Article begins

A piercing alarm bell suddenly erupted, making a shiver run down my body. The noise came from the “barrier-free restroom” (无障碍卫生间) in front of me, presently occupied by my two wheelchair-using friends. They had just entered the restroom together ten minutes earlier while I waited outside for them. Behind me was a busy metro station passageway where commuters were passing by quickly, showing puzzled or annoyed expressions at the roaring noise, and then continuing to run to the security check to catch their trains. What happened? My mind went blank as the shrill from the bathroom continued to invade my thoughts. It lasted for several minutes before a middle-aged female janitor in uniform appeared, muttering and complaining, visibly displeased with the people who triggered the alarm in the washroom. The janitor took a key and opened the door from the outside. The two wheelchair-using women rolled out with frowns and, anticipating the janitor’s yet-to-be-uttered chastisement at what was a false alarm, they said that they had done nothing unusual and did not know how the push-button alarm was triggered.

This seemingly dramatic occurrence was ordinary in my fieldwork on urban accessibility in Shenzhen, a new mega Chinese city and global economic hub. My interlocutors, Jade and Star (anonymized), migrated from northern China to Shenzhen in 2023 after graduating from college, working as a team to build self-advocacy networks and manage social projects. They identified as members of a younger cohort of disability activists and their roles involved a lot of daily movement through the city’s public spaces—metro stations, theatres, community service centers, shopping malls, and bars. It was nothing new to them to encounter and deal with a “decapitated road” (断头路) in different senses of the term, much discussed within the wheelchair user community. The term refers to a wide spectrum of barriers of access for disabled people that includes dead ends with no ramps, locked toilets, and passers-by staring with pity or amusement during perplexing circumstances.

As we left the subway station that day, Star smiled bitterly, and Jade commented, “I don’t understand why the alarm was designed this way. It’s not an interactive intercom system. It doesn’t relay calls for help to the security guards or janitorial staff but just creates an annoying sound in the vicinity that transmits anxiety and unease to the people around it. Not to mention that there’s no instruction or indication next to the button. So, there’s no way to predict what’s going to happen until it’s pressed. Even if there is an emergency, what we need is not for whoever is outside to break in; Maybe we just want to call and get tampons. Also, ironically, why did the janitor come over with a complaint, as if we’ve done something wrong, and without thinking that being amidst the noise will only make it harder for us?”

The above circumstances and Jade and Star’s ensuing confrontation with the janitor raise some important questions: What was the source of this noise? Why do facilities for accessibility result in friction that could in turn be interpreted as noise? Who defines noise, how do people respond to and deal with disruptive noise? More importantly, how are noise and access connected?

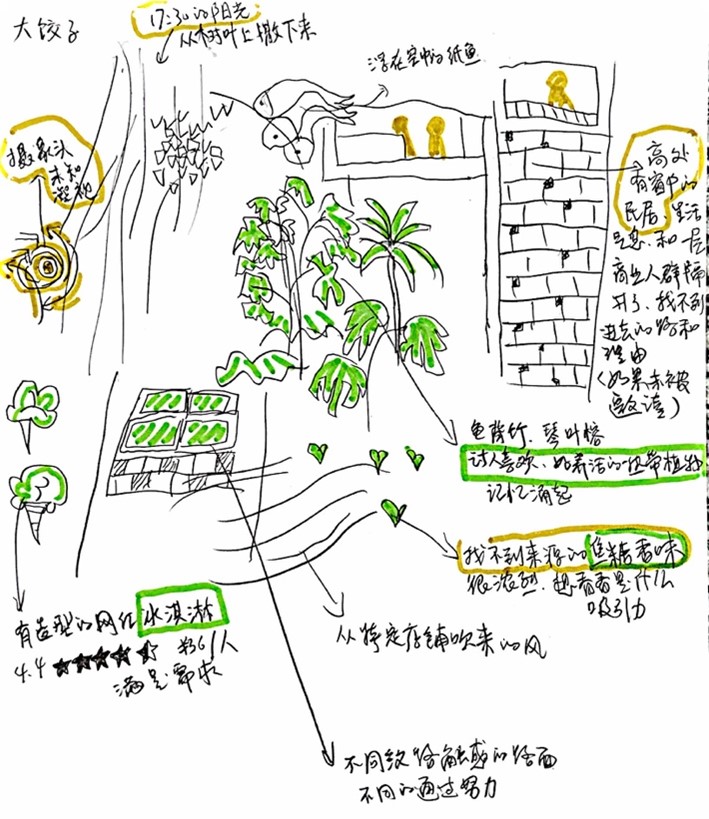

Credit:

Zihao Lin

Neighborhood in the quickly urbanizing Shenzhen where Jade and Star lived.

While infrastructure designers may assume that noise-based alarms provide necessary protection for disabled people trapped in confined spaces, this supposed protection is based on a one-sided imagining of the needs of people with disabilities. Furthermore, as Jade implied, such inattentive design and maintenance also lead to additional frictions which in turn reinforce the “burden” and “trouble” that people with disabilities allegedly cause.

Noisy alarms and their one-sided design transcend countries, highlighting questions of pervasive institutional ableism. For instance, in the autumn of 2022, while interning at an international organization in New York, I was also trapped in a wheelchair lift in an empty conference hall for nearly 10 minutes. When I realized that the lift’s doors could not be opened from the inside, I saw no other option but to press the red “Emergency Stop” button, and the same deafening alarm erupted, leaving me short of breath. The only emergency contact provided in the lift was the manufacturer’s hotline. The first reaction of the security personnel, who came late, was to request my credentials for security checking, ready to hold me to account for the noise and the hassle. Later, I learned that the facility management had set the lift to be operated from outside only, presupposing that all visitors in wheelchair do not travel independently and always have an assistant or attendant. The alarm, essentially, was a signal to the management rather than the trapped person in need—trouble had arisen!

In my research, “access” and “accessibility” are often ambiguous terms. State officials, non-disabled professionals, disability advocates, and corporate equipment vendors understand them differently. Many inaccessible “barrier-free” facilities—ramps that are too steep, alarms that scream but fail to communicate needs, accessible toilets set on the third floor—fulfil policy requirements on paper but do not respond to the bodily needs of people with disabilities. These inaccessible “barrier-free” facilities rather reinforce stereotypes and stigmas about disability. Noise and what gets interpreted as noise reveal the deep chasm between policy promises and community needs.

In response, I introduce the idea of “vital access” to describe the kind of access that people with disabilities create based on their own lived experiences and embodied necessities. Paying attention to vital access echoes scholars and activists in focusing on how people with disabilities disrupt inaccessible “barrier-free” projects imposed on them by non-disabled experts and how they create vital relationships and infrastructures that allow them to enjoy meaningful lives. “Vital” refers to both life-and-death matters and the recognition and pursuit of pleasure, sense of belonging, and desires, all of which are intertwined but overlooked in technical and legal discussions of accessibility. Sound plays a specific role in making and maintaining vital access. Cherry, a blind mother who has lived in Shenzhen for six years, says she has an outstanding “foot quotient” (脚商)—her witty recast of “intelligent quotient” (智商)—when walking through new places. For her, “any sound providing information is not noise.” When exploring the city, she likes the richness of the hustle and bustle (烟火气). The shouts of shopkeepers at the night market, the cries of children in the distance, and the plaintive cuckoos (八声杜鹃) whose melodious chirps only resound in the evening. They are all invitations to enter and enjoy a particular world.

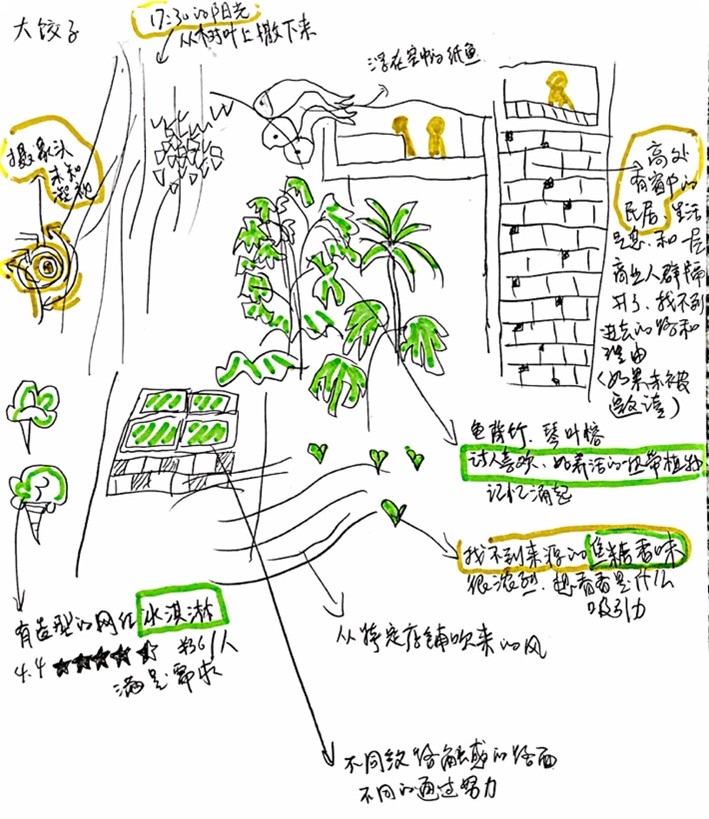

Credit:

Big Dumpling

A multisensory map: Jade and Star periodically organized city tours for people with disabilities and collectively created multi-sensory maps about the toured space.

To Cherry, the Shenzhen Metro is a place where information flow is cluttered, and she feels that amidst the chaotic flow of people, the sound of station announcements, and on-screen advertisements, one needs to concentrate to locate the station’s elevators and escalators. On rare occasions, there are audible cues set up at these points, but often there are simply none. Cherry locates an escalator by following the rustling sound of the belt rolling in the Metro station. She cringes at the grinding of the rusty rails while travelling in the train carriage, which interferes with her effort to discern station announcements and the voiceover from her cellphone when used on board the train. Sound is therefore a quintessential signal for enabling Cherry’s vital access.

Incidentally, people with disabilities also face situations where the question of sonic access to meet their vital needs is interpreted by others as noise. Cherry recalled that at one point there were audible traffic prompts installed at the intersection near the neighborhood where she lived. But it disappeared after a while. A friend of Cherry, Jade knew of this episode and shared that she had heard of many similar situations among the peers she supported, and that it was usually the neighborhood’s hearing residents who filed complaints against the audible prompts because of the “noise nuisance” (噪音扰民). In Jade’s opinion, the very fact that these audible traffic prompts were interpreted as a form of noise demonstrates a lack of public education about disability accommodation. Yet in Cherry’s case, the municipality acquiesced to such complaints because it got to make another budget for new silent traffic lights when updating street facilities.

Emerald, an assertive Deaf and sign language advocate, who had just used her savings to buy an old house near Shenzhen, had to deal with complaints from her downstairs neighbors from time to time about the noises she made in the middle of the night—toilet flushing and slamming of doors, or clapping and laughing with joy and excitement while signing. While Emerald did not care for these sounds, she respected her non-signing hearing neighbors’ sonic experiences. While Emerald used handwriting and text messages to maintain a passable relationship with her neighbors, Cherry, faced with the arbitrary appearance and disappearance of audible traffic prompts, was denied the opportunity to engage in dialogue at all. Whether it be the distant municipal unit allocating resources or hearing people complaining about noise nuisance, the needs and experiences of individuals with disabilities are overlooked in designing and maintaining sonic public infrastructures.

These moments are a reminder that access frictions are common in disabled lifeworlds, and that facing, rather than avoiding, these noisy conflicts create the vital relations that all people need to survive and thrive. As many disability activists observed, access is not a fixated entity, but a cyclical process of collective worldmaking. Star, Jade, Emerald, and Cherry supported each other as they recognized the shared experiences of coping with such frictions. Noise can be disruptive, but it can also be generative as it compels us to reflect on our psychosomatic needs and questions of how to create access for them. What is noise for one may be a constituent element of vital access for another.

Sanghamitra Das and Taylor Bell are the section contributing editors for the Society for Medical Anthropology.