This is the Introduction post to our new SEEKCommons series. The posts in this series are forthcoming, and will be linked here in this Introduction as they are published over the next several months.

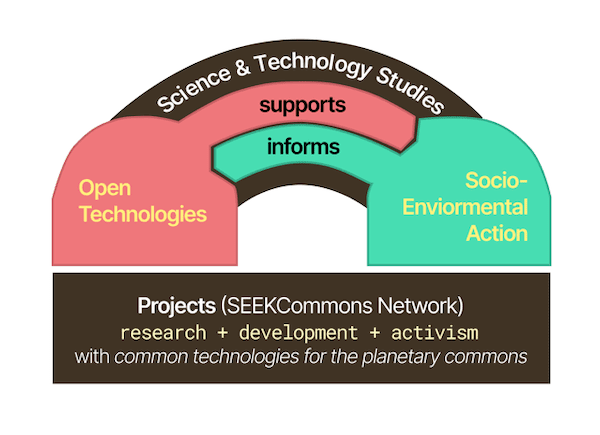

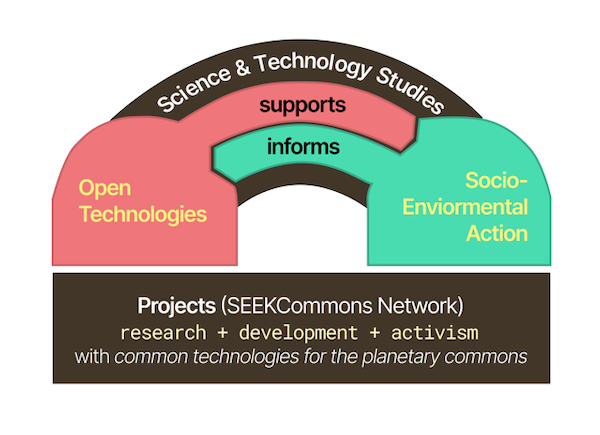

What does the “common(s)” mean for the present and future of science and technology? Are there novel dynamics at play in how knowledge infrastructures are being built, controlled, and contested today? It is with the goal of exploring these interconnected questions that we conceived of the Socio-Environmental Knowledge Commons (SEEKCommons) network—a collective platform where the “common” stands as a political horizon for collaborative social, technical, and environmental work.

SEEKCommons was primarily organized as a response to the mounting urgency we felt around three critical issues. The first overarching issue was the unfolding climate and environmental crisis. While socio-environmental impacts are felt by all, they are experienced in radically uneven ways with varying degrees of vulnerability, disability, and response-ability (Haraway 2016; Vaughn 2022; Taylor 2024). As crises deepen at an accelerated pace, it becomes increasingly clear that addressing them will require fundamental change not only in the political economy of knowledge production, but also in the ways we organize relations of production and reproduction vis-à-vis our relationships with more-than-human worlds. The second issue was perceived in the context of our experiences in Free and Open Source technology circles regarding questions of sustainability, corporate capture, and (gender, ethnic, socioeconomic) discrimination (Dunbar-Hester 2019; Curto-Millet and Corsín Jiménez 2022; Widder et al. 2023). As open technologies became crucial for infrastructuring the technosciences, these systemic problems came to the fore in contemporary debates (Star and Bowker 2002). Another pressing issue, lastly, had to do with the debate on commoning and anti-commoning practices with the increased commercialization of the sciences, but also the collective effort to promote collaborative arrangements among scientists and non-scientists, technologists, and lay experts in so-called community science projects (Brown 1997; Lave 2012; Mirowski 2018; Kimura and Kinchy 2019). As the so-called “Open Science” movement started to gain traction in institutional campaigns, its implications for transdisciplinary social, technical, and environmental work remained unarticulated and underexplored. At this critical juncture, we felt we had the ability to respond collectively with an action research network, since many of us were situated in our scholarly and activist practices at the intersections of these three aforementioned problem spaces.

As a distributed network of researchers, technologists, and environmental activists, we proposed, therefore, to shift the frame from debates about the promises and perils of “openness” to the anthropological question of the “common” as a mode of participatory governance that sits in between markets and states, but also, and most importantly, as a political principle for community-building around common tools and approaches to socio-environmental studies. From this perspective, the work of commoning science and technology is never simply about removing barriers to access, but about transforming the very conditions of knowledge production. It means asking fundamental questions about who participates, who benefits, with what infrastructures, and who gets to shape the research agenda—questions that are often removed from Open Science campaigns. These questions become even more pressing in the context of technoscience’s changing landscape, increasingly shaped by privatization and commercialization (Mirowski 2011). Recentering the common(s) here offers a way to push back against these dynamics, while redirecting our attention to the moral economies of the technosciences. Anthropologists of science, technology, and computing at CASTAC, we suggest, are particularly well-situated to contribute in their ethnographic engagements to the collaborative study of infrastructural, technical, epistemic, and political matters.

What we understand by the “common” is informed by a long tradition of political organizing and empirical research on the ways in which people form collectivities, forge political coalitions, and govern shared resources. This lineage links well-established political and economic anthropology to more recent ethnographic approaches that recognize political histories in technoscientific instruments, infrastructures, and practices—a perspective that has been at the forefront of CASTAC scholarship. To further unpack what we mean by the “common” and its relevance for the critique of technoscience, it is helpful to situate it within the work of Pierre Dardot and Christian Laval (2013) on the topic. They trace the concept back to its Latin and Greek roots to underscore its connections to notions of shared obligation, collective resourcing, and communal ties. The Latin “munus,” they note, originally referred to the duties and benefits associated with public office, which later morphed into “mutuum” in reference to the mutual obligations found in gift-giving, and “communis,” implying community as the act of placing in common. Similarly, the Greek “konein” meant putting something in common, not just in the sense of sharing material resources, but also in the sense of sharing conversations, thoughts, and affects. The derivative “koinonia” captures the qualities of fellowship, intimacy, and solidarity that we associate with community in the fullest sense. Recentering the “common,” in this nuanced sense, Dardot and Laval provide a general framework for cultivating the kinds of associative ties and collective responsibilities that are essential for dealing with the socio-environmental challenges we face at a (common) planetary scale.

In this blog series, we offer a set of posts from SEEKCommons fellows that speak to key areas of research, development, and activism around common technologies for the planetary commons. We start with a piece from José R. Becerra Vera, PhD candidate in Anthropology from Purdue University, whose work is dedicated to the exploration of common tools for the socio-environmental study of air pollution in Inland Empire, California, one of the most polluted regions of the United States and a key logistical hub of big industry. José engages the problem anthropologically by studying air quality reports alongside migrant communities, but also by exploring how common research instruments can be built and shared to engage communities in addressing environmental injustices. He finds support in Fortun’s (2012) ethnographic work on environmental health to highlight how the push for standardized data in the name of scientific openness can override the local, contextual knowledge that is vital for understanding and redressing public health problems.

José’s piece is followed by a think-piece by Vince Tozzi, a Free Software activist and MA student in Science and Technology Studies at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, on the promises and challenges of building common digital infrastructures for creating community archives with the Baobáxia project. For the purposes of integrating data management and stewardship guidelines, Tozzi brings the teachings of Brazil’s black rural communities to the design and implementation of an interface to the popular code versioning tool, Git. Baobáxia was designed around the principle of “eventually connected networks” (Tozzi 2011). Its name is a reference to a “galaxy of Baobab trees,” an evocative symbol of popular Afro-Indigenous resistance. Its connection and importance to action-research on the common should be clear. The software project is much more than a digital project: it is a generative instantiation of the concept of “technological appropriation” with common infrastructural technologies. As one of its main cultural agitators and griots, Antonio Carlos TC, puts it, it is in African cosmology that they ground their understanding of the common. Rather than an investment of collective energy and attention to the dot-com, dot-net, or dot-org approaches, they are primarily engaged instead in building what he calls a dot-us (“ponto-nós”) where we have the possibility of “being” because “we all are.”

Similar to Vince’s concern is a post by Sebastian Zarate, a recent PhD in Anthropology from North Carolina State University, on the “metadata frictions” between indigenous and scientific ontologies (Edwards et al. 2011; Escobar 2016). In his anthropological work, Sebastian studied the archival practices of potato farmers in Peru whose knowledge of potato varieties widely surpasses that of Euro-American scientists. To learn from but also to help communities advance their archival practices, Sebastian has been working with digital technologies that allow for describing and carefully translating across ontologies. For this work, however, Sebastian operates with full attention to what Bezuidenhout et al. (2017) cautioned with respect to standardization efforts in Open Science, since they are often premised on the needs and priorities of resourceful Western institutions, perpetuating existing inequities and exclusions for researchers in research institutions outside the highly privileged pockets of Euro-American universities.

Building on these questions of institutional knowledge is a post by Valerie Berseth, Assistant Professor of Practice at Oregon State University. This piece examines how open science confronts entrenched distrust in Pacific salmon management in Canada. Through ethnographic work with scientists, managers, fishers, and Indigenous groups, Valerie follows both the literal and metaphorical journey of salmon swimming upstream to explore how communities engage with scientific knowledge. Her work shows how distrust is not simply an absence of trust, but rather emerges from histories of marginalization, environmental degradation, and unequal power dynamics. For communities on the frontlines of ecological crisis, she demonstrates how open access to data isn’t enough—trust-building requires addressing the socio-political contexts in which scientific knowledge circulates. Through this case study, Valerie asks us to consider whether open science can truly swim against these powerful currents of distrust and the strategies that might help tackle the deeper roots of skepticism in environmental governance.

Following these questions of trust and community engagement is Erin Robinson’s work on reimagining research infrastructures and data management practices at field stations. Erin, a PhD Candidate in Information Science at the University of Colorado, Boulder, examines FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) principles, exploring how data management frameworks can be transformed to support more ethical fieldwork practices. Her work shows how shifting from FAIR to “fair” principles opens up possibilities for redistributing power to local communities, enabling them to shape research agendas and receive direct benefits from scientific studies. Drawing on her experiences in French Polynesia, Erin examines what she calls “research journeys”—an approach that moves beyond dominant narratives of data collection to consider how knowledge travels and transforms through different cultural and institutional contexts.

Finally, a post by Katie Ulrich, anthropologist and Postdoctoral Fellow at Harvard University and 2023-24 CASTAC Managing Editor, reflects on the creation and online publication of a “sugar library.” During ethnographic fieldwork on sugarcane-based biofuels in Brazil, Katie cataloged over five hundred forms of sugar(cane), capaciously conceived, in order to trace how sugarcane is transformed from a crop with a long and violent history into the basis of sustainable futures. The sugar library contains a wide range of artifacts including physical items, photos, technical documents, reports, knowledge metrics, memories, historical narratives, and even poems and art. Having experimented with ways to publish the sugar library as an online repository for other researchers and as an interactive map to use as a teaching tool, Katie reflects upon the benefits, purposes, and challenges of placing ethnographic data—conventionally difficult to share due to the intimate nature of field notes, for example—in common.

As all of these fellowship projects attest, socio-environmental concerns, from climate change to biodiversity loss to environmental injustice, are complex, multi-scalar, and deeply entangled with social, political, technical, and epistemic dynamics that demand new forms and terms of engagement. Addressing the urgency of these challenges collectively now requires not just shared infrastructural support, but the integration of diverse ways of knowing with distinct moral orientations for the purposes of unlocking what Arturo Escobar (2016) termed “pluriversal” technical, ecological, scientific, and political designs. To this end, we recognize that the tools and practices of Open Science—from Open Data and Open Access to open scientific software and hardware—are far from sufficient in themselves to enable meaningful, ecologically-grounded, and horizontal knowledge-making practices. They can and often are used to sustain new enclosures in the form of rent-collecting cloud computing capital, after all. It is by reframing “openness” as a problem of commoning that we hope to recast the question as a collective project that extrapolates the utilitarian (and latter-day neoliberal) frames of the contemporary technosciences. It is by promoting this reframing toward the common that we hope to help support and be supported by the emergent anthropologies of science, technology, and computing with the SEEKCommons network.

This blog series is offered, thus, as a contribution to the CASTAC community, but also, and more importantly, as a token of appreciation for the work our colleagues have done before us on the technoscientific topics we report here. We hope our CASTAC colleagues enjoy reading this series as much as we enjoyed putting it together.

References

Bezuidenhout, L. M., Leonelli, S., Kelly, A. H., & Rappert, B. (2017). Beyond the digital divide: Towards a situated approach to open data. Science and Public Policy, 44(4), 464–475.

Brown, P. (1997). Popular Epidemiology Revisited. Current Sociology, 45(3), 137–156.

Curto-Millet, D., & Corsín Jiménez, A. (2022). The sustainability of open source commons. European Journal of Information Systems, 0(0), 1–19.

Dardot, P., Laval, C., & Szeman, I. (2019). Common: On revolution in the 21st century (M. MacLellan, Trans.). Bloomsbury Academic.

Dunbar-Hester, C. (2019). Hacking Diversity: The Politics of Inclusion in Open Technology Cultures. Princeton University Press.

Edwards, P. N., Mayernik, M. S., Batcheller, A. L., Bowker, G. C., & Borgman, C. L. (2011). Science friction: Data, metadata, and collaboration. Social Studies of Science, 41(5), 667–690.

Escobar, A. (2016). Sentipensar con la Tierra: Las Luchas Territoriales y la Dimensión Ontológica de las Epistemologías del Sur. Revista de Antropología Iberoamericana, 11(1), 11-32.

Fortun, K. (2012). ETHNOGRAPHY IN LATE INDUSTRIALISM. Cultural Anthropology, 27(3), 446–464.

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

Kimura, A. H., & Kinchy, A. J. (2019). Science by the people: Participation, power, and the politics of environmental knowledge. Rutgers University Press.

Lave, R. (2012). Neoliberalism and the Production of Environmental Knowledge. Environment and Society, 3(1), 19–38.

Mirowski, P. (2011). Science-mart: Privatizing American science. Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard University Press.

Mirowski, P. (2018). The future(s) of open science. Social Studies of Science, 48(2), 171–203.

Star, S. L., & Bowker, G. C. (2002). How to Infrastructure. In L. A. Lievrouw & S. Livingstone, Handbook of New Media: Social Shaping and Consequences of ICTs (pp. 151–162). SAGE Publications, Ltd.

Taylor, S. (2024). Disabled Ecologies: Lessons from a Wounded Desert. Univ of California Press.

Tozzi, V. (2011). Redes federadas eventualmente conectadas. Arquitetura e protótipo para a Rede Mocambos. [Bachelor of Science in Computer Science, UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI FIRENZE, FACOLTÀ DI SCIENZE MATEMATICHE, FISICHE E NATURALI].

Vaughn, S. E. (2022). Engineering Vulnerability: In Pursuit of Climate Adaptation. Duke University Press.

Widder, D. G., West, S., & Whittaker, M. (2023). Open (For Business): Big Tech, Concentrated Power, and the Political Economy of Open AI (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 4543807). Social Science Research Network.