Introduction

Private health service delivery is becoming increasingly dominant in biomedical landscapes worldwide. In global health circles, private health services are at once seen as a welcome contribution to the global push toward Universal Health Coverage, yet induce anxiety as an addition to the medical care landscape that remains little known, highly heterogeneous, and that operates largely beyond the gaze and influence of state and global health initiatives (see e.g., WHO 2020). The nebulous health markets are understood as teetering on the brink of market-oriented temptations to cut corners in health service delivery, compromising the quality of care and exploiting people’s health vulnerabilities to maximise profit.

In this cartoon by Arifur Rahman, a baby’s parents bring her to the doctor in a private health facility. “Doctor, our daughter has caught a cold, please give us some medicine,” the mother requests. “I will give medicine,” replied the doctor, “but before that, let’s get a urinalysis and x-ray from my lab.” (Source). Author’s archives.

Global health discourse positions state governance through regulation as the key to standardising health service delivery in the private sector and restraining private health actors from acting on less scrupulous inclinations. Hopes inscribed in regulatory discourses reflect a concern with social ordering. As anthropologist Sally Falk Moore wrote long ago, regulation appeals to “folk notions of social causality, on ideas of how to make things happen through the power of government” (Moore 1978: 7). Health governance discourses rely on the power of state institutional mechanisms for regulatory aspirations, hinging on nostalgic conceptualisations of institutions as virtuous (see the introduction to this thread) and separate from politics. In these, state mechanisms are imagined as holding the power to align health service enactments with global and national ideals.

In this contribution, I examine regulation as a bundle of social practices that emerge around maternal health markets in rural Bangladesh. Here, imaginaries of the state are not infused with ideas of virtuosity, and state institutions are widely seen not as transcending the ruling political regime but as extending it. Since the reinstatement of democracy in the country in 1991 until the summer of 2024, the country has swung between rule under two political regimes. The Awami League, headed by Sheikh Hasina, the daughter of the late Sheikh Mujib Rahman, the country’s first prime minister, formed one axis of this political pole. The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), headed by Khaleda Zia, wife of the late General Zia, who became president in 1975 following the Awami League coup overthrow and Sheikh Mujib’s assassination, formed the other. General Zia faced his own downfall in 1979, and the BNP was replaced by a military dictatorship until 1991. Since then, political power has contentiously bounced back and forth between these two parties, each taking advantage of their time in power to punish the other. These power games were dominated by the Awami League after they were voted into power in 2008. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina blocked the political participation of the BNP under her increasingly dictatorial rule. Discontent with her government’s leadership culminated in a student-led popular uprising through which she and her party were thrown out of power on 4 August 2024. The three decades of power tug-of-war preceding this have had far-reaching implications woven throughout everyday life, including for regulating health markets.

Cartoon image of Sheikh Hasina (left), leader of the Awami League party and Khaleda Zia, leader of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP). Author’s archives.

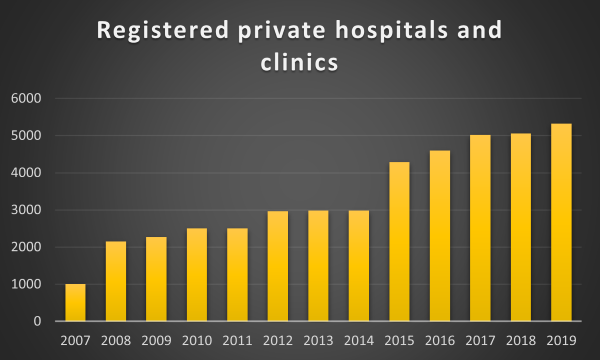

While the growth of private health service delivery is a global phenomenon, it has been particularly recent and rapid in Bangladesh, with registered hospitals and clinics growing five-fold between 2007 and 2019.

Number of formally registered beds in Bangladeshi private hospitals and clinics between 2007-2019; Source data: Government of Bangladesh, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOH&FW) Health Bulletins. Figure created by the author

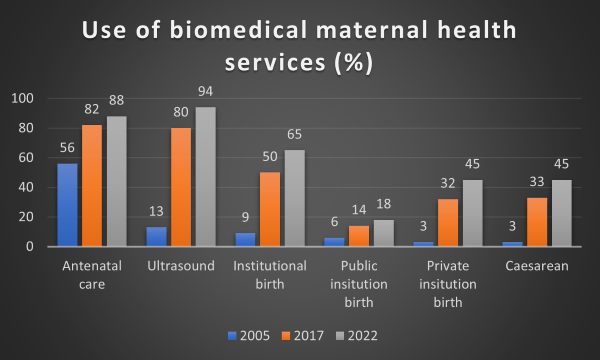

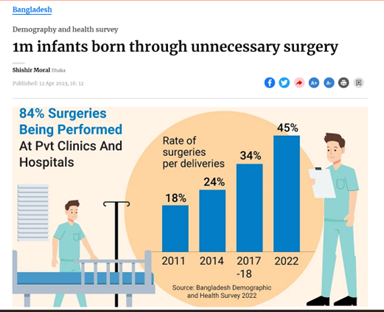

The shift toward privatisation of health care is particularly visible in relation to childbirth care. In only two decades, births in health facilities increased from fewer than 10% in 2004 to 65%. This shift has been primarily toward care-seeking in minimally regulated private health facilities, where over ‘80% of births are through caesarean1.

Use of biomedical health services during pregnancy and birth; Source data: Bangladesh Demographic and Health Surveys, 2005, 2007, 2022. Figure created by author.

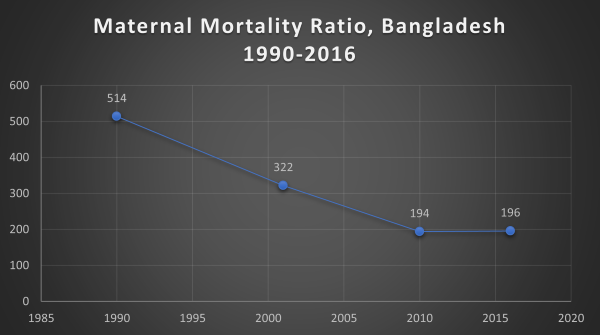

In tandem, the maternal mortality ratio stalled.

Maternal mortality ratio, Bangladesh 1990-2016; Source data: WHO estimates (1990), Bangladesh Maternal Mortality Surveys from 2001, 2010, and 2016. Figure created by author.

These trends provoked alarm in global and national health policy and programming circles. Here, actors often evoke regulation of private health services as the answer to what has been described as a caesarean “epidemic” (The Lancet 2018). In these discourses, regulation is often conceived as the pathway to regularising how and when these surgeries are performed, thereby averting “unnecessary” procedures .

Here, in contrast to regulatory aspirations, regulation emerges through social processes embedded in personal and political relationships to render visible a mirage of adherence to licensing standards largely disconnected from health service delivery.

This paper examines the enactments of private sector regulation in the everyday, localised practices in peri-urban and rural Kushtia district, located along the western border with India. Here, in contrast to regulatory aspirations, regulation emerges through social processes embedded in personal and political relationships to render visible a mirage of adherence to licensing standards largely disconnected from health service delivery. Rather than standardisation, these processes result in differentiation along the lines of political regimes. We will begin this examination with the story of Shojib (not his real name), a small clinic owner in a remote sub-district of Kushtia.

Shojib’s story

Shojib runs his clinic in the most remote sub-district in Kushtia. His was the first of several small clinics established in the vicinity. After completing a master’s degree in business in the mid-1990s, he tried and failed to secure a highly desired government job. With this disappointment, he tried his hand as an entrepreneur. He established a small medicine stall near the government sub-district hospital and several other businesses. In 2001, a newly minted government doctor was posted to thesub-district hospital. One day, he approached Shojib and said, “You, my friend, give me a clinic, and I will do the clinic work.” Shojib pooled resources from a contracting business and established the clinic, composed of one operating theatre and a couple of recovery rooms where the young doctor conducted basic surgeries, the most common of which were—and continue to be—caesarean procedures.

“Ceasarean room” similar to the one at Shojib’s clinic. Photo by author, Kushtia Bangladesh, December 12, 2019.

In its early years, the clinic ran unlicensed. At that time, the BNP was in power. As a BNP supporter, Shojib was cocooned by his political party affiliation and unencumbered by the stipulations of state regulatory mechanisms. During this time, he did not think about the police, or what he may need to pay to stay in business. However, in 2006, a caretaker government took over state power in the country to pave the way for free and fair elections. With this shift, Shojib was compelled to license his clinic through formal institutional mechanisms. “I was supposed to get a license [before],” he explained. “However, my party was in power then, so I did not do anything at that time.” With the caretaker government in power, he no longer had this luxury. The police could come at any time and cause problems, he told me.

Shojib instructed the doctor to arrange papers to submit to the authorities. The doctor used his network of friends to arrange papers—documents that could show that the clinic met the requirements, regardless of whether or not it did. Shojib took these papers to the home of the civil surgeon, the government district health manager. Though the civil surgeon was posted to Kushtia, his personal home was located several hours away in a different district, and Shojib decided to visit him there. Shojib described him as a religious man who had visited Mecca to perform hajj and regularly prays. Still, according to Shojib, the man “eats a lot, he eats bribes (ghush khay).” Here, he appealed to idioms of eating and the “politics of the belly” common in other contexts, insinuating corruption and, specifically, the elite getting fat on the spoils of the masses (Biruk 2018, 116; Bayart 1993).

Shojib gave the papers to the civil surgeon and talked with him. Later, the civil surgeon’s secretary informed him that the civil surgeon wanted 30,000 taka (£260) to visit the clinic to finish the job. Shojib did not protest, as he perceived that this money was required for the civil surgeon to “see the right way.” Although the clinic did not employ formally trained health practitioners, Shojib had to show that three doctors and six nurses were employed by the clinic full-time according to licencing requirements—a fanciful expectation for a rural clinic whose core business involved stripping services down to the bone to place them within reach of the poor. Shojib and the young doctor arranged for people to come to the clinic during the visit to appear as clinic staff. The civil surgeon then completed the paperwork. Shojib recognises the distance between the licensing requirements and how he navigates regulatory loops to keep his practice running, but he shrugs this off. “This is the system,” Shojib says. “You have to do your business, right?”

His experience brings into relief the distance between the imaginaries inscribed in the idea of state institutions and their regulatory power to reshape the materialities and practices of care, and the ways regulatory practices emerge as social practices.

The years since have been challenging. After the Awami League victory in 2008, the scrutiny Shojib faced in regulatory practices ramped up. His safe cocoon of party loyalty had morphed into crosshairs. Private clinics, diagnostic centres, and pharmacies mushroomed along the street. Just outside Shojib’s clinic’s doors are two other clinics. All provide the same services, carried out by the same doctors who rotate between them. The digitalisation of licensing, introduced in 2019, rendered more complicated how Shojib needs to “show” the staff affiliated with the facility. Both formal and ghush payments have increase, especially the latter, given his party affiliation. Rather than reshaping how health services are delivered, regulatory practices have been enacted in parallel to service delivery. Indeed, as in other rural clinics, at Shojib’s, health services are still principally provided by informally trained staff and rotating doctors, and the entire business is built on caesarean procedures without clear-cut clinical justification. For him, regulation is a social performance decoupled from the provision of health services. His experience brings into relief the distance between the imaginaries inscribed in the idea of state institutions and their regulatory power to reshape the materialities and practices of care, and the ways regulatory practices emerge as social practices.

Rendering adherence visible through social and political practices

While regulation through licensing is imagined by global and national health policymakers and programmers as ensuring the standardisation of clinical services, Shojib’s account elucidates regulatory practices as a sinuous conglomeration of social processes that hinge on rendering visible a mirage of adherence. He emphasises the idea of “seeing”: In regulatory social practices, seeing is little about materiality; rather, it demands aligning the seeing of different actors to render visible a mirage of adherence.

As Shojib’s story highlights, social practices to ensure that clinics are “seen the right way” are tethered to personal and political relationships. Clinic owners draw from personal relationships to facilitate licensing processes. This explains why, instead of visiting the civil surgeon at his nearby office, Shojib travelled hours to visit his home. He viewed this as necessary to nurture this relationship and ensure the civil surgeon would “see” his clinic in the “right way”.

Such practices map onto longstanding social practices across South Asia, where opportunities and resources are accessed by leveraging personal social relationships, often referred to as patronage or clientelism. While such practices often take on a negative moral valence in international discourses, scholars have shown that patronage in South Asian politics is part of a moral universe rooted in mutuality and constitutive of social bonds (Piliavsky 2014). However, there is a great deal of ambiguity between that which is considered moral leveraging of social bonds to access resources and opportunities (Perkins 2023) and that which is considered immoral. Under the Awami League regime, people incrementally felt squeezed out from those benefiting from such practices. These practices became increasingly viewed as immoral and ultimately culminated in the student and popular uprising in 2024.

While formal regulatory frameworks are malleable for clinic owners as they can creatively “show” they are in adherence, political party affiliation often circumscribes the limits of this flexibility. Staying in business has been a delicate, tenuous political experiment.

Yet, as Shojib’s story illustrates, patronage-related practices were central to regulatory social processes in Kushtia well before the authoritarian Awami League regime. The success or failure to achieve licensing hinged on clinic owners’ ability to appeal to personal relationships with those in power or to nurture these relationships. In the absence of such personal relationships, it was oftenthrough what people refer to as ghush (bribes) that these relationships were lubricated, and the “seeing” of health officials brought into alignment. Shojib felt the weight of this increased scrutiny of being on the wrong side of party politics. He described increased hoops to jump through to remain in business. Under the Awami League regime, he was not alone in these vulnerabilities. BNP-affiliated ownersregularly described additional hurdles or having to pander to local politicians and their family members.

While regulatory discourses tend to presume state institutions that transcend partisan politics, in Kushtia, political party alignment has arbitrated how and the extent to which owners nurture and leverage personal and political relationships to achieve licensing. Shojib is not alone in basing his licensing navigation on the ruling regime. Regime alliance has long been a powerful mediator of how ownersmanage private health facilities. While formal regulatory frameworks are malleable for clinic owners as they can creatively “show” they are in adherence, political party affiliation often circumscribes the limits of this flexibility. Staying in business has been a delicate, tenuous political experiment.

Conclusion

Global health and national discourses related to regulating health markets are inscribed with the aspiration of state governance as a mechanism to order the social world, spatially standardise health service delivery, and curb what is described as the unjustified rise in caesarean rates. However, these aspirations turn on ideas of the virtuousness of institutions that are belied by imaginaries of the state in many spaces, including Bangladesh. In Kushtia’s minimally regulated health markets, localised enactments of regulatory social processes emerge as disconnected from these aspirations. These everyday practices reveal health service regulation as primarily political and social-relational exercises that remain both disconnected from national regulatory aspirations and peripheral to the creative enactment required to make biomedical maternal health technologies work in practice. These ultimately have contributed to differentiation along party lines rather than regularisation of health service delivery.

The student and popular movement that led to the fall of the Awami League in July 2024 was driven by discontent with the party, but also by fatigue with political patronage that has dominated the country since the restoration of democracy in 1991. The interim government is emphasising the need to build institutions decoupled from political regimes, imagined as crucial to moving beyond political patronage. It remains to be seen how this will reshape the social processes that constitute regulatory practices in the private health sector.

Featured image: Created using Chat GPT

Notes

References

Bayart, Jean-François. 1993. The State in Africa: The Politics of the Belly. (No Title). Cambridge; Malden, Mass: Polity.

Biruk, Crystal. 2018. Cooking Data: Culture and Politics in an African Research World. Duke University Press.

MOLLR. 1982. The Medical Practice and Private Clinics and Laboratories (Regulation) Ordinance 1982. edited by Ministry of Law and Land Reforms. Dhaka.

Moore, Sally Falk. 1978. Law as Process: An Anthropological Approach. London: Routledge & K. Paul.

Perkins, Janet E. 2023. “‘You Have to Do Some Dhora-Dhori’: Achieving Medical Maternal Health Expectations through Trust as Social Practice in Bangladesh.” Journal of the British Academy 11: 31-48 doi:https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/011s6.031.

Piliavsky, Anastasia. 2014. “Introduction.” In Patronage as Politics in South Asia, edited by Anastasia Piliavsky. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rahman, Ahmed Ehsanur, Janet Perkins, Aniqa Tasnim Hossain, Goutom Banik, Sabrina Jabeen, Steve Wall, and Shams El Arifeen. 2022. “Unpacking Caesarean in Rural Bangladesh: Who, What, When and Where.” Birth doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12636.

Rahman, Redwanur. 2007. “The State, the Private Health Care Sector and Regulation in Bangladesh.” Asia Pacific Journal of Public Administration 29 (2): 191-206 doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23276665.2007.10779334.

The Lancet. 2018. “Stemming the Global Caesarean Section Epidemic.” doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32394-8.

WHO. 2020. Engaging the Private Health Service Delivery Sector through Governance in Mixed Health Systems: Strategy Report of the Who Advisory Group on the Governance of the Private Sector for Universal Health Coverage. World Health Organization (Geneva: World Health Organization). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240018327.

Funding statement

This work was made possible thanks to funding awarded under the ESRC Postdoctoral Research Scheme of UKRI Research and Innovation (Grant number ES/Y010299/1)

Abstract: Private health service delivery is becoming increasingly dominant in biomedical landscapes worldwide. Global health discourse positions state governance through regulation as the key to standardising health service delivery in the private sector and restraining private health actors from acting on less scrupulous inclinations. In this contribution, I examine regulation as a bundle of social practices that emerge around maternal health markets in peri-urban and rural Bangladesh, where health marketisation has been particularly recent and rapid. Here, imaginaries of the state are not infused with ideas of virtuosity, and state institutions are widely seen not as transcending the ruling political regime but as extending it. In everyday practice, and in contrast to regulatory aspirations, regulation emerges through social processes embedded in personal and political relationships to render visible a mirage of adherence to licensing standards largely disconnected from health service delivery. These everyday practices reveal health service regulation as primarily political and social-relational exercises that remain disconnected from national regulatory aspirations and peripheral to the creative enactment required to make biomedical maternal health technologies work in practice. These ultimately have contributed to differentiation along party lines rather than regularisation of health service delivery.