By

Felix Stephens

BSc Global Humanitarian Studies

This is a fictional piece about an ethnographer attending the funeral of a famous writer. It explores the power of different mediums, how literature and anthropology deal with themes such as (im)mortality.

******

I was there for professional reasons, to carry out research as an ethnographer. Me, standing on the side, both feet on the moist shaved grass, a meter away or so from the crowd gathered on the gravel. Their hands were held together while the voice of a friend gave a eulogy directed at the man in the closed casket.

Although I’d gotten the approval of the family, I didn’t feel comfortable taking out my notepad and writing on it, not now. I’d decided to be attentive, try and remember what I saw and write everything down later. Hopefully after the ceremony, I could approach the people remaining and ask the few questions I had for editors, friends and family members. The thick air and the stillness of movements led me to meander mentally, unsure if these thoughts were of academic quality or simply personal observations.

The shape and the timelines of funerals seemed to follow the same blueprint. Gestures I’d seen repeated before, the personal act of accompanying someone to its last resting ground followed impersonal patterns. A cynic would have said it’s because there’s not much unique about our lives anyway. The man in the casket might have said there isn’t anything unique about our lives yes, our bodies, thoughts and actions all belong to history, but that the lack of uniqueness isn’t synonymous with lack of poignancy. Just look at those faces hiding in someone’s shoulder.

There was, of course, no way of knowing what he would have said because he was dead. For one, his words would have been better written. Mine are just speculations and that wasn’t why I was here. Fiction, as a writer, that had been his job.

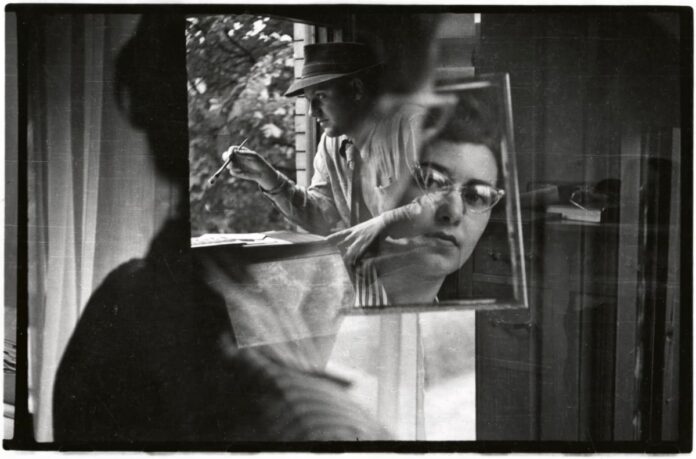

There wasn’t a lack of observations to write down. I’d been to funerals, as part of the active grieving audience, the differences between the intimate ones I knew, and this one were striking. Three distinct groups were laid out in a half-circle around the marble stele. The intimate ones, longing truly, some in tears, others holding those in tears. Another group, mostly men, wore impeccable suits and tried looking as solemn as possible. They were the editors, the professional audience whose duty, perhaps pride in being here, had led them to pay their last respects. The third group, to which I belonged, was very small. We were looking around, observing the audience and trying to grasp the appropriate moment for us to perform our work. We were journalists, photographers and me.

******

“The next life; Collective remembrance of fame after death”. She approved, ambiguously, and said “It’s a nice name for a research project, or for a book, it has a nice ring to it”. Amongst the soft-spoken voices and clattering of plates, now that we had changed rooms, I’d approached an elder family member, the aunt of the deceased writer. I only had a few questions for her and she seemed to have more for me. She asked if she could read my notes. I said she could and she stood there skimming through them for the next ten minutes. “I can see you’ve come to the same conclusions my uncle did”. I hadn’t properly formulated a conclusion for myself yet. “What do you mean?” I asked. “That our lives cease being our own work once were dead.

– I haven’t written that down.

She smiled faintly. The statement was brushed away and she leaned onto another observation. This time about the details I’d found time to write down between the end of the ceremony and the gathering. The expressions on people’s faces and the tone of their voices I’d tried to capture in words. “If you end up wanting to write about this interaction, in your research” she said, “please leave out those silly little details and retain only my words.” I’d wanted to ask why, but thought I’d just agree.

******

There seemed to be little I could convey about her and her truths, without those silly little details, as she had called them. It dawned on me, as I walked out, passed the stele which read “M.K”, that the same transformation had occurred when I tried to describe expressions and tones, as when the friend gave his eulogy. Someone’s identity suddenly became impersonal, in a thin third space, and in my case, to the service of my research. The man in the closed casket wrote books. His fiction was a way of searching without stealing, whilst impressions, mine particularly, stole and turned into fiction by trying to search.

I turned around and headed back to the gathering. The flapping of my notebook, the books I’ve read, the mechanics of fame, and how one’s life might live on according to some collective imagination were far gone. I thought about the elderly lady and wondered how she felt, in her own words, just so I could forget to write it down.