most

anthropologists surmise that members of early Homo species, rather than the

australopithecines, made those tools. After all, early Homo had a brain

capacity almost one-third larger than that of the australopithecines. But the

fact is that none of the earliest stone tools is clearly associated with early

Homo, so it is impossible as yet to know who made them.

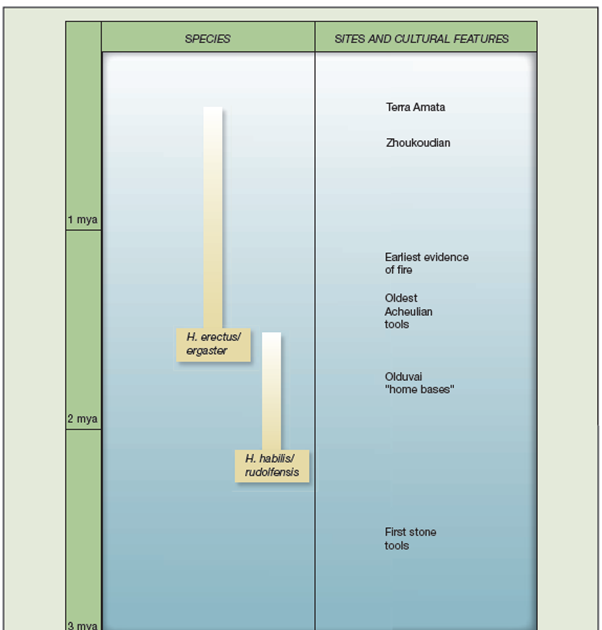

As the figure (on the left) suggests, we can map the

tools usage alongside of the different species of early homo around 2 to 1

Million Years. This clearly reflects the fact that there were existence of

cultural aparatus for adaptation to the environmental challenges.

As we can map between the early homo along

with the stone tool assemblages, we can have roughly the following picture.

Therefore,

as we can see a combination of the biological, especially the fossil evidences along

with the artifact are all we have to imagine what might have been the past

human’s lifeways. Although, it is difficult to

pin-point how, early humans have adapted to their environment and came out of

the challenges, archaeologists and palaeontologists have nevertheless gave us

certain clues. Archaeologists have speculated about the lifestyles of early

hominins from Olduvai and other sites. Some of these speculations come from

analysis of what can be done with the tools, microscopic analysis of wear on

the tools, and examination of the marks the tools make on bones; other

speculations are based on what is found with the tools.

Archaeologists have experimented with what can be done

with Oldowan tools. The flakes appear to be very versatile; they can be used

for slitting the hides of animals, dismembering animals, and whittling wood

into sharp-pointed sticks (wooden spears or digging sticks). The larger stone

tools (choppers and scrapers) can be used to hack off branches or cut and chop

tough animal joints.6 Those who have made and tried to use stone tools for

various purposes are so impressed by the sharpness and versatility of flakes

that they wonder whether most of the core tools were really used as tools. The

cores could mainly be what remained after wanted flakes were struck off.

Archaeologists surmise that many early tools were also made of wood and bone, but

these do not survive in the archaeological record. Present-day populations use

sharppointed digging sticks for extracting roots and tubers from the ground;

stone flakes are very effective for sharpening wood to a very fine point. None

of the early flaked stone tools can plausibly be thought of as weapons. So, if

the toolmaking hominins were hunting or defending themselves with weapons, they

had to have used wooden spears, clubs, or unmodified stones as missiles. Later,

Oldowan tool assemblages also include stones that were flaked and battered into

a rounded shape. The unmodified stones and the shaped stones might have been

lethal projectiles.

There

are many prominent approaches to the understanding of the evolution of human

behavior:

Sociobiology: an approach that uses

principles drawn from the biological sciences to explain human social behavior

and social institutions.

Human behavioral ecology (HBE): a

perspective that focuses on how ecological and social factors affect behavior

through natural selection.

Evolutionary psychology (EP): a

perspective focused on understanding the evolution of psychological mechanisms

resulting in human behavior.

Dual-inheritance theory (DIT): the

perspective that culture is evolutionarily important, that culture evolves in a

Darwinian fashion, and that understanding gene–culture co-evolution is the key

to understanding human behavior.

Contemporary

evolutionary theory has developed new understandings of the complex

relationships between organisms and biological patterns not fully encompassed

by the four genetic evolutionary mechanisms of mutation, natural selection,

genetic drift, and gene flow. Within the framework of the extended evolutionary

synthesis, there is recognition of how extra-genetic inheritances,

developmental biases, and niche construction also contribute to evolutionary

processes, all of which provide the foundations for recognizing the biocultural

patterns that affect human evolution. The approach presented here is known as a

constructivist approach, which emphasizes that a core dynamic of human biology

and culture is processes of construction: the construction of meanings, social

relationships, ecological niches, and developing bodies.

Jablonka

and Lamb point out that explanations of human evolution have traditionally

focused on only one system of inheritance—the genetic system—which relies on

explanations at the level of genes. But human evolution also works in the

epigenetic, behavioral, and symbolic inheritance systems. One such system is

the epigenetic system of inheritance: the biological aspects of bodies that

work in combination with the genes and their protein products, such as the

machinery of the cells, the chemical interactions between cells, and reactions

between types of tissue and organs in the body. The epigenetic system helps the

information in the genes actually get expressed, and therefore it impacts genes

as well as the whole body by altering an individual’s physical traits.

Offspring may inherit those altered traits due to the past experiences of their

parents. In humans, epigenetic inheritance is more difficult to observe because

of our long life spans, genetic diversity, and the fact that we don’t live in

highly controlled environments. Epigenetic inheritance may be taking place,

however, in historical variations in access to food, which can result in health

effects on offspring.

Another

such system is the behavioral system of inheritance: the types of patterned

behaviors that parents and adults pass on to young members of their group by

way of learning and imitation. Consider birds, for example. They must learn

from their parents which foods to eat and which to avoid, since there are no

genes telling them what to eat. In humans, we call these learned and patterned

behaviors norms, customs, and traditions. Cross-cultural variability of human

norms, customs, and traditions demonstrates the behavioral flexibility and

plasticity of humans, something that has long shaped the adaptive possibilities

of our species. We learn a wide variety of behaviors from authority figures and

peers simply by observing and being corrected in everyday life. We also

construct elaborate and formalized social institutions to mediate, manage, and

control the behaviors of group members. These activities consume much of our

energy, thought, worries, and creativity, but none of this activity is located

in any specific genetic sequences. As a result, in humans there is also a

symbolic system of inheritance: the linguistic system through which humans

store and communicate their knowledge and conventional understandings using

symbols. This system of inheritance is intimately tied to the behavioral system

of inheritance. Symbols are rooted in our linguistic abilities. With some

exceptions, all humans are capable of learning a language. This is enabled by a

certain genetic make-up that only other humans share. The actual language we do

learn from our parents and peers then helps shape the way we perceive and interact

with the world around us. Symbols and the meanings people attribute to them are

arbitrary and socially constructed and are not coded in the genes. Another

foundation of the biocultural perspective is the shift in thinking about

evolution that came with the introduction of developmental systems theory

(DST): an approach that combines multiple dimensions and interactants toward

understanding the development of organisms and systems and their evolutionary

impact. DST focuses on the development of biological and behavioral systems

over time rather than on genes as the core of evolutionary processes and

rejects the idea that there is a gene “for” anything. Evolutionary processes

are fundamentally open-ended and complex because they involve the ongoing assembly

of new biological structures interacting with non-biological structures. In

this sense development comes from the growth and interaction of several

distinct systems: genes and cells, muscles and bone, and the brain and nervous

system. All develop over the lifetime of the individual. Thus, evolution is not

a matter of the environment shaping fundamentally passive organisms or

populations, as suggested by natural selection theory, but consists of many

other developmental systems simultaneously changing over time.

Human

evolution is thus characterized by a complex set of interactions among the

various biological systems occurring throughout an individual’s lifetime, all

interacting with factors like human demography, social interactions, cultural

variations, language, and environmental change. These processes make it more

difficult to describe our evolution but do recognize the actual complexity

involved in how human biocultural systems work. A critical aspect of our

biocultural existence involves changing and constructing the world around us. A

niche is the relationship between an organism and its ecology, which affects

how that organism makes a living within a particular environment and leads to

the construction of niches. The scale of niche construction and niche

destruction can occur at the narrow local level or on a global scale and can

change the kinds of natural selection pressures placed on the organisms

involved. Many different types of organisms engage in niche construction.

Much

of what we take as “natural” in a landscape is actually an artifact of human

niche construction and its effects. That human influence over ecosystems is the

defining dynamic of our world today leads a number of scholars to adopt the

term Anthropocene: the geological epoch defined by substantial human influence

over ecosystems. Human reorganization of ecosystems creates conditions for a

co-evolutionary process in which humans, plants, animals, and microorganisms

can mutually shape each other’s evolutionary prospects. Thus, niche construction

creates a kind of “ecological system of inheritance.” These approaches go well

beyond privileging genetic mechanisms as the main or sole force in evolution.

They do fit well with the ways in which some researchers have long seen

selection interacting with environments over the course of evolutionary time

without reducing those processes to natural selection. See “Classic

Contributions: Sewall Wright, Evolution, and Adaptive Landscapes.”

It

would be unreasonable to assume that all of the details previously discussed

are accepted in equal measure. But in terms of meeting the challenge of

constructing a holistic biocultural perspective, which takes culture and

biology equally seriously, these positions provide the basis for a productively

complicated understanding of human evolution. The constructivist approach

acknowledges that biocultural dynamics are open-ended and involve interactions

between diverse forces and agents.

We

can imagine (if not reconstruct) certain cultural aspects as shaping much of

what we are through foods we eat people we chose to mate. For example, Food taboos are generally part of being

human, which involves imposing arbitrary symbolic divisions upon the natural

world, and feeling somewhat arbitrarily that certain things are food and

certain things are not food, in spite of the fact that both classes of things

may be completely edible. The taboos are learned, not instinctual, because they

change with the times, while still evoking diverse forms of repulsion or

aversion. Not eating other humans is simply the food taboo that is most

fundamental and universal. Most food taboos are more provincial: some peoples

eat pig meat, others don’t; some peoples eat dog meat, others don’t; some

peoples eat insects, or poisonous pufferfish, or Twinkies, or whatever weird

things happen to be in their environment and might be nutritious, tasty, or fun

to eat. This is not a biological universe, contrasting things that are healthy

and filling and digestible against things that aren’t; but a symbolic universe,

contrasting things that are considered proper and acceptable to be eaten

against things that aren’t.

Symbolic

boundaries are fundamental to human thought, but of course they are imaginary.

Those boundaries are crucial to group identity, and they may be cast in terms

of what is considered appropriate self-adornment, or how to communicate

properly – that is to say, the “boundary work” of culture. In this case,

however, the symbolic boundary lies not between those who wear saris and those

who wear blue jeans, or between those who distinguish between the “S” sound and

the “Sh” sound and those who don’t9 – but between those who count as human and

those who don’t. The rule is: Animals eat people, people don’t.

Not

only are there certain foods that you cannot eat, even though they are edible,

but there are also certain people that you cannot marry or have sex with,

because of incest taboo even though

they may be really attractive and may love you. The people who are covered by

the taboo may vary somewhat from place to place. As noted above, your first

cousin may be either a preferred partner or a taboo partner. Your first cousin

may even be both – your mother’s brother’s offspring and your mother’s sister’s

offspring may be considered to be different relations, one a fine mate and the

other incestuous. Non-blood relations may be covered by the same taboos as

blood relations, such as your in-laws. The Bible’s incest prohibitions

specifically cover a man’s stepmother, aunt (i.e., uncle’s wife), and

daughter-in-law, even though they aren’t blood relations. There are several

biological consequences of this form of incest, first, this opens up an avenue

for genetic diversification and prevents inbreeding, second, because one has to

find mate outside of his/her close group, one has to wait for a while which

helps getting human the time needed for become physically and mentally mature,

third, this stops indiscriminate sex and gives avenues for human mothers to

rear their children before they pregnant again.

Emergence

of the non-sexual bond between

opposite-sex siblings, which is special to humans, for it creates a new kind of

social relationship: a lifelong intimate interaction between opposite-sex

individuals that is not sexual. This will be symbolically extendable in three

ways: first, to other family members, and banning sexual relations with them,

once there is a concept of the family; second, to other opposite-sex community

or clan members, accompanying a broader conception of kinship than just the

family, and forming the basis of exogamous marriage rules;23 and third, to

other generations, where the offspring of those same taboo opposite-sex

siblings will be cross-cousins, and may be symbolically special, but in the

directly opposite way, as normative spouses.

Further reading: https://global.oup.com/us/companion.websites/9780199947591/sr/ch9/outline/