In 1949, a hominin mandible was unearthed from the Swartkrans cave system in South Africa. Dubbed SK 15, the fossil spent the next 75 years being shuffled between taxonomic categories like an unsolved puzzle. Originally identified as Telanthropus capensis, it was later reassigned to Homo ergaster, occasionally flirted with an Australopithecus classification, and was even compared to Homo naledi. But none of these labels seemed to fit. Now, thanks to cutting-edge imaging techniques and geometric morphometrics, researchers have finally settled on a new identity for SK 15: Paranthropus capensis, a previously unknown member of the Paranthropus genus.

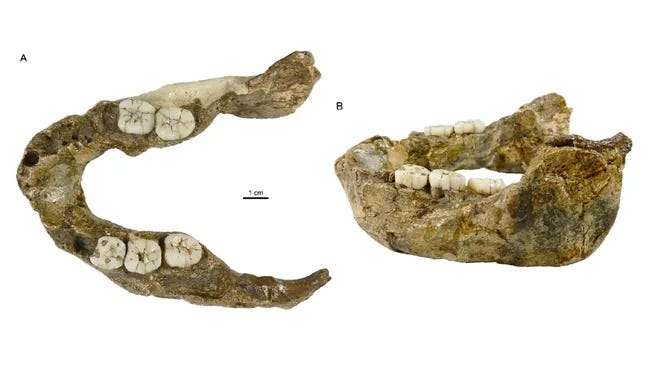

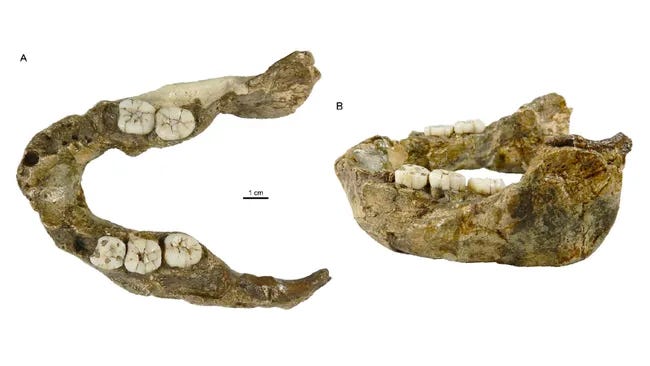

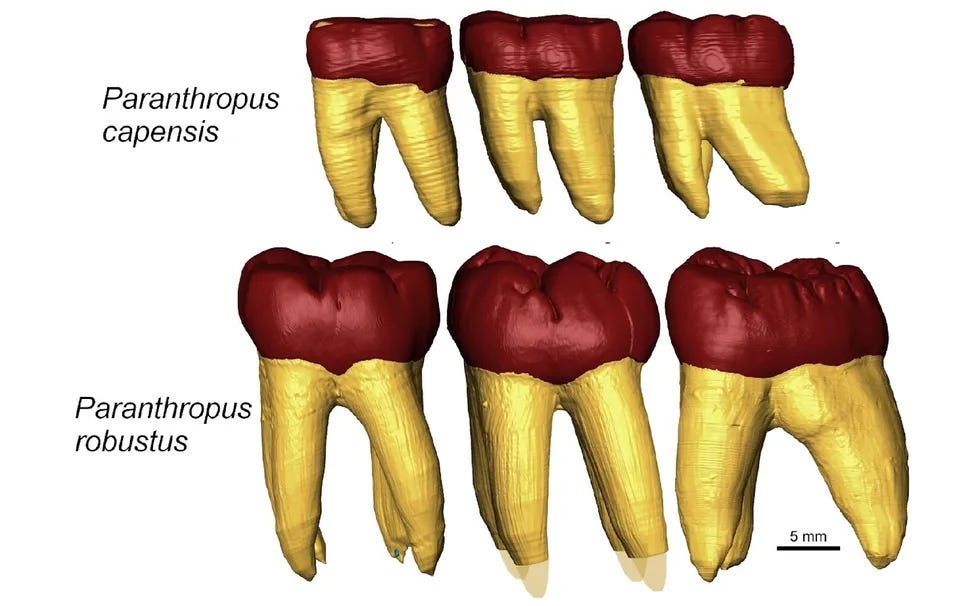

The study, published in the Journal of Human Evolution, analyzed SK 15’s bone and tooth structure using X-ray microtomography, a method that allows researchers to peer inside fossils at microscopic levels. The findings were striking. SK 15’s mandible was far too robust to be an early Homo, yet too gracile to belong to Paranthropus robustus, the well-known South African species. The molars were elongated, but smaller than those of P. robustus or P. boisei, and the overall shape of the jaw hinted at an evolutionary offshoot.

The conclusion? SK 15 belonged to a previously unrecognized species of Paranthropus. The research team has proposed reviving its original species name, capensis, but this time within the Paranthropus genus rather than Telanthropus, an obsolete category.

“Altogether, the results show that SK 15 unambiguously falls outside the variation of H. erectus/H. ergaster and that it is most compatible with the morphology of Paranthropus, albeit showing smaller dimensions and an absence of some dental morphological features,” the researchers explain in the study.

The discovery of P. capensis suggests that at least two Paranthropus species coexisted in southern Africa around 1.4 million years ago. This raises intriguing questions about how these hominins divided their ecological niches and what role they played in the broader hominin landscape.

If Paranthropus species are famous for anything, it’s their powerful jaws and enormous molars, earning them the nickname “Nutcracker Man.” They were the tank-like herbivores of the hominin world, built to grind down tough plant matter. But P. capensis seems to break the mold. Its jaw, while still robust, is notably smaller and lacks some of the exaggerated chewing adaptations of its relatives.

“*They probably had different ecological niches,” lead author Clément Zanolli explains. “P. robustus likely had a highly specialized diet, as suggested by the massive jaw and teeth, while P. capensis, which displays smaller teeth and a less robust mandible, might have had a more varied diet and potentially exploited different food resources.“

This suggests P. capensis may have been more adaptable than its larger-jawed cousins. While P. robustus was fine-tuned for chewing fibrous plants, P. capensis may have had a more flexible diet, possibly including softer plant foods, fruits, or even small animals.

Southern Africa during the Early Pleistocene was a lively place, evolutionarily speaking. P. capensis wasn’t the only hominin on the scene. The region also hosted Homo ergaster, the species that would eventually give rise to Homo erectus, and Paranthropus robustus, its more famous cousin. The coexistence of these species presents a tantalizing mystery:

The answers remain elusive, but the discovery of P. capensis adds yet another layer of complexity to the story of early human evolution.

The classification of Paranthropus has always been a subject of debate, and P. capensis complicates the picture further. It is more gracile than P. robustus and P. boisei, yet still distinct from Australopithecus. Its discovery forces researchers to reconsider the evolutionary relationships among these species.

“For SK 15 to belong to P. robustus, it would imply that it is an extreme outlier of the species, differing both in size and morphology from the latter,” the researchers note.

This suggests that Paranthropus was more diverse than previously thought, with different species adapting to specific ecological pressures. Was P. capensis a failed experiment in hominin evolution, or did it leave a lasting genetic legacy? For now, the fossil record remains silent.

The discovery of P. capensis is a reminder that human evolution was not a straight-line march toward Homo sapiens. Instead, it was a tangled, branching tree, with many species emerging, flourishing, and ultimately fading away. The fact that P. capensis existed at all suggests that evolution was constantly experimenting with different adaptations, testing the limits of what it meant to be a hominin.

As new fossils continue to be discovered and technology improves, more species like P. capensis may emerge from the shadows of prehistory. Each one will add another puzzle piece to the story of our deep past, revealing a world far more diverse and complex than we ever imagined.

-

Zanolli et al. (2022). Enamel-dentine junction morphology and Paranthropus diversity in South Africa. Journal of Human Evolution. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2022.103542

-

Kupczik et al. (2019). Root and crown morphology of Paranthropus molars and their implications for diet. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2019.0532

-

Lee et al. (2023). The dietary adaptations of Paranthropus and their role in Pleistocene ecosystems. Quaternary Science Reviews. DOI: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2023.106721

-

Madupe et al. (2023). Proteomic analysis of Paranthropus enamel and implications for taxonomic diversity. Nature Communications. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-40982-1