Written by Adeoluwa Chukwu

During an age where the flame of Pan-Africanism has been severely dimmed by the wave of neocolonialism, it is crucial to revisit the value of Pan-Africanism and why this ideology ought to be the future of African governance. It is necessary to engage in this analysis because many men, in particular, those of African descent, perhaps under the influence of a colonial education, economic view, religion, or propaganda in general, are inclined to doubt whether Pan-Africanism is anything better than intellectual tongue wrestling, earth-shattering speeches, and elaborate social theories. This view of Pan-Africanism appears to stem partly from a wrong conception of the purpose of African unity and partly from a wrong conception of the freedom that Pan-Africanism contemplates.

The United States of America could have been just a collection of countries instead of the immensely powerful federal union that it is today. Through federalism, however, the first thirteen colonies agreed to unite under one Federal Constitution, while the States submitting to it simultaneously maintained sovereignty, so long as its laws were not in violation of the Federal Constitution. Today, Africa is not federalized but it is just a collection of countries. Federalism must be understood as the uniting principal for African continental integration. If Pan-Africanism has any value at all for those other than political scientists, Afro-centrists, or social philosophers, it must be indirectly through the effect that a united African federal government, military, economy, and language would have upon the lives of every black person. It is in this effect, chiefly, that the value of Pan-Africanism is primarily sought.

Furthermore, if we are not to shrink in our endeavor to reveal the value of Pan-Africanism, we must first free our minds from a colonial view; free our minds from a colonial consciousness. A colonial consciousness, as I have invoked the word here, is a black person, i.e., a person of dominant African decent, who can only perceive the world through eyes of a white person; who cannot escape the psychological onslaught which colonialism imposes upon the minds of black people. An African of this kind is no African at all. He is integral to the success of imperialism and without him neocolonialism could not survive. He seeks to hold the offices occupied by the colonial authorities; to be the chief of the colonial police departments; to be the executive of colonial corporations. He seeks merely to switch positions with his oppressors rather than to build a nation of his own. This kind of African could never discern the value of Pan-Africanism because as a consequence of his severely colonized mind, he could never discern the value of himself.

Yet, these are the kinds of Africans that run the governments of African countries and that are installed in areas of government or public influence within the African diaspora. Pan-Africanism aims to integrate into one nation the entire black race on the continent of Africa and those among the diaspora. This objective aims to produce unity and a system of governance tailored to the cultural diversity of the black race. Now, it cannot be maintained that Pan-Africanism has had any very great measure of success in its attempts to produce these results. If you ask other races what benefit was gained from setting aside mere cultural and ethnic differences in order to unite, their answer would probably be “actual freedom.” But if you submit the same question to a Pan-African, he will, if he is candid, confess that his ideology has not been as successful at obtaining “actual freedom” for African people. It is true that this is partly accounted for by the fact that colonial powers have played a major role in limiting the manifestation of a Pan-African government through covert operations.

These operations typically involve assassinations of Revolutionary African leaders along with the corroboration of colonial minded Africans. Thus, to a great extent, the value that Pan-Africanism presents to African people has been clouded by those parties whose interests are negatively affected by it. With respect to colonialization, Pan-Africanism demands that all natural resources of Africa be removed from the possession of imperial powers and returned to the rightful owners of it. In this regard, Pan-Africanism threatens a serious injury to the western way of life. With respect to corrupt African politicians, Pan-Africanism requires upright government and leaders who champion honor, integrity, and justice before they champion financial advantages. For corrupt politicians then, Pan-Africanism threatens to rip a hole into their pockets. Because these forces have historically been in a position to exert their influence, whether by intimidation or by brute force, any Pan-African leader or movement which produced the smallest impression of success has either been significantly crippled or forcefully extinguished altogether. Pan-Africanism, because of the knowledge of its power to unearth the current order of the world, will continuously be met with aggression from colonial powers.

However, this is only part of the reality concerning the uncertainty of Pan-Africanism. Within the topic of Pan-Africanism, there has developed a kind of division which has forked into two different schools of thought. This, in my estimation, presents a threat to the future of the ideology and its overall value. On one hand, some Pan-Africans adopt the economic theories of socialism and communism within the traditions of western philosophers such as Marx, Engels, and Lenin. This school of Pan-Africanism is referred to as Pan-African Socialism. Under Pan-African Socialism, the problem of colonialism is not viewed through the lens of race, but instead it is viewed through the lens of “class.” The consequence of colonialism sprang from a desire for “profit.” In this greed for profit, according to Pan-African Socialism, the owners of the means of production exploited the labor of the workers for substantial profit. Out of this relationship between the owners of the means of production and the workers, emerged a hierarchy of class that is beneficial to the owners and alienating to the workers. The way to reconcile this problem, Pan-African Socialist argue, is that all natural resources and land of Africa should be owned by the State and the phenomenon of “private ownership” should be severely limited so as to eliminate the class hierarchies.

On the other hand, some Pan-Africans view the problem of colonialism through the lens of race. This school is referred to as Pan-African Nationalism. Under this school, colonialism is simply the consequence of being conquered by another race. The underlying problem of colonialism is not a class struggle, but it is race that is the driving force. It was race that determined whether a person was destined to be a slave, not what social class that person was associated with. No matter the practical skill or cleverness of a black person during classical colonialism, that skill or intelligence was of little, if any, relevance when it came to the determination of his social status. He was a slave because he was black, because he was an African, not because he was poor. A white man was free not because he was rich or skilled but because he was white. To eradicate the problem of colonialism then, the black race must behave similarly to the other races. The role that Pan-Africanism should play is uniting all black people into one Nation such as the UN has united the white race, regardless of one’s particular white ethnicity. For the Nationalist, it matters very little what corner of Europe one descended; what matters most is whiteness, not whether a white person is a German, a Frenchman, Englishman, or American. This simple truth for a Pan-African nationalist, is the foundation for all decisions regarding western interests. Thus, for the Pan-African Nationalist, the black race should also adopt a Nationalist approach and unite regardless of ethnicity but on the basis of race such as other nations. It is also true that this ideological split creates a heavy contradiction within Pan-Africanism.

First, the very ideological framework on which to base worldwide African unity has itself been torn asunder into two schools of thought by robust intellectualism and by philosophizing in circles. This divide between Socialism and Nationalism; Christianity and Islam; Republican and Democrat, undermines the value of Pan-Africanism by creating new channels of division. The value of Pan-Africanism resides in the diversity of black people; it resides in our cultural and spiritual differences. To observe the value that Pan-Africanism offers the black race, Africans must cease to divide themselves into factions, beyond the uniting element of blackness. That is not to say that they must fly from their myriad cultures and spiritual practices, but rather it is to suggest that none of these things ought to supersede the underlying element of blackness.

Second, the political ideologies of Socialism or Communism are frameworks conjured by European philosophers, many of whom were wholly complicit in the colonial exploitation of Africa. These ideologies were not conceptualized for the benefit of African people but instead for the benefit of poor white people who, at the time, were being oppressed by their own governments. To believe wholeheartedly that the philosophical frameworks designed by a culture that is responsible for colonization will produce liberation for its subjects is not at all practical. One of the values of Pan-Africanism is a renewed love for all things African; an intense respect for African cultural traditions and philosophy. It is here, I believe, where Africans should carve their own path to liberation; a path that is guided by their own, original wisdom; a path that follows the guidance of their ancestors and the literature of our own thinkers. Africans should not be persuaded too much by the wisdom of those who are outsiders.

Now, it would be remiss to discuss the value of Pan-Africanism without acknowledging the contributions the African Diaspora has made to the ideology in lieu of being separated from Africa as a consequence of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. Many political scientist support the idea that the ideology of Pan-Africanism was actually forged off the continent, among Africa’s scattered children. These Africans of the diaspora, enduring the brutal realities of slavery, found homage in the ideas of a united Africa. In particular, the Africans in the Americas and in the Caribbean such as Toussaint L ‘overture, Fredrick Douglass, Hubert Harrison, George Patmore, C.L.S. Lewis, and Marcus Garvey, to name a few, introduced modern perspectives on the ideology. Still, even before these men wrote on the issue, ancestors like David Walker in “Walker’s Appeal” or Martin Delaney, are also precursors to the idea of Pan-Africanism.

Of the giants of Pan-Africanism, no African has been able to unite more Africans under one flag (i.e., the red, black, and green) than the Honorable Marcus Garvey. Hitherto, no African has yet to build an organization that mirrors the magnitude of the United Negro Improvement Association (“UNIA”). The UNIA remains the most successful black organization in world history. It had one thousand divisions and claimed to have six million members in forty different countries. The pinnacle of this movement was Garvey’s attempt to begin an African shipping line, called the Black Star. This shipping company was intended to support the development of a system of commerce between the motherland and its diaspora. Till this day, the UNIA continues to be a model for what African Nationalism, Pan-African identity, and self-reliance looks like for African people. It is giants like Garvey that revealed to Africans the value of Pan-Africanism.

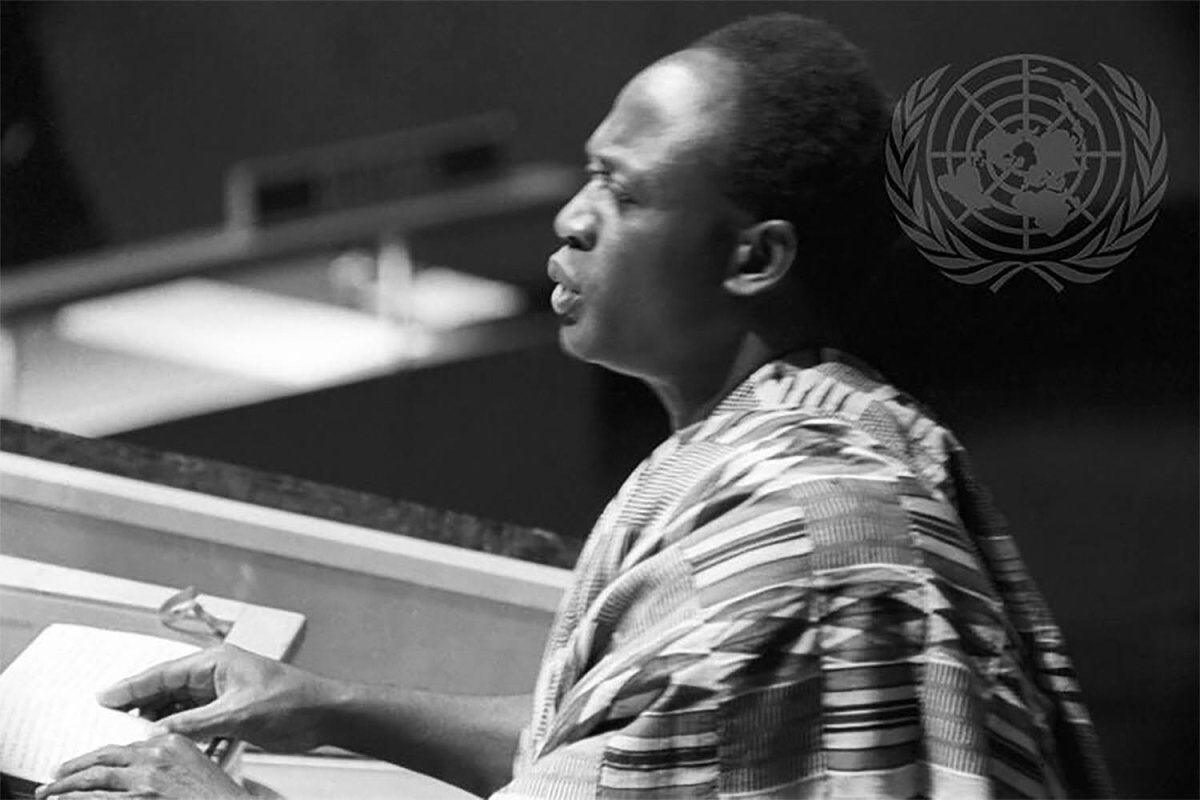

Moreover, whereas Garvey may be rightfully called the King of Pan-Africanism, the Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah may be rightfully called the High Priest of Pan-Africanism. Nkrumah is a perfect symbol for what Pan-Africanism represents. As a young man, he traveled to America in the 30s and 40s, when racism was at its height. He witnessed the discriminatory policies of America and the way these policies negatively affected the black population. Furthermore, Nkrumah attended Lincoln University, a Historically Black College or University. After Nkrumah’s stint in the US, he returned to Ghana where he would lead the revolution which ended in Ghana’s freedom from colonial control by England. Ghana’s independence, however, for Nkrumah, meant absolutely nothing if the entire continent of Africa was not also freed from colonial chains. He fought tirelessly his entire life to achieve the dream of a united Africa.

However, similar to the fate of other revolutionary leaders of the times, colonial manipulative strategies worked to turn Nkrumah’s Ghana against him, and he would eventually have to flee his mother country to escape a western sponsored coup d’etat. “All people of African descent,” Nkrumah famously reminded us, “whether they live in North or South America, the Caribbean, or in any part of the world are Africans and belong to the African nation.” Very few quotes from Pan-African leaders embody the principles of Pan-Africanism as these words from Nkrumah. The value of Pan-Africanism permeated the minds of African leaders back then, and it continues to do so today. In addition, after traveling to Africa and meeting with Kwame Nkrumah and other black leaders of the day, Malcolm X returned to America as a Pan-African more than he was a Muslim. It was in Africa that Malcolm X realized that respect and progress of African Americans was intricately woven with the respect and progress of Africa. Once Africa gained its liberation and complete independence, Malcolm X surmised, all black people in the world would ultimately have returned to them their human dignity. It is for these reasons when Malcolm X returned to America from his sabbatical in Africa, he broke away from the Nation of Islam and began his own organization that he called The Organization for African American Unity, modeling it after the Organization of African Unity. For Malcolm X, it is not just the Africans of North America that should be grouped under the umbrella of African American, but it is all Africans in the American hemisphere that are African Americans.

It is also worthy to note that it was not long after Malcolm X had made the ideological switch from mere African American Nationalism to Pan-African Nationalism that he was assassinated in Harlem by the aforementioned covert operations of the colonial regime. These monuments of men, such as Garvey, Nkrumah, and Malcolm X were inspired by the value of Pan-Africanism, and they gave their lives endeavoring to see that its principles were instituted. And while, no matter how close they may have come to the verge of the goal, we cannot say that they were successful. As a patriot of Pan-Africanism, however, I believe these ancestors were overwhelmingly successful in showing us the course to pursue, and that course ultimately is worldwide African Unity. It is in that golden phenomenon where the eternal value of Pan-Africanism is found.