Article begins

Peter sits on a chaise lounge with a clear vessel full of a shake he’s about to drink. He holds it up to show its brownish-red color and thick consistency, plugs his nose, and drinks the shake, emptying the vessel. From offscreen, the viewer can hear the cameraperson, presumably Peter’s girlfriend-donor, say “Wow.”

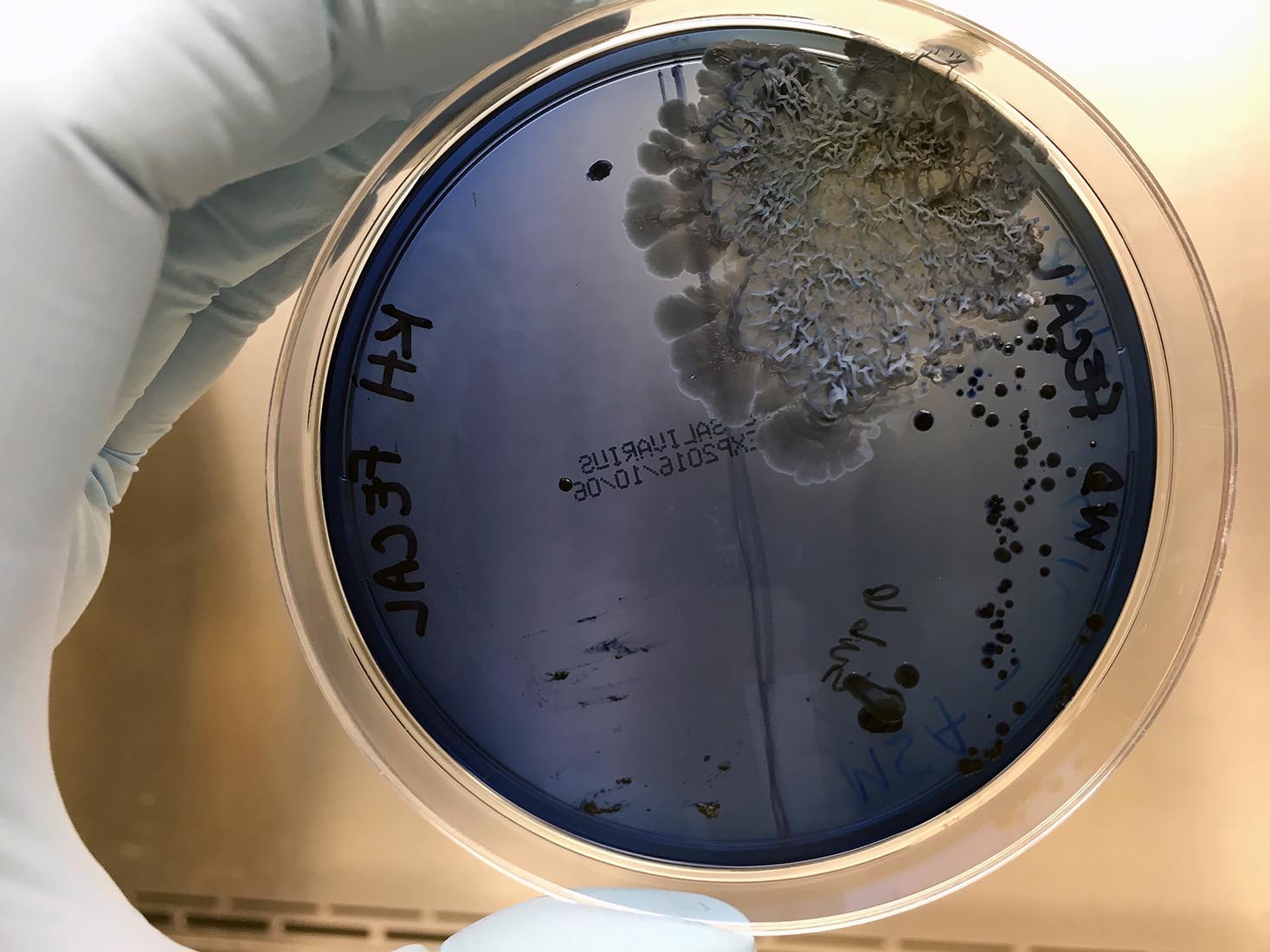

By reading the comments on the video—posted to a gastrointestinal disorder support group on Facebook—one learns that Peter’s shake is made of his healthy girlfriend’s feces, distilled water, and a mix of berries. He explains in his interactions with commentators that his radical approach to fecal microbial transplantation (FMT) is motivated by his understanding that his gut health and his mental health are intimately linked. Fighting depression, Peter has embraced a practice of drinking his excremental shakes and fasting in the hopes that the infusion of microbial agents will displace the microbes that lead to his imbalances of health.

Peter is caring for his microbes and his whole-body health, through a practice of stewardship: he is targeting nonhuman actors with the goal of improving the ecology of his body, which I write about in American Disgust.

As often as I dwell on Peter, I return to the Suskind family and their practice of communicating with their son, Owen, as recounted in Life, Animated.

Diagnosed with nonverbal autism at an early age, Owen consumed Disney media with editorial detail. Playing VHS tapes of Disney films, he would rewind scenes and dialogue repeatedly, to his family’s chagrin. Only later would they realize that Owen was learning to talk through his Disney film consumption. Their first inkling of this is when Owen repeatedly says “juicervose” and his family pieces together that he is echoing the phrase “just your voice” from The Little Mermaid—the cost Ariel pays to be able to walk on land. Initially dismissed by Owen’s psychiatrist as mere echolalia, Ron, his father, is undeterred.

Hiding, but with his puppet-adorned hand visible, Ron engages Owen in conversation as Iago, the villain’s sidekick from Aladdin, which he recounts in their family memoir:

“So, Owen, how ya’ doin’?” I say, doing my best Gilbert Gottfried. “I mean, how does it feel to be you!?”

Through the crease [in Owen’s bedsheet], I can see him turn toward Iago. It’s like he was bumping into an old friend.

“I’m not happy. I don’t have friends. I can’t understand what people say.”

I have not heard this voice, natural and easy, with the traditional rhythm of commonspeech, since he was two.

I’m talking to my son for the first time in five years. Or Iago is.

(Suskind 2014, 55)

The Suskinds find that they can communicate with Owen in an increasingly open manner, once he has been unlocked through the shared media of Disney films. In the early years, their communication involves voice-acting and role-playing—sometimes recreating whole scenes to communicate a message—and eventually it comes to involve a shared understanding of the media that is so vital for Owen.

I came to conceptualize this form of care for Owen as animation, which I write about in Unraveling: Owen is animated into speech through his affection for the Disney films and their characters and his family is animated into their novel communication practices through their affection for Owen.

Both stewardship and animation are kinds of care yet I worry that only describing them as “care” loses too much in its imprecision. It feels like biting the hand that has fed me, but I have increasingly become skeptical of subsuming all of the activities that comprise care under that umbrella; care describes too much, its vagueness has become a liability in advancing the mission of making a more caring society. When we subsume all care activities as “care” we draw attention away from the diversity of practices that need support as caring. Describing the multiplicity of caring activities in their specificity helps to flesh out what people and institutions do to make livable lives and helps to focus on the people, technologies, and policies that make diverse forms of care possible.

It’s time to forget care.

I came to this position because of the debates about Facilitated Communication (FC). FC first became popular in the 1990s, when caregivers for disabled people drew attention to the practice as means to enable nonverbal people to communicate. Carers would support the arm or hand of a communicator, allowing them to type out a message on a keyboard or point to an image on a communication board. FC quickly became subject to public scrutiny and debate, as debunkers demonstrated that it was the carer and not the communicator who was communicating, as the carer moved the communicator’s hand to create a message. These debates were recently resurfaced in Tell Them You Love Me, a Netflix documentary about the abusive relationship between a professor and a disabled person.

But many people use FC and Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) and don’t draw attention to it, for fear that they will be disallowed from its use because of the controversies about it. There is a simple test to prove the individual use of FC and AAC as valid: show the communicator a message or set of images without the carer; show the carer a different message or set of images without the communicator; bring them together and ask them to reproduce the message or set of images. If it matches the carer’s message or set of images, the use of FC or AAC is tainted and might not work for that communicator. To sweep away all uses of FC and AAC as tainted ignores that for some people, these systems of care work.

Drawing attention to the specifics of care practices—like FC and AAC—allows for the development of caring practices, policies, and institutions that support those forms of care and their specificities. When we ignore or avoid those practices, we run the risk of endangering their positive uses and existence altogether.

Feminist ethics and political theories of care and caring institutions have succeeding in shaping scholarly trends in the early twenty-first century, evident in the dominance of care in scholarship across the social sciences and humanities. This attention to care served as a corrective to prior attention to masculinized, public-facing institutions, and was integrated into ethnographic interest in what Michel Trouillot referred to as “the suffering slot,” which offered the opportunity to consider who is involved in the suffering of others, the social contexts of care, and how caring might be done otherwise. Care has been wildly successful as an addition to the social scientific lexicon and it’s critical to recognize this success as a necessary threshold for what should come next.

It is often difficult to do much with “care.” At once, care means everything and nothing: the provision of food and shelter, aid in toileting and daily hygiene, support for everyday activities, systems of solidarity and mutual support, sustainable agricultural practices, bureaucratic processes—even, in some cases, the provision of addictive drugs and violent abuses are cast as forms of care. This work grew out of feminist ethics and political theories of care and added nuance, as ethnography often does, to particularize what care can comprise, its varieties, and limits. That work has been vital, but when its contributions are subsumed under “care,” we lose the opportunity to draw attention to these micro-practices of care, both as life sustaining and theory generating.

Stewardship, animation, and facilitation are examples of “middle theories” of care. They intercede as descriptions of specific, everyday practices that can be generalized toward an umbrella conception of care. Consider these other examples and the middle theories they point toward:

Don Kulick and Jens Rynstrom described the practices associated with supporting disabled people in forging intimate connections, including sex acts, in Swedish and Danish residential facilities. This included the need to help disabled people use contraceptives, position their bodies in comfortable poses, and the creative use of furniture and mobility aids. Kulick and Ryndstrom passingly refer to this collection of practices as “facilitation,” which captures the ends-driven aspect of what care-providers seek to do for their clients.

Elana Buch describes the ways that in-home care-providers smell and taste foods for their elderly clients, whose senses have become impaired with age. By smelling and tasting for their clients, the care-providers seek to make sure that people aren’t inadvertently poisoning themselves by consuming spoiled food. Buch describes this as a form of embodiment, extending the corporeal senses of the clients through their caregivers.

Focus on human-to-human forms of caring cast care as a relational prosthetic, a way that what we can’t do for ourselves can be done by someone else who acts as a surrogate for our limitations of capacity. The agencies of one person are substituted for the agencies of another person, often with institutional support; when this support is failing or unavailable, care becomes a hardship and a scarcity, subject to economistic thinking that can impact caregivers and recipients of care alike. Care-focused scholars rightly demonstrated how impingements on the provision of care led to the limitations of recipients of care and the outcomes of their lives.

Moving into more-than-human contexts—like Peter’s stewardship of his gut microbes—raises questions about the impacts of human agency and shifts the parameters of what care is and does.

Katy Overstreet provides a parallel example to Buch’s, albeit rather than in-home caregivers tasting for their clients, farmers, nutritionists, and veterinarians substitute their sense of taste for that of the cows they care for. Rather than merely substituting their capacities for their bovine charges—one human’s sense of taste substituting for another’s—humans impose their capacity for taste on those they care for, imagining what is good for cows. These acts of substitution also seek to aid bovine gut flora, who, in turn, care for their bovine hosts by digesting food materials that cows couldn’t do without microbial aid. Caring for cow nutrition is also caring for microbial well-being, which enters both into complex, more-than-human chains of relation that support human and nonhuman lives.

Or, as Jose Cañada, Salla Sariola, and Andrea Butcher argue in their attention to microbial impacts on their environments, policies concerned with dangers associated with rising anti-microbial resistance emphasize the concerns of humans and their fears of disease. A more-than-human perspective on policy making as a kind of care would foreground the roles that microbes play in their non-human environments, leading to—potentially—negative effects for humans for the sake of maintaining the broader well-being of other inhabitants of an environment. Facilitating the needs of others might entail threats to those who provision the care, which includes both humans and nonhumans. Having a full accounting of who will confront which harms ensures an awareness of the possible repercussions of an act of care.

In these more-than-human examples, it’s difficult to accept these practices as forms of care analogous to what is enacted in human-to-human contexts. While they might all be forms of “care,” they are so different as to render their similarities less important than their differences.

One critical difference is the power relations inherent in any care relationship. This is routinely at issue in human-to-human care provision, as pastoral relationships mediate recipients’ access to the care they need, from accessibility provisions in classrooms and at work to approvals for medical treatments and prosthetics. The differences between those rendered powerless because of institutionalized and widely accepted forms of ableism, as in Kulick and Ryndstrom’s case, is necessarily different from the foreclosure from enactments of power that microbes and cows experience. Even those putatively in power, as in the case of Owen’s parents, find their access to resources shaped by disbelieving medical professionals who limit Owen’s available support systems, including speech therapy and classroom provisions.

Another element to consider is the symmetry in the relationships between caregivers and recipients; whose needs are being privileged and how? Peter, like the policy makers Cañada, Sariola, and Butcher invoke, privilege human well-being over that of the microbes under scrutiny. The perspective from Peter’s gut is very different than from his human-to-human relations; he privileges his mental health and relations with his human friends and family over the well-being of the microbes in his gut, who will die with the infusion of a novel colony of invaders. Putting Peter’s self-care into that language begs questions about what’s at stake in how we describe care relations and the need for even greater specificity in ethnographic approaches to care.

Middle theories of care allow us to compare practices across contexts. As ways to capture a diverse set of practices and make them portable, middle theories of care provide a means to attend to the minutiae of ethnographic description, which includes both the more-than-human interactions and human statements of intention. In many respects, ethnographers have already been providing this detail but have been subsuming it in attributions of a wide variety of practices to “care.” Emphasizing acts of care in their details and situating them at the forefront of theorizations of care as based in the everyday lives of individuals helps to enrich theories of care and drive support for the kinds of care that people need to live.

Moreover, attention to middle theories of care might treat care as an ethnographic object that remakes our subjectivities as ethnographers and attends to the diverse subjective experiences of people experimenting with what care might be and make possible. In conceptualizing care’s specificities, including how we as ethnographers and others as care’s givers and recipients imagine what they are doing when they enact care, we provide language for approaching what caring practices can and should accomplish.

Stewardship brought this home to me, as I wrestled with how Peter’s consumption of feces-based shakes and calls for attention to “planetary health” articulated the same problem across scales and contexts: environments needed to be managed for the benefit of human health. A key element of both personal and planetary health is microbial thriving, which, in a human body, ensures immune functioning and digestion, and in ecological systems, ensures safe water and productive and nutrient-rich crops. Understanding caring for microbial health as a form of stewardship lends precision to the needs and practices that Peter and the planet need.

Peter needs access to health-promoting feces, the screening technologies to ensure his safety, distilled water, and an empty glass; he needs the support of health care providers who accept his treatment choices and can monitor his well-being.

As a planetary population, we need access to safe food and water that are sustainably produced to ensure the long-term well-being of us and our succeeding generations. We need technologies that monitor and support planetary well-being and policymakers and politicians that advocate for forms of regulation that protect us and the planet.

Conceptualizing Peter’s needs and the needs of a planet and planetary population as expressions of stewardship helps to draw attention to the points of convergence between them; such attention focuses care on the access to resources and technologies, training of experts, implementation of policy, and publicly accessible education that make microbial thriving possible.

Embracing stewardship, facilitation, and animation as caring experiences and ways of conceptualizing human-human, human-nonhuman, and human-environment interactions has changed the ways that I perceive bodies. Rather than conceive of them as isolated objects that other bodies and environments act on, bodies are landscapes. As landscapes, they have other landscapes laminated onto and into them: microbial colonies, chemicals and nutrients, radiation and particulate matter, institutional obligations and social norms of behavior, policies and their effects, structural forms of discrimination. Providing care for an individual entails more than steady access to resources. It demands attention to the many landscapes that comprise a body and the ways they interact and to what effect.

Attention to care and the need to make a more caring world was a vital impulse of the first wave of care scholars. The avoidance of care, as an object of study and as a social good, is always an ethical problem. Forgetting “care” is a way to reinvigorate the ethical mission of attending to care: how can we, under the banner of care, forward support for the kinds of care that individuals need and desire, to give and to receive? How can abandoning “care” produce a humility in our descriptions of more-than-human relations and interdependencies as a means of making more just and sustainable worlds? How can attention to other ways of living in and describing the world provide more nuanced ways of caring for human and nonhuman individuals, communities, and whole ecologies?

Advancing the ethics of care depends on accepting our successes as scholars, activists, caregivers and recipients of care, and moving forward to ensure that humans and nonhumans have the infrastructures, resources, and attention they need to have livable lives. Achieving these goals depends on articulating forms of care that work across scales, that denaturalize bodies and environments as isolated from each other, that find commonalities in need, and that unify concentration on the provision of resources and access. The neoliberal logic of care individuates care and sets individuals and constituencies against each other for meager resources; finding consonance across needs depends on adhering to the intricacies of care that allow solidarities to be built across bodies, communities, and environments.