Foreign Capital to Boost the Development of Africa

Figure 1: Africa Finance Breakfast gathering in Paris in May 2019. Photo by the Author.

“How to earn money and contribute to the development of Africa?” This was the opening line at another gathering of the “Africa Finance Breakfasts” event series on a cloudy morning in early May 2019 at the Paris offices of Jones Day, a major American law firm. The guest speaker that morning was Thierry Deau, the founder and head of one of the biggest sustainable investment funds in France. He was presented in most laudatory terms,

“Mr. Deau’s importance in African investment milieu simply cannot be overstated.”

And the talk itself was just as jubilant:

“With the right type of project management and financial planning, one can both make money and contribute to the development of Africa. Money is not the main obstacle and nor should it be the singular goal. It is true that investors fear Africa—newspapers speak more of security problems in the Sahel than successful start-ups in Kenya. The crux of the matter is good project management—you need to anticipate problems. Even if World Bank and other multilateral institutions have now imposed their rules, you need to be proactive and think of sustainable development. Too many people ignore this.”

For African states the main tool for achieving economic growth was to attract foreign investment.

The whole presentation was fused with a sense of optimism—a brighter future for African countries awaits and great investment projects are already propelling economic growth and improving living standards. Investments simply need to be made the right way and development will ensue. Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, making money or calculations of returns were not explicitly the main object of discussion. Instead, the vagaries and difficulties of project management took centre stage. It was clear to everyone that money was to be made in the process regardless. The underlying assumption, though, was that for African states the main tool for achieving economic growth was to attract foreign investment.

Promising to Cooperate with Foreign Investors

How to make money and contribute to the development of Africa is not only discussed at high finance meetings in European financial centres but also at village gatherings in West Africa.

In December 2013 several dignitaries, formal office holders and representatives of social groups in Nionsomoridou village in Guinea signed on to a letter of engagement promising as the “populations of Nionsomoriodu” to cooperate with Moussa Diabaté and “economic operators” that seek to invest in Guinea and, in particular, in the commune of Nionsomoridou. The letter specified that the engagement to cooperate applies to economic operators “desiring to invest … in the scrupulous respect of procedures, principles, and laws of investment in the Republic of Guinea.”[1] Why such a letter?

We need a bit of the backstory to appreciate where this letter comes from. Nionsomoridou is located next to the known biggest unexploited high quality iron ore reserves in the world, the Simandou mountain chain. These reserves are still not exploited but in the 2000s and 2010s international mining companies were conducting geological exploration in the area. Young people in the villages around the mountain chain were dissatisfied that this activity led to fewer jobs than hoped.

This letter had been presented to the village by Moussa Diabaté, a marabout from the same village. Moussa in particular lead multiple fights against the main mining company Rio Tinto. At one of the key protest events, a former Guinean ambassador to Liberia convinced Moussa to alter course. According to Moussa’s recalling the ambassador would have said:

“Moussa, you care about the community. You should direct projects and not protests. This is how you can really be beneficial to the community.”

Moussa followed his advice and set up a development NGO – Union pour le développement social de Simandou. Representing his NGO, he got to present a project at an investment fair in Liberia. It was a grandiose plan consisting of building several public facilities in the area to foster local development and youth welfare. The event was a success—he found business partners in Nigeria, US and Japan who came to Guinea multiple times to negotiate a deal with the Guinean government and the mining companies that were supposed to provide the funding. Ultimately, the project did not go through and not so much because of any failure on the part of Moussa’s NGO but mostly because mining companies pulled out from Guinea after iron ore prices collapsed in mid-2010s.

Both marabout Moussa Diabaté and investment fund manager Thierry Deau are talking about mobilizing private foreign capital for national economic betterment. What is the political work of drawing foreign capital as an agent of domestic development?

Mode of Regulation

A mode of regulation is paired with an accumulation regime, the two together forming different varieties of capitalism.

Although often used for a more diffuse organizational form of governance (Picciotto 2017), I use the word regulation here in its more generic sense as the totality of rules and ordinary functioning principles of a political ensemble, best expressed in the concept “mode of regulation” developed by the Regulation School of Political Economy (see generally Jessop and Sum 2006). One of the founders of this school, Michel Aglietta, defined a mode of regulation as “a set of mediations which ensure that the distortions created by the accumulation of capital are kept within limits which are compatible with social cohesion within each nation” (Aglietta [1976] 2015).In their approach, a mode of regulation is paired with an accumulation regime,the two together forming different varieties of capitalism (Boyer 2022) such as Fordism, developmental states, regulatory capitalism, corporatism, social vs liberal market economies, embedded liberalism, financial capitalism, petro-states, crony capitalism, tax havens etc. The different national configurations being mutually dependent through international division of labour and global production and wealth networks, they may be more variegations than varieties (Amin 1994; Schwartz 2019; Seabrooke and Wigan 2022).

One thing that many countries especially in Africa, Eastern Europe, Latin America and some parts of Asia have shared in late 20th and early 21st century is a certain fascination if not obsession with attracting foreign direct investment. In both snippets offered earlier, foreign investment is seen as a key tool for achieving domestic economic development and betterment. In this essay, I probe how this orientation to attracting foreign capital could work as a mode of regulation. How is attracting more investment from abroad made to work as a promise for domestic economic betterment?

Foreign Capital for Development

From the 1970s to the 1990s, standard recipes for economic development shifted and countries pulled down all sorts of barriers to cross-border capital movement (Simmons 1999; Abdelal 2007; Chwieroth 2010). In parallel, foreign asset holders’ legal standing was reinforced through investment protection (Perrone 2021; Bonnitcha, Poulsen, and Waibel 2017). In the 1990s, attracting foreign investment seemed the most obvious development recipe (Moran 1998). By the turn of the millennium, the proportions of foreign asset holdings in world economy were again comparable to the peak of high imperialism at the wake of World War I (Schularick 2016). The steady increase in foreign investment stock was even seen as one of the key metrics of globalization. Between the 1980s and 2000s, the world was taken by a foreign investment craze that has still not fully left us although cross-border capital flows have stabilized after the 2008 crisis (Klein 2023).

Building all sorts of infrastructure and large-scale technical systems requires capital investment. As poorer or developing states typically lack the means themselves, it seems natural that development discourse and policy concentrate on sourcing such funds from abroad. Starting in the 1980s, foreign investment, however, came to be seen as windfall. Like manna from heaven, it could emanate from a nondescript nebulous source only reacting to the calling of good projects and attractive destinations.

Regulation […] was about creating attractive business environments that the politicians hoped would bring in cash.

How to attract incoming capital flows became the key policy question in this period and shaped a new mode of regulation. On the most elementary level, states could propose bankable investment projects and propose those to possible investors. On a more general level, though, it was about creating attractive business environments that the politicians hoped would bring in cash. The World Bank even ran an influential Doing Business ranking to measure states’ progress in this domain (Doshi, Kelley, and Simmons 2019). This could mean more benign things like reforming business laws or creating one stop shop solutions for incorporation and getting required approvals and licences. But it also meant signing up for actions that were specifically about curbing domestic political authority: signing international tax and investment treaties, negotiated tax breaks for large investors. The proliferation of special economic zones is perhaps the most staggering example of change to domestic modes of regulation to gain an upper hand in the race for incoming capital under this accumulation regime.

States came to see themselves as vying for foreign investment and started mimicking branding techniques of private businesses (Aronczyk 2013; Pedersen 2010). Whereas in the 1980s, a mere twenty national investment promotion agencies existed in the world, by 2005 close to 120 countries had opened such an agency (Harding and Javorcik 2011). Through advertisements on the pages of Financial Times and The Economist and at events like the Davos World Economic Forum, states now came to promote themselves as investment destinations (Kaur 2020). Even resource rich African states like Angola, Equatorial Guinea or São Tomé and Príncipe all came to peddle wishful narratives of a modern industrial economy beyond extractivist rentier economies (Appel 2017; Schubert 2022; Weszkalnys 2016).

Through legal reforms, special deals and branding campaigns states wooed foreign moneybags and domestic audiences alike with promises of a prosperous future.

Through legal reforms, special deals and branding campaigns states wooed foreign moneybags and domestic audiences alike with promises of a prosperous future. What is this mode of regulation where attracting foreign investment becomes a key tool for economic development?

“Guinea is a virgin country that is waiting nothing but investments”

Let’s return to Guinea where Marabout Moussa had gotten the village of Nionsomoridou to pledge to collaborate with foreign investors to come. Having been the first former French African colony to break independent, it had a tumultuous history with foreign capital. The country had actively sought foreign investment in the 1960s, was somewhat more closed off in the early 1970s and then began seeking inward capital flows again in the late 1970s (Camara 1976; Cournanel 1985). In 1982, the Guinean President Sékou Touré gave an opening speech at the first Guinea Investment Forum organized by Chase Manhattan Bank in New York City. While addressing the crowd as “head of an independent and sovereign nation and as a messenger of the nonaligned movement”, Sékou Touré presented his country as a cornucopia waiting to be seized by foreign capital:

“We are eager to cooperate because what we particularly lack today is capital. God has given us immense natural wealth, but we don’t have the capital or the technology or the know-how to develop it. You will be able to provide us with what we need. … My country offers its considerable resources: minerals, forests, agriculture, energy, and others; the absolute guarantee of all foreign investments; the political stability that’s necessary for the total success of this kind of venture; an open mind; a willingness to engage in a dialogue; and finally, a very high rate of return on investment.” (Touré 1982)

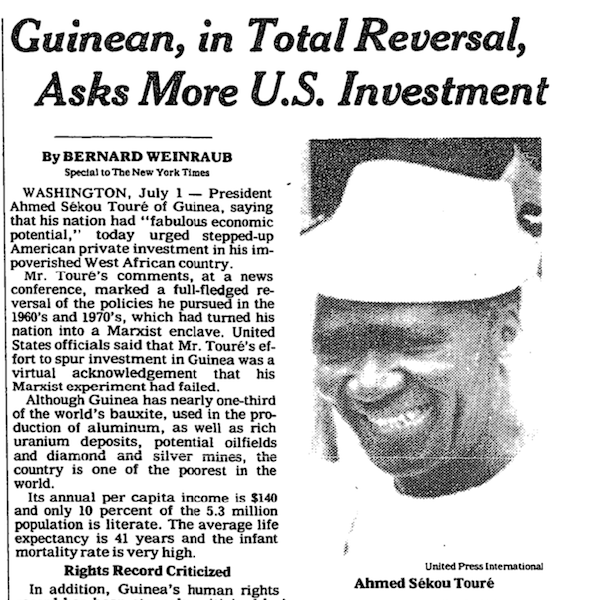

Figure 2: New York Times coverage of the Guinea Investment Forum in Manhattan, NYT 7 July 1982, p. A3. Author’s archives.

One of the most outspoken critics of imperialism […] was now offering his country to be seized by foreign capital like food on a buffet table.

This presentation runs counter to the received understanding of the state as sovereign political authority. Instead, here, Sékou Touré, who had been one of the most outspoken critics of imperialism on the international arena just two decades earlier, was now offering his country to be seized by foreign capital like food on a buffet table.

What may have been new in 1982, was confirmed in the following decades. In a 2002 interview, the then director of the Guinean investment promotion agency put it in even more explicit terms: “Guinea is a virgin country that is waiting nothing but investments” (World INvestment NEws 2002). This proposal eerily recalls European precolonial fantasies of endless riches to be found in yet new frontier territories that can be valorised only through colonizers’ capital and labour investment.

Figure 3: Advertisement for OPIP in Marchés tropicaux, February 14, 2003, p. 321. Author’s archives.

While the talk of states as investment destinations became increasingly common, actually presenting the competitive advantage of any given state remained elusively difficult. Let’s look at a 2003 full-page spread advertisement for Guinea in the French business magazine Marchés tropicaux. It is so full of generic text that it is hard to understand what the actual goal of this advertisement is. It lists all the activities that the Guinean Office for the Promotion of Private Investments is meant to do, even tautologically including a bullet point saying that the goal of the agency is to attract foreign investment. The description seems not to be addressed to any potential investor. Why would they care about all the secondary functions of this government body? The two slogans on the advertisement—“stimulating private investment and effectively participating in the project of sustainable growth and poverty eradication” and “Our mission: lifting Guinea to the status of a development pole that should be hers given her immense potential” are not advertisement slogans for the country but rather declarations about the work of the agency possibly addressed to its financial backers, officials in the World Bank and various development aid agencies.

States as Investment Vehicles

Reconceptualizing states as investment vehicles became a prominent mode of regulation during millennial globalization. Political success here came to hinge on attracting foreign capital and thus political action and the representation of the state become dependent on positioning the state as a recipient of foreign capital that is competing with other states for the same goal. At events like “Africa Finance Breakfast” finance industry compares and assesses states precisely as investment vehicles. On the receiving end, even villages like Nionsomoridou come to be conceptualized as possible investment destinations by aspiring local political leaders.

Centring foreign capital summons a certain performance, a form of raindance-like calling for foreign capital to pour down on the country.

Centring foreign investment as a development tool works as a mode of regulation in two ways. First, it naturalizes an understanding that attracting foreign capital is key for economic betterment. Political discourse is remodelled: states compete to attract the godsend of foreign capital. Secondly, this orientation to foreign capital then calls for practical changes. This has meant considerable political and legal reform: lowering barriers to capital mobility, offering legal safeguards to foreign investors and, more generally, creating a business-friendly regulatory environment. Beyond all the legal reforms, centring foreign capital summons a certain performance, a form of raindance-like calling for foreign capital to pour down on the country. States need to promote and present themselves as attractive investment destinations. Surprisingly, all this has not led to more differentiation but instead more uniformity. Curiously, like in the case of the Guinean investment promotion agency advertisements, these campaigns often fail to show the unique competitive edge of particular countries. Marketing states as investment destinations works more like mimicry, pro forma talk displaying one’s belonging to a global sphere of capital movement and modernity.

Featured image: Pile of 2013 Investment Brochures on top of a cadastre of mining plots in the country. Author’s photo from a presentation by APIP.

Notes

[1] I present the letter with permission and urging from Moussa Diabaté.

References

Abdelal, Rawi. 2007. Capital Rules: The Construction of Global Finance. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Aglietta, Michel. (1976) 2015. A Theory of Capitalist Regulation: The US Experience. Translated by David Fernbach. London: Verso.

Amin, Samir. 1994. ‘À propos de la “régulation”’. In École de la régulation et critique de la raison économique, edited by Farida Sebaï and Carlo Vercellone, 273–98. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Appel, Hannah. 2017. ‘Toward an Ethnography of the National Economy’. Cultural Anthropology 32 (2): 294–322.

Aronczyk, Melissa. 2013. Branding the Nation: The Global Business of National Identity. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

Arrighi, Giovanni. (1994) 2010. The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times. 2nd ed. London: Verso.

Bonnitcha, Jonathan, Lauge N. Skovgaard Poulsen, and Michael Waibel. 2017. The Political Economy of the Investment Treaty Regime. New York: Oxford University Press.

Boyer, Robert. 2022. Political Economy of Capitalisms. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

Camara, Sylvain-Soriba. 1976. ‘Le Parti Démocratique de Guinée et la politique des investissements privés étrangers’. Revue française d’études politiques africaines 11 (123): 52–73.

Chwieroth, Jeffrey M. 2010. Capital Ideas: The IMF and the Rise of Financial Liberalization. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Cournanel, Alain. 1985. ‘Économie Politique de La Guinée (1958-1981)’. In Contradictions of Accumulation in Africa: Studies in Economy and State, edited by Henry Bernstein and Bonnie K. Campbell. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Doshi, Rush, Judith G. Kelley, and Beth A. Simmons. 2019. ‘The Power of Ranking: The Ease of Doing Business Indicator and Global Regulatory Behavior’. International Organization 73 (03): 611–43.

Harding, Torfinn, and Beata S. Javorcik. 2011. ‘Roll Out the Red Carpet and They Will Come: Investment Promotion and Fdi Inflows’. The Economic Journal 121 (557): 1445–76.

Jessop, Bob. 2016. The State: Past, Present, Future. Cambridge, UK Malden, MA: Polity.

Jessop, Bob, and Ngai-Ling Sum. 2006. Beyond the Regulation Approach. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Kaur, Ravinder. 2020. Brand New Nation: Capitalist Dreams and Nationalist Designs in Twenty-First Century India. South Asia in Motion. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Klein, Matthew C. 2023. ‘Financial Fragmentation’. 28 June 2023.

Moran, Theodore H. 1998. Foreign Direct Investment and Development: The New Policy Agenda for Developing Countries and Economies in Transition. Washington, D.C.: Institute for International Economics.

Pedersen, Ove Kaj. 2010. ‘Institutional Competitiveness: How Nations Came to Compete’. In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Institutional Analysis, edited by Glenn Morgan, John L Campbell, Colin Crouch, Ove Kaj Pedersen, and Richard Whitley. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Perrone, Nicolás M. 2021. Investment Treaties and the Legal Imagination: How Foreign Investors Play by Their Own Rules. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Picciotto, Sol. 2017. ‘Regulation: Managing the Antinomies of Economic Vice and Virtue’. Social & Legal Studies 26 (6): 676–99.

Schubert, Jon. 2022. ‘Disrupted Dreams of Development: Neoliberal Efficiency and Crisis in Angola’. Africa 92 (2): 171–90.

Schularick, Moritz. 2016. ‘International Capital Flows’. In The Oxford Handbook of Banking and Financial History, edited by Youssef Cassis, Catherine R. Schenk, and Richard S. Grossman, 0. Oxford University Press.

Schwartz, Herman Mark. 2019. ‘American Hegemony: Intellectual Property Rights, Dollar Centrality, and Infrastructural Power’. Review of International Political Economy 26 (3): 490–519.

Seabrooke, Leonard, and Duncan Wigan, eds. 2022. Global Wealth Chains: Asset Strategies in the World Economy. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Simmons, Beth A. 1999. ‘The Internationalization of Capital’. In Continuity and Change in Contemporary Capitalism, edited by Herbert Kitschelt, 36–69. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Touré, Ahmed Sékou. 1982. ‘What Role for U.S. Capital?’ Africa Report; New York 27 (5): 18–22.

Weszkalnys, Gisa. 2016. ‘A doubtful hope: resource affect in a future oil economy’. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 22 (S1): 127–46.

World INvestment NEws. 2002. ‘How to Invest in Guinea?’, 4 February 2002.

Abstract: In the last decades of the twentieth century, attracting foreign investment became to be seen as one of the most important tools for attaining economic development. States thus came to compete for incoming capital flows. Drawing on classical works in Regulation School, I analyse how the states were reconceptualized as investment vehicles in the hopes that enticing foreign capital will bring about economic betterment. Drawing primarily on the example of Guinea, I show that the focus on attracting foreign investment modifies the mode of regulation in those countries and ultimately alters what is seen as the goal of the state. Not only does international finance compare states as possible investment destinations, but even villages in Guinea create political structures to become attractive in the eyes of foreign capital. Paradoxically, attracting foreign investment leads to less differentiation between states. Instead, advertising, and legal reforms to attract foreign investment often mimic global standards and pedal a generic upbeat rhetoric of development opportunities.