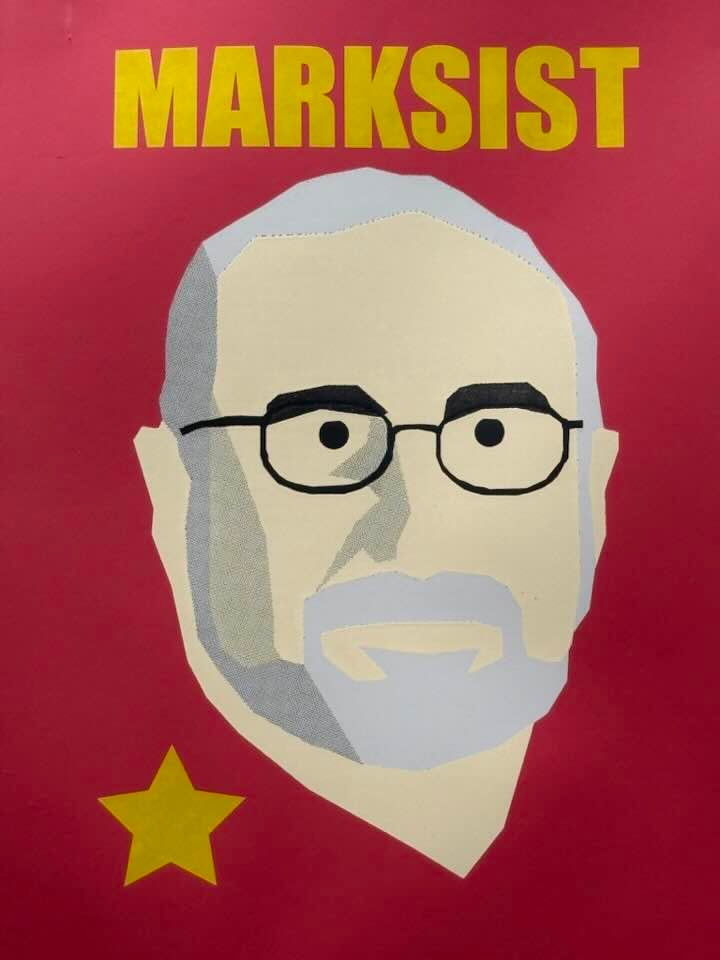

Who Is Jon Marks?

Jon Marks trained as a biological anthropologist, but he never played the part the field expected. He earned his B.A. in Natural Science from Johns Hopkins in 1975, then followed it with an M.S. in Genetics, an M.A. in Anthropology, and a Ph.D. in Anthropology from the University of Arizona—all by 1984. That combination could have led to a conventional academic career tracing gene frequencies and building phylogenetic trees. Instead, Jon turned his deep grounding in genetics into a sharp critique of how science makes claims about human difference.

After postdoctoral work in the genetics department at UC-Davis, he taught at Yale for ten years and Berkeley for three before landing at UNC Charlotte, where he’s spent the bulk of his career. But his impact stretches far beyond campus. Over the last several decades, Jon has become one of the most distinctive voices in anthropology—not just for his critiques of race science and biological determinism, but for the way he invites readers to rethink what science actually does in the world.

He’s known not just for what he argues, but for how he does it: clearly, unapologetically, and often with a dry sense of humor. He didn’t turn his back on science. He insisted that it be better: more historically informed, more ethically aware, and more honest about its blind spots.

Ask anyone who’s read him closely or studied under him, and you’ll hear the same thing: Jon doesn’t hand out answers. He helps you see the assumptions hiding in the questions.

What He Wrote and Why it Matters

Jon’s first book, Human Biodiversity: Genes, Race, and History (1995), came out of a simple but transformative observation: the science of human difference had changed dramatically over the twentieth century, and most people, including many scientists, hadn’t caught up. The book aimed to give readers a way to talk about human variation without resorting to outdated and biologically inaccurate concepts of race. “Human biodiversity,” as Marks defined it, was a corrective. It named the empirical complexity of human difference—its clines, overlaps, and histories, without collapsing those patterns into racial categories.

In the years that followed, online racists appropriated “human biodiversity” as a pseudoscientific banner. Jon called them out directly, writing, “To have provided racists with a scientific-sounding cover for their odious ideas is not something to be particularly proud of, but I can’t take it back. All I can do is disavow it.” He did more than disavow it. He spent his career making it harder to misuse science that way in the first place. Marks responded plainly: “Racists stole it,” he wrote in 2019. The phrase had been coined to name the empirical complexity of human variation in ways that didn’t presume fixed categories or racial typologies. “Human biodiversity,” he explained, “was intended as an alternative way of talking about human variation without the overarching assumption that our species sorts out into fairly discrete, fairly homogeneous races.” That distinction was central to the book. As he later put it, race is real in its consequences, but the reality of race lies in law, discrimination, and political economy and not in our genes.

In What It Means to Be 98% Chimpanzee (2002), Jon took aim at the lazy equations people draw between genes and identity. Just because humans and chimpanzees share a high percentage of DNA doesn’t mean we’re 98% the same in any meaningful way. The book dismantles the idea that genetic similarity can explain what makes us human—or that genes can do the cultural and historical work of explaining behavior, intelligence, or social life. He pushed readers to ask better questions: not how similar are we to other species, but why those comparisons get made, what they’re meant to prove, and who benefits from them. It’s a sharp, funny, and deeply clarifying read. The J. I. Staley Prize committee described it as a book “engaged with issues directly relevant to the future of humanity,” which might sound like an exaggeration until you realize how much damage bad genetics has already done.

Why I Am Not a Scientist (2009) pulled back the curtain on how science operates both as a method and a social institution with its own blind spots, histories, and habits. Jon wasn’t rejecting science. He was asking anthropologists to stop pretending that science speaks for itself. Facts don’t float above culture; they’re produced within it. The book draws on anthropology’s four-field tradition to show how our ways of knowing—whether biological, linguistic, archaeological, or cultural—are always shaped by politics, language, funding, and history. He took seriously the idea that anthropology isn’t just a science of human behavior. It’s also a tool for making science itself more accountable.

In Tales of the Ex-Apes (2015), Jon focused on the stories we tell about human evolution and the authority behind them. The book asks who gets to decide what counts as our evolutionary origin story and what assumptions are built into those narratives. He never questioned whether humans evolved. He questioned why the dominant versions of that story tend to emphasize competition, individualism, and male achievement. Drawing on history, philosophy, and anthropology, he showed how these accounts often reflect cultural values more than fossil evidence. The title challenges the idea that we are simply apes with better tools. It points instead to a species shaped by storytelling, language, and systems of meaning, not just by biology.

In recent years, Jon turned his attention to shorter, more direct books aimed at public debates around science and its misuses. Is Science Racist? (2017) distills decades of critique into a concise and accessible argument: science is not immune to racism simply because it claims objectivity. The book doesn’t indict science as a whole. It asks readers to examine how bias, funding, and institutional history shape what gets studied, how findings are interpreted, and who gets excluded. Why Are There Still Creationists? (2021) takes on science denial more broadly. It unpacks why scientific literacy alone doesn’t resolve cultural resistance and shows how authority in science often depends less on facts than on trust, education, and power. His most recent book, Understanding Human Diversity (2024), brings many of these threads together. It synthesizes his long-standing concerns with race, genetics, knowledge production, and classification, offering a clear guide for how to think about human difference without falling back on outdated categories or deterministic claims.

Beyond his books, Jon has written a litany of articles, ranging from tightly argued academic pieces to public-facing essays that cut through scientific jargon and disciplinary posturing. He has been a visible public intellectual, never content to let anthropological insights stay confined to the classroom or the archive. He participated in public debates like “The Great Ape Trial,” where he brought clarity and wit to questions about species boundaries and personhood. His interviews have appeared in science magazines, blogs, and national media outlets, where he consistently pushed for more honest conversations about race, genetics, and the limits of scientific authority. Whether he was writing for fellow anthropologists or a broader public, his goal was always the same: to get people thinking more clearly about how knowledge is made and why it matters.

Looking Back to Look Ahead

Jon is retiring after this semester. After decades of teaching, writing, mentoring, and prodding anthropology to be sharper and more honest with itself, he’s stepping away from the classroom. That’s hard to picture. His presence has always felt like a kind of gravitational force; he is principled, intellectually sharp, funny, and radically human.

My first experience of Jon was at the 2013 (I think) American Association of Physical Anthropologists—now the American Association of Biological Anthropologists—where, during the business meeting, he stood up and proposed the name change. I later learned this was a recurring event. Every year, he made the case that the name no longer reflected what the field actually studied. Eventually, the association agreed. That moment captured something essential about Jon’s role in anthropology. He didn’t just critique the discipline from the sidelines. He showed up, again and again, to push it toward better language, better ethics, and better self-understanding. He also proposed the creation of the Charles R. Darwin Lifetime Achievement Award, in part to encourage the anthropologist Ashley Montagu to return to the association.

Many of us in anthropology trace our intellectual lineage back to Jon Marks, whether we were his students or not. His influence runs through the questions we ask, the assumptions we challenge, and the standards we hold our discipline to. For those of us who studied with him directly, the impact is obvious. For others, it comes through the pages of his books, his public writing, and the institutional changes he helped bring about. As he steps into retirement, what stands out is the consistency of his commitment, to a holistic understanding of human biology and culture, to calling out scientific dogma, and to holding anthropology accountable for the claims it makes. His work reminds us that science is never just about facts. It’s about the choices we make, the questions we prioritize, and the responsibilities we carry as scholars. That legacy isn’t going anywhere.

Jon’s impact will continue to reverberate through anthropology. His work has reshaped how we think about race, science, and human difference, and he will undoubtedly be remembered as one of the most influential anthropologists in the discipline’s history. For me, that influence is personal. He’s one of the main reasons my career took the path it did, and I’m forever grateful. He doesn’t know this, but I often joke of him as “my withholding father-figure.” That’s not a complaint. It’s how I describe the space he gave me to find my own footing and the unwavering support he’s offered along the way. More than a mentor, colleague, or friend, Jon holds a permanent place in my heart. I admire him deeply as a scholar, and even more as a human.