Every so often, for the last few years at least, something comes across my feed about the death of cursive curricula in US public schools. The general tone ranges from it being a genuinely important part of United States Citizenship in being able to understand historic documents as primary sources, to…basically “kids these days.”

The latter argument is barely even worth responding to. You don’t get to strip something out of public education and then make fun of people for not knowing how to do it. It is 100% the fault of those who remove it, not those who didn’t learn it because they probably don’t really know it exists in the first place.

The former though…I can see that as being a legitimate thing, sort of.

I learned cursive in school, I wanna say we started in the fourth grade, but I could be misremembering there. I use it occasionally but really the only reason I write it now is to sign my name. Every so often I revisit my signature and see if I can make it look less like the work of a six-year-old. Having nice penmanship is impressive.

My aunt Pat and cousin Suzie write in the most amazingly beautiful script it makes it almost frustrating to think of how pitiful my own handwriting is. I practiced calligraphy for a bit, got pretty good, came up with a style of my own that I kind of liked writing. But then…I’m left handed and lightly puddled, wet ink is not really suitable for someone who writes left to right.

Having spent at least my fair share of time sitting in archives, I’ve gotta say…there’s not always a whole lot of mutual intelligibility there. Yeah, there are swooping, curly letters and upon immediately seeing it it’s pretty fancy. But letters were written differently, even if many period lesson books suggest otherwise.

Let’s look at a few examples, starting with the most straightforward.

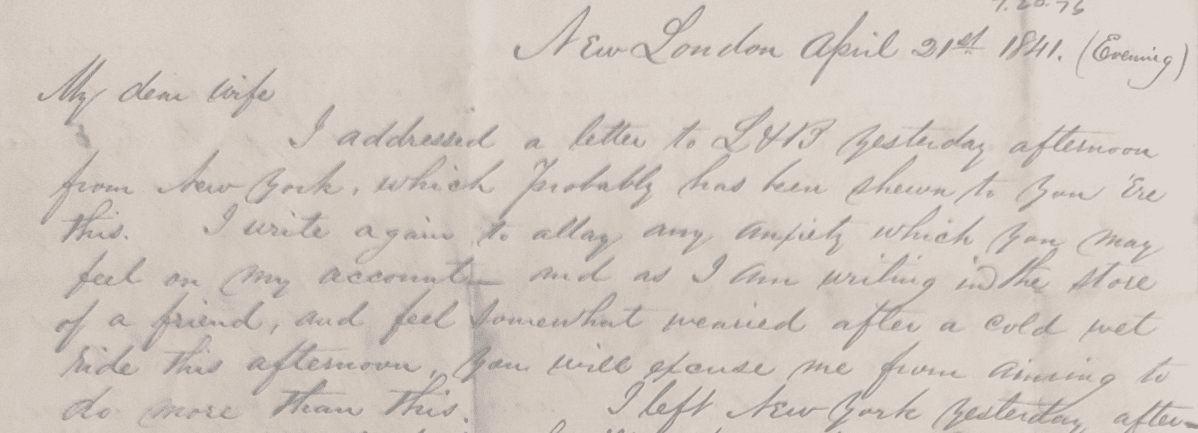

This is the start of a letter from Amos Chafee Barstow written to his wife, Emeline Mumford Eames Barstow, on April 21, 1841. Some of it is going to be immediately clear to you, some of it less so. There are only a few examples, like the lowercase p in April (and the word probably), which show significantly different letters. The word “‘ere” isn’t likely to be one that you see every day. This is one of many, many letters written by Amos Barstow which I scanned and transcribed for Lost & Foundry. Despite recognizing the writing and that it was English, it took me a bit to get good at reading Amos’s handwriting.

At this point I can recognize his relative age in his penmanship–he was 28 here–and it gets distinctly more shaky with more errors and cross outs as he gets older. At the end of his life it was growing quite poor. A solid understanding of cursive would probably get you through this one, though some of it might take a bit.

If you’re a cursive writer, I bet you have no problem at all reading this handwriting. This was written in 1901 by Grace Emeline Barstow, Amos Chafee Barstow, Sr.’s granddaughter. She is writing to her father (Amos Jr.) here. That pesky p is still a bit different but you might not have noticed it or maybe would’ve simply chalked it up to the writing of a 13 year old girl. That it may be, but we know from her grandfather’s handwriting that that ascender on the p is something that’s evolving out of handwriting by this point. Common in her grandfather’s time, it was shortening and almost feels mistaken by Grace’s time.

Now give this one a try. This is the start of a poem entitled “To My Absent Husband,” written in the 1840s by Emeline Barstow. It’s a long poem and she separated the page into two columns, which isn’t entirely apparent at first glance. Also, this isn’t really that poor of a photo–the ink is quite blurred. Some of this I’m sure you can make out. The rest…?

It took me a few hours to get through this entire poem and difficulty in transcribing aside, it’s heart breaking. Amos Barstow was well into his endeavor of starting what would go to become the Barstow Stove Company. He was spending most of his time either in the Norton, Massachusetts foundry or traveling New England to promote his business. Emeline was at home with two children and missing him.

Perhaps the most powerful line is when she describes their daughter’s excitement in thinking her father had come home, only to find out it was her mother. How that must have felt to the both of them is immediately relatable to parents–we’ve all had our kid pumped for one parent to come home only to find out it was the one who was there the whole time. That disappointment feels personal sometimes.

But how many of us reading this have had a spouse gone for sometimes weeks, with a handful of hastily written letters the only contact? The telephone didn’t exist yet. At the point this letter was written, the telegraph was a new fangled contraption. There was no communication except the occasional letter. Emeline’s pain is palpable and understandable.

So was mine in trying to transcribe this poem. It’s not just the font, either. Spelling has changed. Colloquial language use has changed. Do you know what quinsy is? I didn’t until I read yet another of the letters in the Barstow collection. I thought it was a misspelling or something I just couldn’t read correctly. I circulated the excerpt between friends, and one posted it in a group and someone in THAT group recognized it because they either have a medical background or are into that sort of history. Quinsy is essentially a tonsil abscess. I thought I was reading the word right but decided I couldn’t be. Turns out it was just antiquated language. That’s a huge part of reading this stuff, too.

Howbout earlier?

Here’s an example that should make you feel all warm and fuzzy if you’re from the United States. It’s a letter from George Washington to Jean-Francois de Chastellux , a French military officer assisting Washington during the American Revolution (courtesy of moutvernon.org). This is one dates back to 1784, and while you can probably make out a bit of it, it isn’t simple by any means to read this.

It’s probably a bit disorienting at first, if you’ve never read something like this. It (for me) starts off looking like a different language. Then I start picking out letters and realizing I should be able to understand this. Then more and more gets filled in and I start understanding individual words. Then I start looking for patterns in other words that I can’t read at first. Sometimes I scan and zoom in. Sometimes I try to rewrite the word to see how the shape of them fits into how I write.

After a while, sometimes pretty quickly, sometimes hours, sometimes days, my eye is trained and I can read a given individual’s handwriting and by extension have a pretty easy time reading similar handwriting. It does start with cursive, but it doesn’t end there. It’s not a matter of “ok kids, you’re 9 now, time to make things more difficult because that’s what I did.”

Cursive is important, but not simply because it may be what you learned. Things having been done before is just not a good enough reason to continue doing them. I don’t think we use sundials much in K-12 anymore, either. They do have their utility, though, albeit increasingly narrow.

As does cursive. In addition to looking pretty fancy, it is a gateway into reading and therefore understanding primary source documents. It’s a fascinating and under appreciated aspect of language–not just of the English language. I also know German, and learning to read Sütterlinschrift, poor though I was at it, was amazing.

Sütterlinschrift was the last commonly/widely used form of the script style Kurrent. I’m not nearly as practiced as I used to be, but being able to read it is way cooler than being able to talk to your friends in Pig Latin. The process of reading it is the same. I learned the individual letters, then in reading gobbledygook like this, I started picking out letters and then words I recognized. Those patterns help decipher others. As a starting point, the third to last word in this is “Gymnasium,” which is basically a kind of German high school.

So, learning antiquated writing systems and styles has its practical applications. But if we remove the “you should because I did” aspect, the only thing that’s really left is reading historical documents. Which is absolutely a reason to learn it. But. BUUUUUT. How many of us have read primary source documents that had not yet been read? Or transcribed?

Howbout I make it real easy. How many of us have not read primary source documents that haven’t already been studied extensively to the point you can base your academic career on the study of them? Probably most of us.

For the most part, the primary source documents most people are likely to be required to (or really have any inclination to) read are highly scrutinized and the contents of them is widely and immediately available, in a printed font. It isn’t necessary to learn cursive to be able to read the Declaration of Independence or the United States Constitution. It’s nice to be able to, sure. And I agree that part of English, Social Studies, or US History classes should include it.

But the whole thing here is that funding for public education is continuously stripped at the federal level. From 2010-2020, federal funding dropped from 12.5% to 7.5%. That’s considerable, and leaves progressively more and more funding to be picked up at the state level. This puts increasing pressure on states to fund public education and strains budgets overall.

Teachers are paid poorly overall, and classroom supplies often come out of their personal funds. Things that aren’t absolutely necessary start getting cut. Spending several weeks on an antiquated writing system that most people don’t need to know other than writing their name isn’t viewed as absolutely necessary. And….5% of a federal budget is a lot larger than 5% of a state budget. State funding in general has increased by 136% since 1977. While that sounds impressive at first, a lot of that was to compensate for federal cuts.

Music is often among the first to suffer…and compared to music, cursive doesn’t stand a chance.

I do have a point here, two of them, actually.

The first is that in its current state of use, cursive–though really cool–is absolutely not necessary. Just like the rotary phone, typewriter, phonograph, and Levallois–tools, skills, and technologies fade away as newer, more efficient, or simply more exciting methods come to be. Kids these days may never know what it’s like to suffer through hours and hours of “A, S, D, F. G, H. J, K, L, SEMI.” Kids these days also type 752 words per minute with two thumbs using swipe. It’s fine. It will be fine. We will come through this trying time of being reminded of our mortality.

Being that it isn’t necessary but has its real applications, we have two options:

The first, is to adequately fund public education to be able to include programs like this–at the federal level. I know, I know…it costs money to have a baseline public education. Personally its worth it to me to have highly educated peers in my community. But as educational funding grows, so to will the programs that were cut. Things like marching bands and extracurriculars and cursive start being within the scope of what schools can afford to staff for and focus on.

The second, is to accept that we don’t want public schools to funded to the extent that learning cursive or other tangentially important but otherwise obsolete skills are a given. In this case we continue or even increase our federal divestment while prioritizing the privatization of education and accepting that public education just isn’t a high priority nationwide, and that the state is the top level at which education should be addressed.

I’m…not a big fan of the second option. Having a baseline minimum education is something that’s incredibly important to me, and it’s also critical to maintaining the United States’ presence at the forefront of the global community. Cursive is not the key to United States Supremacy, but looking at it’s practical application not only gives us insight into why it may be fading from common use–it can serve as a window to understanding a bit about the “whys” of ongoing changes in the United States Public Education System.