Speaking was very risky during the fifty-four years long Asad family domination of the republic.[1] By speaking, I am not only referring to public speaking inside Syria. A private conversation between neighbours, a comment made to a colleague at work, or a public talk on a US campus, all could potentially be reported and documented. Reports could lead to all sorts of consequences: travel bans, arrests, torture, disappearance, or death.

A soul-crushing atmosphere of fear and suspicion weighed down on Syrians primarily, but also on the Lebanese and Palestinians who were once subjects of this brutal dynastic rule. It is hard to forget the palpable fear in my parents’ voices and demeanours when, as a thirteen-year-old, I uttered a few words against Hafez al-Asad at a hotel in Beirut known to be one of the hang-outs of Syrian secret service officers.

That said, some ended up speaking a lot, producing flows of discourse that glorified the wisdom of “our leader till eternity.” Between sycophantic speech and silence stood the courageous ones who before the 2011 revolution dared to speak truth to power and to name things by their name, paying a hefty price for their parrhesiastic speech.

In the first hours after Bashar al-Asad fled to Moscow, the dams blocking speech for decades, especially for those Syrians who remained inside the regime-controlled areas, began to crumble fast. The bad-faith self-debasement and inflation of the leader’s qualities also disappeared from the airwaves. They were replaced by a deep feeling of relief, of finally turning a page in the country’s history. The promise of new beginnings was accompanied by a collective effervescence laced with apprehension at what the future may bring.

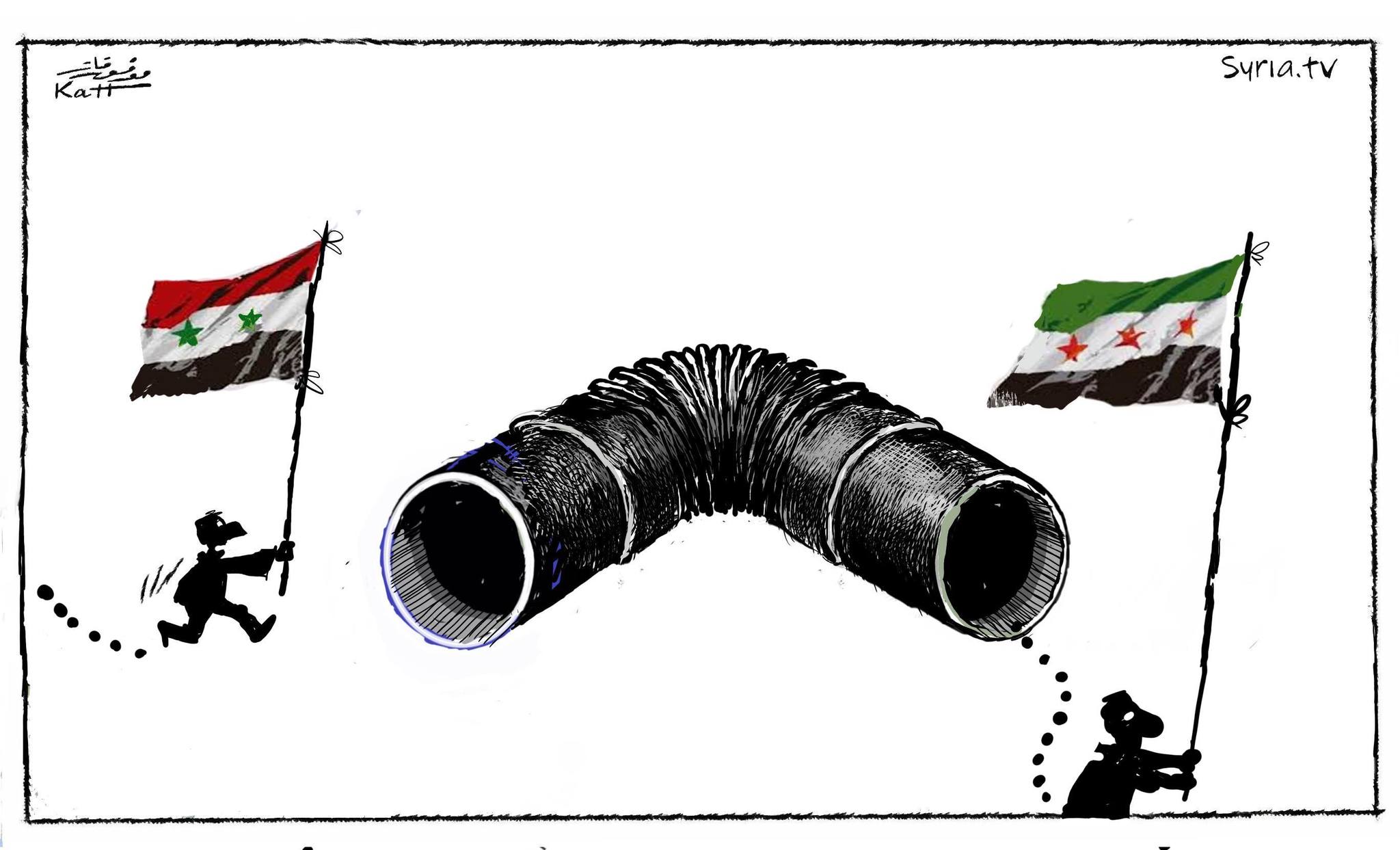

Amidst the proliferation of unrestrained public speech, on the streets, on social media, on satellite TV stations and on numerous podcasts, emerged a folk concept, which was deployed to calibrate some of the newly unbridled speech acts. Takwi’, which literally means taking a turn in Arabic, has been deployed to mean something closer to a volte-face. If a turn it is, then it is surely a U-turn. The concept spread like wildfire and was deployed to apprehend the sudden and public reversal of positions by former regime supporters from different social strata; ranging from ordinary citizens, who replaced the regime’s flag with the revolution’s flag on their social media accounts; to intellectual elites who were vocal in their support of Assad; and former members of the regime, who all of a sudden became critical—some even volunteering to air secrets behind its technologies of subjugation.

Motives for engaging in these speech acts are as varied as the different backgrounds of those engaging in them. The children of the Asad regime officials who spoke may be doing it out of a desire to escape potential revenge or incrimination as former prime benefactors, or to guarantee that their interests won’t be impacted in the future. Former media elites who kept singing the praises of Asad for years, forming part of an intellectual chorus that worked hard to preserve the regime’s legitimacy, may also be worried about the consequences of their past actions. Some may want to jump on the bandwagon, while others may find the interregnum the right moment to recycle themselves by indicting the former regime and whitewashing their past. While the motives for performing a volte-face are numerous and difficult to ascertain, what they all share is an intention to perform a historical recalibration that seeks to re-articulate the relationship of past to present during the interregnum.

Perpetrators, benefactors, and supporters of the former dynastic rule rush to convert themselves into bystanders, victims, and survivors.

The timing is crucial precisely because these speech acts are taking place in the interval before the crystallisation of historical narratives. Takwiʿ wedges itself between history-as-event and history-as-narrative-of-the-event. It is an attempt at seizing the moment of transition between the old and the new, when agents, particularly elites, but not exclusively so, seek to realign themselves by recasting their own previous positions. Perpetrators, benefactors, and supporters of the former dynastic rule rush to convert themselves into bystanders, victims, and survivors. Needless to say, these acts of public self-re-narration are generating a lot of discussion.

Unlike scholarly debates that call into question essentialist accounts of histories to underscore their socially constructed nature, public commentaries around these speech acts revolve around whether they are honest, truthful accounts or forgeries of the past. The stakes are high, because these narratives are tied directly to ethics, politics, and justice. For instance, some narratives, which re-calibrate the relationship of past to present may be seeking in one way or another to dodge responsibility and escape accountability.

Will accountability for past actions be sacrificed on the altar of forging a potentially inclusive future?

Recent elite volte-facers claim that they, too, were victims of the Asad regime and that, if they were not directly its victims, they too were survivors of the regime’s horrors. One could consider these new narratives, despite the whitewashing and potential forgeries, a call for fostering a new and inclusive political community; one that lets bygones be bygones. But in doing so, will accountability for past actions be sacrificed on the altar of forging a potentially inclusive future?

Even if elite volte-facers’ accounts are a mixed bag of honesty and whitewashing, what we are witnessing in the flood of social media posts, TV interviews, and podcasts, is the unequal distribution of the power to craft narratives about the past. Artists, former regime officials, and their progeny are given much air time to attempt to polish their tarnished reputations. Arab Satellite TV stations that host them may be furthering their own agenda for elite recycling. This is more than anything else a testimony to the fact that these volte-facers retained their names and their faces. For while they are busy offering words and tears on screens, hoping that their acts will buy them a new beginning, tens of thousands of Syrians remain disappeared. Their names were erased and replaced by numbers, and their bodies mutilated and piled up in mass graves. It is those, whose dignity was trampled on and whose speech was extinguished, who await a justice-to-come.

Featured image: This cartoon by the well-known Syrian cartoonist Mwafaq Katt was published on Syria TV and on his Facebook page on 15 Dec 2024.

[1] This essay was conceived in January and completed by the first days of February 2025. It is a commentary on the initial emergence of the folk concept of takwi’ in the days directly following December 8th, 2024.

Abstract: Takwi’ (to make a turn in Arabic) has been drawn on a lot to refer to former supporters of the Al-Asad regime who have abruptly reversed their positions. I will examine these volte-face narratives which reframe the past in, and for, the present, and the kinds of interventions they perform, in light of the Syrian intellectual debates about the relationship of violence, representation and dignity.