When we think about human evolution, and cave men, we often imagine hunched-over or even knuckle-walking humans, reminiscent of our closest relatives the chimpanzees. It is understandable that one might think this, afterall, it has been part of our cultural zeitgeist for decades now. As protrayed in many depictions of man’s transition from “primitive ape” to our modern upright form, showcasing our sense of superiority and self-importance. Until relatively recently, it was thought by Anthropologists that this was in fact how our ancestors walked, as not only chimpanzees, but gorillas and orangutans also walk on their knuckles. The whole of the Great Apes move like this, with the exception of humans. Upon first glance, it would be almost silly to think our ancestors did not do the same, as evolutionary parsimony would suggest.

During my academic career, my primary research looked into the anatomical correlates between skeletal structures and movement types in primates. Specifically, I examined how certain features of the hip-bone, or illium, corresponded with movement types (or locomotor typologies). These classifications included terrestrial quadrupedal mokeys like baboons, the arboreal quadrpedlism of monkeys like macaques, the brachiation or arm-swinging seen in gibbons, prehensile tail hanging in many new-world primates, the knuckle-walking of the great apes, and the obligate bipedalism of humans. Here we tested how similar the hip bone was between the various groups to test the recent theory that humans never had a knuckle-walking ancestor, contrary to popular beliefe.

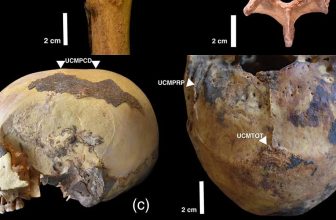

How can this be? Surely if all of our closest relatives walk on their knuckles, we must have as well! But to the contrary, all fossil evidence of human ancestry reflect upright bipedal locomotion. Even some of our oldest fossils, such as in Ardi, an Ardipithecus over 4 million years old, reflect a bipedal lifestyle in its foot and pelvic anatomy. Going back further, we see clear signs of bipedalism in our oldest ancestry such as Sahelanthropus. Dating back to 7 million years ago, roughly 1 million years after our divergence from the chimpanzee lineage, we see anatomical features that shows adaptations for bipedalism. The opening in the skull, or foramen magnum, where the spinal column connects, sat under the skull. This reflects the orientation of the spine to the head. In quadrupedal animals, the spine connects to the back of the skull, as it is oriented horizontally. But in humans and our upright ancestors, the spine is oriented vertically, holisng the head upright and centered above our legs which hold the body up.

In Sahelanthropus, the orientation of the spine, while human-like, is heavily debated. Some have concluded that while this species may have been bipedal, it was not obligatory and could move in other ways. It likely mixed its upright movement with its arboreal adaptations, as these first steps towards humanity were still among the trees.

Going back to my research, we found a close relationship in human hip features with that of the gibbon. Go find a video of a gibbon walking, and you may just see a modern-day relic of the precursor to human movement. In recent years their’s been an embrace of the idea that our recent ancestors never walked with their arms, and that we have, for a very long time, maintained the upright brachiation posture of the arboreal apes we descended from. Like the gibbon, when we left the trees we kept our upright posture, which freed our arms for gathering food, manipulating our environment, complex tool use.

What this also tells us is that chimpanzees, and likely even gorillas and orangutans, all descended from this gibbon-like ancestor, and all three of these species convergently evolved knuckle-walking locomotion. This may sound ridiculous, but when considering their larger sizes, the disposition to reverting to a form of quadrupedism seems more understandable. Further, all of these species can walk upright, fully bipedal, if they choose to do so. This possible bipedal ancestry is still evident in their behavior. The human lineage, once diverse and specious, bucked this trend and retained our upright posture, to our benefit as we became the most dominant species of our planet.