Written by Keith Hart

The classical liberal revolutions were sustained by three ideas: that freedom

and economic progress require increased movement of people, goods and

money in the market; that the political framework most compatible with

this is democracy, putting power in the hands of the people; and that social

progress depends on science, the drive to know objectively how things

work that leads to enlightenment. For over a century now an anti-liberal

tendency has disparaged this great emancipatory movement as a form of

oppression and exploitation in disguise; and, in common with many social

revolutions, it this is partially true. Africa today must escape soon from

varieties of Old Regime that owe a lot to the legacy of slavery, colonialism

and apartheid; but conditions there can no longer be attributed solely to

these ancient causes. It is possible that the example of the classical liberal

revolutions, reinforced by endogenous developments in economy,

technology, religion and the arts, could offer fresh solutions for African

underdevelopment. These would have to be built on the conditions and

energies generated by the urban revolution of the twentieth century.

We all know of course that power is distributed very unequally in our world

and any new liberal movement would soon run up against entrenched

privilege. In fact, world society today resembles quite closely the Old

Regime of agrarian civilization, as in eighteenth century England and

France, with isolated elites enjoying a lifestyle wildly beyond the reach of

masses who have almost nothing. It is not just in post-colonial Africa where

the institutions of agrarian civilization rule today. Since the millennium, the

United States, whose own liberal revolution once overcame the Old Regime

of King George and the East India Company, seemed to have regressed to

presidential despotism in the service of corporations like Haliburton.

It has long been acknowledged that the rise of capitalism in Europe drew

heavily on religion as one of its motors. Max Weber insisted that an

economic revolution of this scope could only take root on the back of a

much broader cultural revolution. If Africa’s informal economy has the

potential to evolve into a more dynamic engine of urban commerce, what

might be the cultural grounds for such a development? As I said, whatever

happens next must build on what has already been put in place. The basis

for Africa’s future economic growth must be the cultural production of its

cities and not rural extraction or the reactionary hope of reproducing

capitalism’s industrial phase. This in turn rests on:

1. The energy of youth and women

2. The religious revival

3. The explosion of the modern arts

4. The communications revolution

5. The new African diaspora linked to sub-national identities

I can only sketch an outline of what is a book-length argument.

- African societies, traditional and modern, have been dominated by older

men. Women have benefited less from their opportunities and are less tied

to their burdens. In many cases they have been quicker to exploit the

commercial freedoms of the neo-liberal international economy. Even when

men and boys have plunged whole countries into civil war, thereby

removing state guarantees from economic life, an informal economy

resting on women’s trade has often kept open basic supply lines. The social

reality of Africa’s cities is a young population without enough to do and a

growing generation gap. The energies of youth must be harnessed more

effectively and the chances of doing so are greater if the focus of economic

development is on something that interests them, like popular culture. - The religious revival in Africa, both Christian and Muslim, is a matter of

immense significance for the forms of economic development. This is in

many cases founded on young people’s rejection of the social models and

political options offered by their parents’ generation. Fundamentalist and

less extreme varieties of religion make a different kind of connection to

world society than that offered by the nation-state, based on the

assumption of American dominance or its opposite. They help to fill the

moral void of contemporary politics and often offer well-tried recipes for

creative economic organization (e.g. the Mourides of Senegal, see below).

Christian churches are usually organized and supported by women, even if

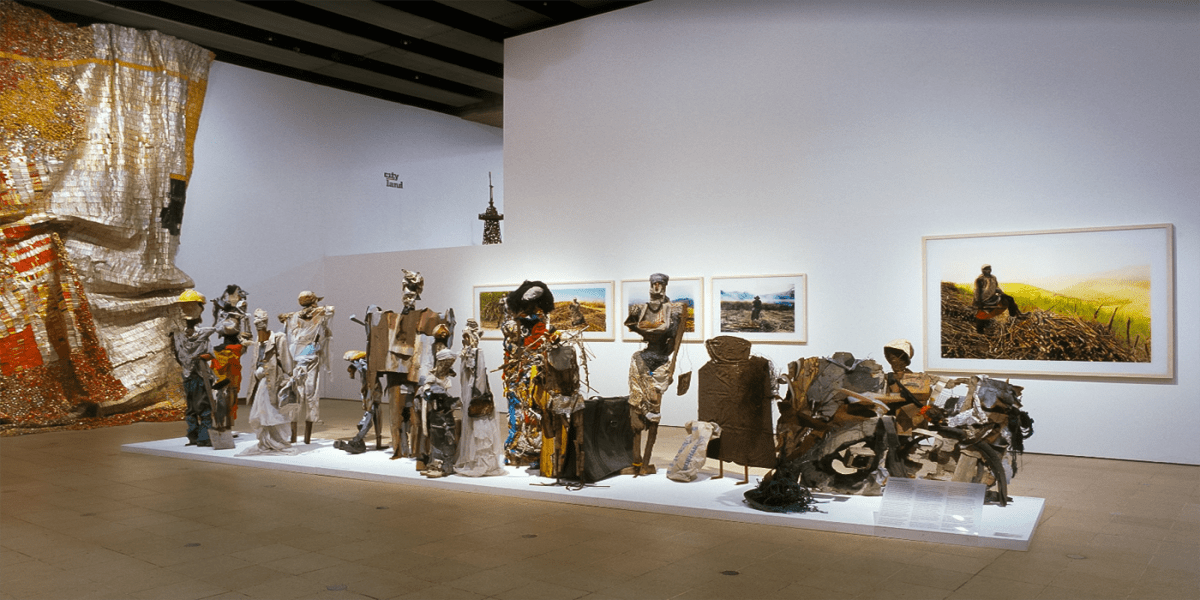

their leadership is often male. - In all the talk of poverty, war and AIDS, the western media rarely report

the extraordinary vitality of the modern arts in post-colonial Africa: novels,

films, music, theatre, painting, sculpture, dance and their applications in

commercial design. There has been an artistic explosion in the

last half century, drawing on traditional sources, but also responding to the

complexity of the contemporary world. One recent example is the ‘Africa

Remix’ exhibition that toured Europe and Japan, a hundred installations

from Johannesburg to Cairo, showing the modernity of contemporary

African art. The African novel, along with comparable regions like India,

leads the world. I have already referred to the creativity of the film industry. - Africa largely missed the first two phases of the machine revolution,

based on the steam engine and electricity; but the third phase, the digital

revolution in communications whose most tangible product is the internet,

the network of networks, offers Africans very different conditions of

participation that they already show signs of taking up avidly. In origin a

means of communication for scientists and the military, the internet is now

primarily a global marketplace with very unusual characteristics. Like the

informal economy, it goes largely unregulated; but this market freedom is

harnessed to the most advanced technologies of our era. The internet has

also generated new conditions for managing networks spanning home and

abroad by radically shortening the time and space dimensions of

communication and exchange at distance. The extraordinarily rapid

adoption of mobile phones has made Africa a crucible for global

innovations, such as the first multi-country network and use of phones for

banking purposes in East Africa. Nor should we neglect the role of

television as a transnational means of widening perceptions of community. - In the last half-century a new African diaspora has emerged, based unlike

that formed by Atlantic slavery on economic migration to America, Europe

and nowadays Asia. These migrants are usually known away from home by

their national identity, but many of them by-pass the national level when

maintaining close relationships with their specific region of origin. They are

often highly educated, with experience of the corporate business world,

while retaining links to relatives living and working in the informal economy

at home. One consequence of neo-liberal reforms has been that

transnational exchange is now much easier than it was, drawing at once on

indigenous knowledge of local conditions and the expertise acquired by

migrants and their families in the West. Remittances from abroad are of

immense importance everywhere, but they are bound to play a major role

in Africa’s economic future.