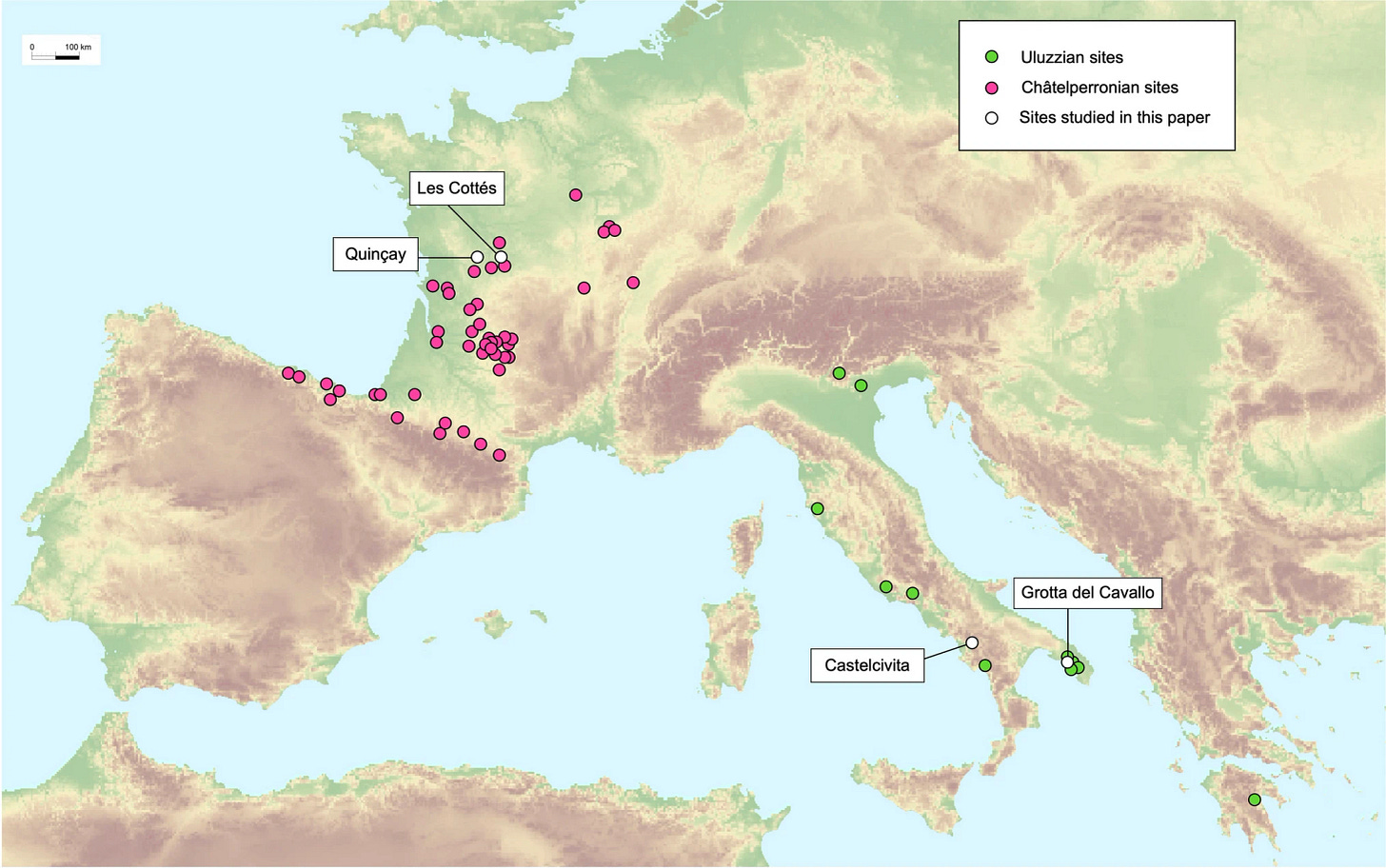

For decades, archaeologists have puzzled over a key moment in prehistory: the transition from the Middle to the Upper Paleolithic, a period marked by the gradual disappearance of Neanderthals and the spread of Homo sapiens across Europe. Central to this debate are two enigmatic stone tool industries, the Châtelperronian and the Uluzzian, both dating to roughly the same period—between 44,000 and 40,000 years ago. Found in different parts of Europe, these two industries have often been grouped together as “transitional industries,” implying that they might share a common technological or cultural origin.

But do they?

A new study published in the Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology has upended this assumption. By directly comparing the stone tools (lithics) of these two cultures for the first time, researchers have found no meaningful technological connection between them. Instead, their findings suggest that these two groups—one in France and Spain (Châtelperronian) and the other in Italy and Greece (Uluzzian)—were not just geographically separate but fundamentally different in how they made and used their tools.

The study, led by Giulia Marciani and colleagues, took an unprecedented approach. Until now, the Châtelperronian and Uluzzian industries had always been studied separately, often by researchers using different terminology and methodologies. To correct this, the team organized a workshop where archaeologists directly examined artifacts from both traditions side by side. The results were striking.

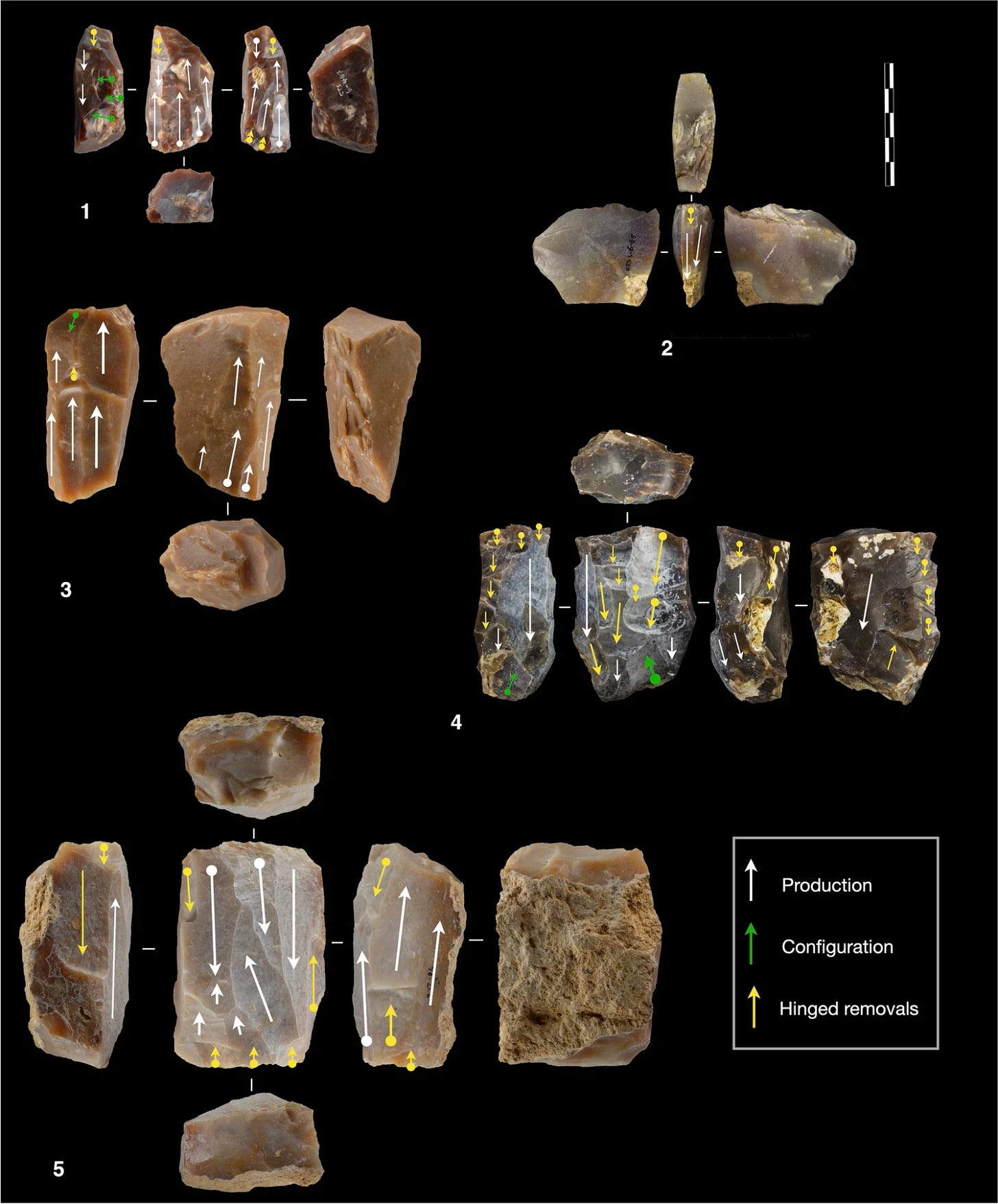

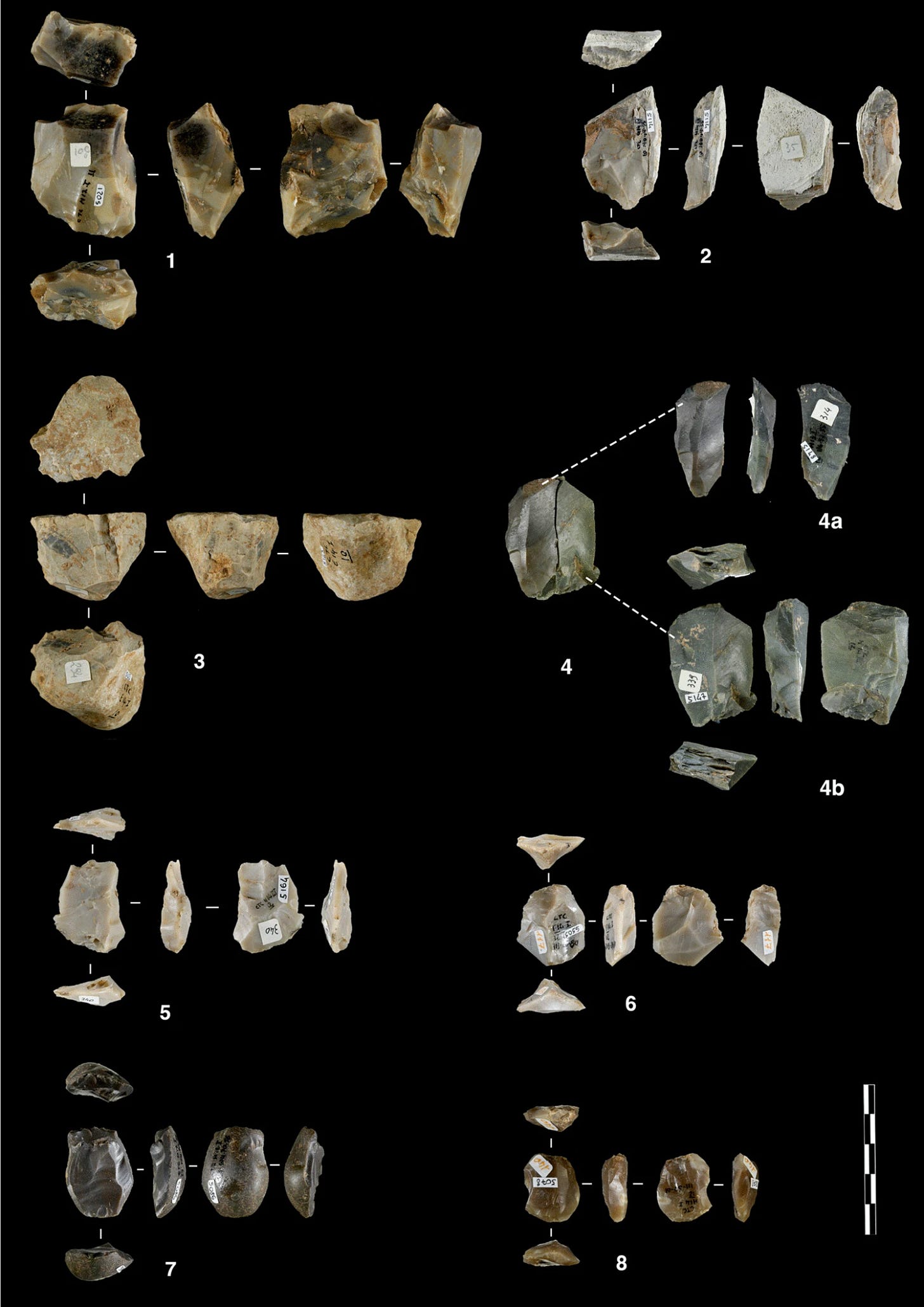

“Our analysis highlights significant technological divergences between these industries. The Châtelperronian is a blade industry with a minor bladelet component produced by freehand direct percussion, whereas the Uluzzian is a flake-bladelet industry with massive use of bipolar percussion.”

In other words, the Châtelperronian people—likely Neanderthals—crafted their tools by carefully striking long, thin blades from stone cores using controlled blows. In contrast, the Uluzzians—believed to be early Homo sapiens—relied heavily on a technique called bipolar percussion, in which a rock was placed on an anvil and struck from above, resulting in smaller, flake-like tools.

This fundamental difference in technique suggests that these groups did not learn from one another or share a common cultural tradition. Rather than representing a single “transitional” moment, these two industries reflect entirely separate traditions, developed in isolation from one another.

The identity of the artisans behind these stone tools has long been debated. Traditionally, the Châtelperronian industry has been linked to Neanderthals, largely because of skeletal remains found in association with these tools at sites like Saint-Césaire in France. However, recent discoveries have complicated this picture.

For example, at Grotte du Renne, a key Châtelperronian site, researchers recently identified a neonatal pelvis fragment that appears to belong to Homo sapiens rather than a Neanderthal. This has led some scholars to question whether Neanderthals really were the makers of these sophisticated blade tools—or whether early Homo sapiens had a hand in their production.

Meanwhile, the Uluzzian industry has long been associated with modern humans. Human teeth from Uluzzian layers at Grotta del Cavallo in Italy have been identified as Homo sapiens, reinforcing the idea that this tool tradition belonged to the first wave of modern humans entering Europe.

“Following the discoveries of Neanderthal remains in the Châtelperronian, the Uluzzian was also postulated to be a product of Neanderthals … However, recent morphometric analysis of teeth from Grotta del Cavallo confirmed that they belong to Homo sapiens.”

This finding is crucial, as it suggests that Neanderthals and modern humans did not necessarily share cultural or technological traditions, even when they lived in the same broad regions at the same time.

The study’s conclusions challenge long-held assumptions about how Neanderthals and modern humans interacted. If the Châtelperronian and Uluzzian industries were truly unrelated, then the transition to the Upper Paleolithic was not a single, unified process. Instead, different groups in different regions developed their own solutions to the challenges of survival—without necessarily influencing each other.

This has implications for how we view the spread of modern human culture. The Uluzzian industry, often seen as an early manifestation of Homo sapiens’ superior adaptability, appears to be a distinct tradition rather than part of a gradual blending with Neanderthal technology. The Châtelperronian, meanwhile, may not represent an attempt by Neanderthals to “catch up” with modern humans, as some have suggested, but rather an independent innovation that arose within Neanderthal communities.

“The distinctiveness of the Châtelperronian and Uluzzian highlights that technological behaviours in western Europe during the 45–40 ka period can be very diverse and that general labels such as ‘transitional industries’ are unsatisfactory in describing this diversity.”

As with any major study, these findings raise new questions. If the Châtelperronian and Uluzzian traditions were completely separate, what does this say about the interactions between Neanderthals and modern humans? Did they live alongside each other without exchanging ideas, or were their encounters too brief to leave lasting cultural traces?

And what about other so-called “transitional” industries across Eurasia? Were they also independent developments, or is there still evidence of cultural transmission between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens waiting to be uncovered?

Future research will need to examine other sites with the same side-by-side approach used in this study. Only by directly comparing artifacts across different regions and traditions can we begin to piece together the true story of how human culture evolved in the shadow of extinction.

For those interested in exploring this topic further, here are some key studies:

-

Higham, T., et al. (2024). Reevaluating the stratigraphic integrity of Grotta del Cavallo: New insights into Uluzzian chronology. DOI: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2024.107012

-

Djakovic, I., et al. (2022). Radiocarbon chronology of the Châtelperronian: A Bayesian approach. DOI: 10.1080/00310222.2022.2104378

-

Moroni, A., et al. (2018). Technological organization in the Uluzzian: Implications for the behavior of early Homo sapiens in Europe. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.06.004