What historians of science do is social and cultural history, but of a sort that is sometimes harder to look at from the bigger picture.

(Historian of Soviet science Michael Gordin, in an interview with historian of East-Central European science Jan Surman 2016)

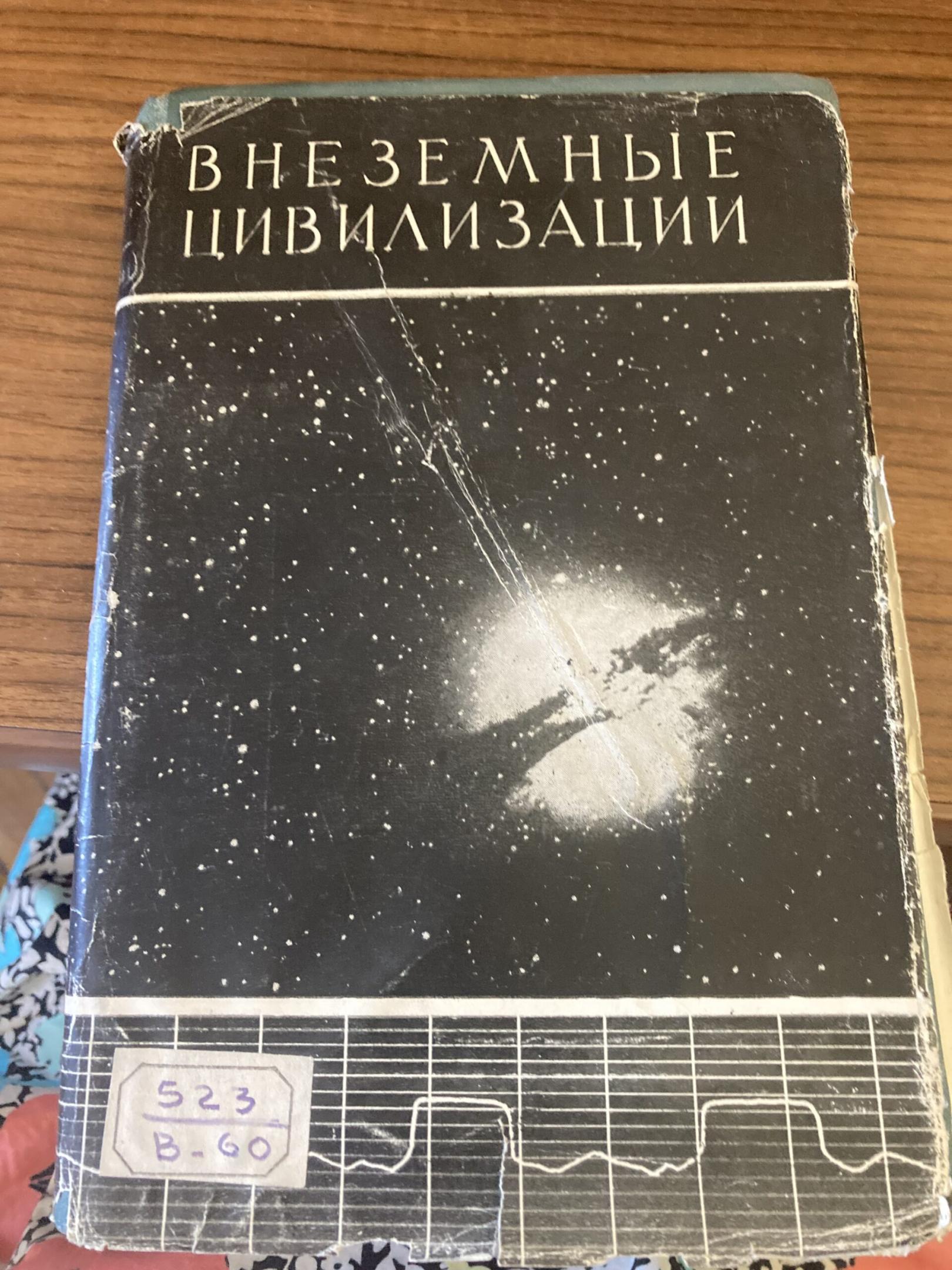

Upon submitting my MA dissertation in Social Anthropology on critiquing capitalism through different labor sites a decade ago, I stumbled upon a publication that strongly impacted my choice of research. Issued by NASA, it dealt with interstellar anthropology and the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) through astronomy. Much later, when looking for a PhD research in the history of science, I discovered a topic that enabled me to address how knowledge production about the Universe and human contact with other beings are intertwined with the social and the political in Soviet SETI, about which not much has been written.

Conducting my first oral history interview with a (though not Soviet) SETI anthropology pioneer taught me the value of memories and storytelling for my subject. My interviewee, Canadian Richard Lee’s life trajectory seemed like a perpetual, meaningful, and well-rounded journey of engaging with knowledge. Lee was not alien to SETI in the USSR. He had spoken at SETI’s most imposing Cold War event, the 1971 (first) Soviet-American Conference dedicated entirely to the subject, where over fifty scientists (from the US, Canada, the UK, and Hungary) participated. The conference took place at the periphery of the Soviet empire in Armenia. When, in a subsequent interview, SETI astronomer Iván Almár shared his experience as the only Hungarian representative on a highly international terminology committee working on a multilingual space dictionary, I started to ask myself what other nations have contributed to SETI and yet remain invisible or marginal. SETI’s requirement for highly powerful telescopes, subject to economic and political factors, limits scientists’ access and, more generally, human imagination in places disconnected from it. At least, this is how I saw it. By this time (2021), traveling to Russia to consult archives and conduct interviews was improbable due to the COVID-19 pandemic, so I adapted the timeline for additional field research in Armenia – another important location for my topic. I gained a scholarship to partially fund Russian language classes in Yerevan and dived into the mix of Soviet SETI and Russian over the summer of that same year. My focus shifted from the center to the periphery of the (former) Soviet Union.

What is SETI, and what does it have to do with Armenia? In the second part of the twentieth century, technologies capable of receiving and interpreting the non-visible part of the electromagnetic spectrum were developed. This led to a new type of astronomy called radio astronomy. A portion of this non-visible light – radio waves, specifically – had the potential to travel considerable distances, enabling unprecedented information on the Universe. In this context, extraterrestrial intelligence also became a scientifically legitimate pursuit that still endures. The idea that civilizations in the Universe could use radio waves to send signals to one another over interstellar distances fascinated radio astronomers. The USSR Academy of Sciences supported this new domain. It was near Yerevan, at the Byurakan Astrophysical Observatory (BAO), that Soviet scientists gathered for the “All-Soviet Conference on Extraterrestrial Civilizations and Communication with Them” in 1964. Moreover, extraterrestrial intelligence (or civilizations) generated an imaginary space at the intersection of science and politics. Iosif Shklovsky, the Soviet SETI pioneer number one, argued both in his book (1962) and at the conference (Tovmasyan, 1967) that civilizations tended to destroy themselves after a while when they reached the nuclear or communication stage. Scientists discussed a civilization’s chances of survival while pondering on radio signals of artificial origin. These signals were crucial – for launching and guiding extraterrestrial intelligent objects such as satellites, space probes, and intercontinental ballistic missiles (carrying nuclear weapons). Discussing SETI meant putting classified information on the table under the gaze of pure science. The success of the meeting – it moved the topic from a bottom-up initiative to an officially validated pursuit (the forming of a specialized section of the USSR Academy of Sciences to communicate with other intelligent beings) – allowed the first Soviet-American in 1971 in the same location. Yerevan, thus, played, at least for a while, a role in enabling the most prominent SETI meetings.

In reconstructing the legacy of the Soviet science-politics hybridity in the case of extraterrestrial intelligence and Armenia’s scientific intelligentsia, the driving research questions in my fieldwork asked: What kind of scientific-political relations between Soviet Russia and Soviet Armenia supported the act of gathering at BAO to discuss radio astronomy’s pursuit of extraterrestrial intelligence? What did the gathering reflect, and how did it resemble/ position itself to other phenomena at the intersection of science and politics in Russian-Armenian relations in which the scientific intelligentsia was embedded at the time? In other words, how can the historical reconstruction of the radio astronomers’ attempt to scientifically ground contact with extraterrestrial intelligence at BAO in Armenian space-time help understand some of the politicized societal and cultural conditions and experiences in this terrestrial space-time? As I ventured into the fieldwork, these questions sharpened up, and answers eluded me. This essay merely shows how the experience of reconstructing the history of SETI in Armenia led to seemingly barely tangent questions to the ones initially intended.

BAO had strong ties with Moscow. Moreover, the estimates are that generally, 40% of all enterprises in Soviet Armenia were devoted to defense (Curtis, 1995: 43; Bayadyan, private communication, 5 August 2021). Science had high political stakes in Armenia – both as an instrument in the hands of the Soviet central power, as well as an empowering tool in the hands of Armenians themselves, allowing them to advance their interests to Soviet central power, such as the official recognition of the 1915 Armenian genocide. Last, BAO’s founding director founder (1946-1988), astrophysicist Viktor Ambartsumian, was, according to Iván Almár, the most famous Soviet astronomer abroad. When, in 1964, a Moscow scientific-political elite of the USSR Academy of Sciences traveled all the way to Byurakan to listen to a few Russian-based scientists proposing SETI, they were convinced, not least by the presiding role of Viktor Ambartsumian of BAO backing of SETI. Khrushchev’s visit to BAO in 1961 made it the headline of the Soviet press. Such is the article [first image] in the Russian-language newspaper Kommunist, where a large picture shows Ambartsumian and the head of the Soviet state walking side by side at Byurakan. Generally, astronomy maintained itself at the top of the scientific-intellectual pyramid throughout the Cold War period in Soviet Armenia.

Contrary to BAO’s visibility, Armenian SETI not only seemed invisible among scholars in my field, but I could barely see traces of SETI at BAO overall. The library at BAO possessed only one reference document – the conference proceedings. In the tranquility reigning at BAO’s library, whose big windows face the rich foliage surrounding the building [Image 1], historiographical silence has set. Even though it hosted the two prestigious conferences, BAO never became involved in SETI research. Based in Mexico for decades, BAO’s main organizer, radio astronomer Hrant Tovmasyan, who was still living when I conducted my fieldwork, took the time to respond to all my emails and attest to this absence. Overall, Tovmasyan implied that there was not much going on regarding SETI at BAO. Once a leading figure in Armenian radio astronomy, space research, and organizing gatherings, Tovmasyan had even proposed a SETI experiment at BAO at the 1964 All-Soviet conference. Additionally, his shortness of memory contrasted with Lee’s proactive storytelling. Generally, there seemed to be much more pressing things to pursue than SETI in Armenia. This applied also to its history.

Today, radio antennas no longer exist at BAO. The observatory is a place of more importance for history than astronomy. Due to the economic and political decline that shattered the post-Soviet Armenian republic, the current technology is substantially lagging. What was once the most famous Soviet observatory abroad is now a beautiful relic of the past. On the premises of BAO, the house where Ambartsumian lived is preserved as a museum. Like the house, his office in the observatory’s main building is also a sacred room used only for meetings. Armenia altogether has also radically changed. Waves of economic decline started in the late Soviet era, including an armed conflict with Azerbaijan and a significant earthquake. They continued in the post-Soviet period, placing the development of science and technology and its very survival in the background of priorities. The preservation and reenactment of Byurakan’s legacy has since augmented, counteracting the scarcity of economic means. Terrestrial crises overshadow the pondering over universal ones.

Upon entering the fieldwork, it became clear that Armenia’s technical capabilities could not have allowed the pursuit of extraterrestrial intelligence in radio astronomy despite the impressive astronomical work at BAO. Historians and anthropologists I talked to in Armenia had prompted me on it. Radio astronomy simply did not amount to a large-scale activity. Although the small republic developed radio astronomy early on, its infrastructure, in this sense, did not compare itself with planetary radars – such as those in Crimea.

Even though Byurakan astronomers lacked the technical capabilities to search for and (attempt to) communicate with extraterrestrial intelligence, I have found that Armenian astronomers did not remain insensitive to the epistemology of the extraterrestrials. The name of Elma Parsamyan, the oldest employee of BAO currently, does not appear in the conference proceedings among the other Armenian scientists. However, no complete list of participants was given in the document – only a partial one listing profiles with political power and a list of presentations (with authors). The transcription of the discussions in the proceedings indicates additional actors’ presence. One of them was Paris Herouni (d. 2008). Elma Parsamyan and Paris Herouni shared a passion for archeoastronomy. Could archeoastronomy have anything to do with extraterrestrial civilizations in Soviet Armenia?

Parsamyan was at the conferences, it turned out. But she repeatedly refuses to talk about them, prompting me to think that some things were better kept secret. Instead, in our conversations, she repeatedly takes me through detours on her life as an astronomer, her love for Armenia, history, and the fraternity between countries in the Soviet Bloc. She makes countless references to the commonality between Romania (which she knows is my country of origin) and Armenia, based on a jointly perceived religious tradition – apostolic and orthodox branches of Christianity. It daunts me that perhaps talking about religion is another way of talking about BAO, judging by Parsamyan’s passionate verve. She emphasizes how science is important in Armenia and that Armenian scientists were patriots. She equates patriotism for Armenia with patriotism for Russia – “which has always been our friend.” She talks of her archeoastronomy studies in which she argued that Armenia had much older astronomical observatories than many other civilizations on Earth. I am mesmerized by how Parsamyan artfully avoided answering my questions.

Lee’s previous interview with his adventurous journeying through stories had given me the insight that a detour also leads to a meaningful answer. The epistemic confidence in pursuing extraterrestrial intelligence at the conference was very similar to that of Armenian astronomers (Parsamyan and Herouni) in the study of artificial ancient stone formations considered astronomical observatories on the territory of Armenia. BAO astronomers became increasingly interested in investigating and showing the ancient legacy of Armenian astronomy in the mid-1960s. This is also when Parsamyan, most prominently, became a voice in archeoastronomy and generally a time of national revival across all Soviet republics. The commonly shared Russian-Armenian extraterrestrial-terrestrial epistemology at the 1964 SETI conference can perhaps help understand the position of Soviet (Armenian) scientific intelligentsia (Antonyan, 2012) when Armenians went to the streets to ask Moscow for specific national claims. As a result, Armenians gained the right to commemorate the Armenian Genocide from 1915, which had been tabu for official Soviet policies seeking to have good relations with Turkey. Thus, Armenians successfully challenged an official Soviet policy affecting international relations. Could it be that by reinforcing national identity through ancient astronomical legacy, the privileged astronomical intelligentsia who could not protest in the streets with most of the Armenian population but whose sentiments resonated with it strengthened national identity through the ancient astronomical heritage?

For Armenian astronomy, deeply embedded in national and religious identity, the scarcity of recording and recalling the conference on extraterrestrial civilizations was not merely a question of deficit. It pointed to the presence of something else. Through her political acts on (extra)terrestrial civilizations, Parsamyan pushed the anthropological inquiry further into the hands of SETI history. In her last words, the Armenian astrophysicist candidly wished me to follow my passion and live an interesting life. It took me by surprise – Parsamyan, whom I had only associated with dealing with the past, had just pointed to the future.

Even when anthropologists have correlated past evidence with the present science of extraterrestrial intelligence and talked about the relations between culture and epistemology, religion, or employed feminist epistemologies and queer theories to gaze at SETI world-making, history has reproduced a hegemonic perspective of the West. The case of Soviet scientists who gathered at the Byurakan Astrophysical Observatory (BAO) at the height of the Cold War to discuss civilizations in the Universe challenges the hegemonic Western narrative of SETI. Highlighting Armenia’s role helps diversify the current historiographical discourse on science’s engagement with extraterrestrial intelligence and restore the historical record. Science’s engagement with extraterrestrial civilizations perhaps is not the same as (but broader than) the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI). In problematizing an epistemic object – namely, extraterrestrial intelligence – and seeing it as not only embedded in Soviet Armenian political conditions but as (part of) an active force that has influenced these political conditions, this essay destabilizes the Cold War bipolar (US vs. Soviet Union as equated with Russia, see Basalla, 2006; Dick, 1996) narrative of radio astronomy’s pursuit of extraterrestrial intelligence.

On the surface, no explicit trace of the conference(s) was left for a historical ethnography to investigate what transported extraterrestrial intelligence on Soviet Armenian premises and how this spoke for the Soviet Armenian-Russian scientific-political relations. The findings in the field challenged this deceiving appearance of a mere story of forgotten extraterrestrial intelligence that almost accidentally landed in Armenia during the Soviet era. Discursive detours unraveled the need to observe differently – to tune my vision just like radio astronomers tune their telescopic antennas in searching for information-rich signals. Performing detours is of the Earth. Even astronomers are forced to return to Earth if they are to detour. As an example, Parsamyan deployed her astronomical knowledge to ground Armenianness in precise terrestrial coordinates as a political action. A preconstructed inquiry frame was insufficient to capture this process, risking blinding the vision. Instead, locally-built tools became necessary to examine how science, politics, and society converged in Soviet Armenia. The current historiography of radio astronomy’s pursuit of extraterrestrial intelligence during the Cold War has only very recently focused on Soviet actors and so far remained silent on the role of Soviet Armenia. The effort to cover this gap and diversify the narrative by bringing in new actors and perspectives has just begun, including this article.

References:

Antonyan, Yulia. The Armenian Intelligentsia Today: Discourses of Self-Identification and Self-Perception. Laboratorium: Russian Review of Social Research, 4 No.1, 2012: 76–100. https://www.soclabo.org/index.php/laboratorium/article/view/279.

Basalla, George: Civilised Life in the Universe. Scientists on Intelligent Extraterrestrials. Oxford University Press, 2006.

Curtis, Glenn: Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. Country Studies, Washington D. C., Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, 1995.

Dick, Steven: The Biological Universe: The Twentieth-Century Extraterrestrial Life Debate and the Limits of Science. Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Gordin Michael, and Jan Surman. “Beyond the centre: Sciences in Central and Eastern Europe and their histories. An interview with Professor Michael Gordin conducted by Jan Surman”. Studia Historiae Scientarum 15 (2016): 433–452. doi.org/10.4467/23921749SHS.16.021.6164.

Tovmasyan, M. Hrant. Extraterrestrial Civilizations. Proceedings of the First All-Union Conference on Extraterrestrial Civilizations and Interstellar Communication. Byurakan, 20-23 May 1964. Jerusalem: Israel Program for Scientific Translations. 1967.

Abstract: In this essay, I emphasize the importance of detours in the fieldwork as an anthropologist who investigates history (of science). I recall the process by which an original research question on Armenian contributions to radio astronomy’s SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) during the Soviet era revealed subtle yet crucial historical context in which Armenian archeoastronomy studies emerged. Pursuing the original seeming impossibility of answering the original research question gave rise to detours, systematically. A deceiving appearance of a story of forgotten extraterrestrial intelligence that almost accidentally landed in Armenia during the Soviet era became something else as it unraveled the need to observe differently.